Brahms’ German Requiem

MACA Classics Series

Friday 25 & Saturday 26 June 2021, 7:30pm

Perth Concert Hall

West Australian Symphony Orchestra respectfully acknowledges the Traditional Owners, Custodians and Elders of the Indigenous Nations across Western Australia and on whose Lands we work.

Brahms’ German Requiem

Johannes BRAHMS Ein deutsches Requiem (75 mins)

I. Selig sind, die da Leid tragen

II. Denn alles Fleisch, es ist wie Gras

III. Herr, lehre doch mich

IV. Wie lieblich sind deine Wohnungen

V. Ihr habt nun Traurigkeit

VI. Denn wir haben hier keine bleibende Statt

VII. Selig sind die Toten

Please note that there will not be an interval in this evening’s performance.

Asher Fisch conductor

Elena Perroni soprano

Adrian Tamburini baritone

WASO Chorus

Asher Fisch appears courtesy of Wesfarmers Arts.

Wesfarmers Arts Pre-concert Talk

Find out more about the music in the concert with this week’s speaker, Margaret Pride. The Pre-concert Talk will take place at 6.45pm in the Terrace Level Foyer.

Wesfarmers Arts Meet the Artists

Join WASO’s Principal Conductor, Asher Fisch for a post-concert interview.

This will take place immediately following the Friday evening performance in the Terrace Level Foyer.

Listen to WASO

This performance is recorded for broadcast on ABC Classic. For further details visit abc.net.au/classic

Asher Fisch introduces Brahms' German Requiem

WASO On Stage

VIOLIN

Emma McGrath^

Guest Concertmaster

Riley Skevington

Assoc Concertmaster

Semra Lee-Smith

Assistant Concertmaster

Graeme Norris

Principal 1st Violin

Zak Rowntree*

Principal 2nd Violin

Kylie Liang

Assoc Principal 2nd Violin

Sarah Blackman

Stephanie Dean

Amy Furfaro^

Rebecca Glorie

Beth Hebert

William Huxtable^

Alexandra Isted

Sunmi Jung

Christina Katsimbardis

Ellie Lawrence

Sera Lee^

Andrea Mendham^

Akiko Miyazawa

Lucas O’Brien

Melanie Pearn

Louise Sandercock

Jolanta Schenk

Jane Serrangeli

Bao Di Tang

Cerys Tooby

Teresa Vinci^

David Yeh

VIOLA

Daniel Schmitt

Kierstan Arkleysmith

Nik Babic

Benjamin Caddy

Alison Hall

Rachael Kirk

Mirjana Kojic^

Allan McLean

Elliot O’Brien

Katherine Potter^

Helen Tuckey

CELLO

Rod McGrath

• Tokyo Gas

Eve Silver*

Melinda Forsythe^

Peter Grayling^

Shigeru Komatsu

Oliver McAslan

Nicholas Metcalfe

Fotis Skordas

Tim South

DOUBLE BASS

Andrew Sinclair*

John Keene

Louise Elaerts

Rob Nairn^

Christine Reitzenstein

Andrew Tait

Mark Tooby

FLUTE

Andrew Nicholson

• Anonymous

Mary-Anne Blades

• Anonymous

PICCOLO

Michael Waye

• Pamela & Josh Pitt

OBOE

Annabelle Farid°

COR ANGLAIS

Leanne Glover

• Sam & Leanne Walsh

CLARINET

Allan Meyer

Lorna Cook

BASSOON

Jane Kircher-Lindner

Adam Mikulicz

CONTRABASSOON

Chloe Turner

• Stelios Jewellers

HORN

★ Margaret & Rod Marston

David Evans

Robert Gladstones

Principal 3rd Horn

Julia Brooke

Francesco Lo Surdo

TRUMPET

Jenna Smith

Peter Miller

TROMBONE

Joshua Davis

• Dr Ken Evans & Dr Glenda Campbell-Evans

Liam O’Malley

BASS TROMBONE

Philip Holdsworth

TUBA

Cameron Brook

• Peter & Jean Stokes

TIMPANI

Alex Timcke

HARP

Yi-Yun Loei^

ORGAN

Alessandro Pittorino^

KEY

Principal

Associate Principal

Assistant Principal

Contract Musicians˚

Guest Musicians^

★ Section partnered by

• Chair partnered by

* Instruments used by these musicians are on loan from Janet Holmes à Court AC.

About the Artists

Asher Fisch

Principal Conductor & Artistic Adviser

A renowned conductor in both the operatic and symphonic worlds, Asher Fisch is especially celebrated for his interpretative command of core German and Italian repertoire of the Romantic and post-Romantic era. He conducts a wide variety of repertoire from Gluck to contemporary works by living composers. Since 2014, Asher Fisch has been the Principal Conductor and Artistic Adviser of the West Australian Symphony Orchestra (WASO). His former posts include Principal Guest Conductor of the Seattle Opera (2007- 2013), Music Director of the New Israeli Opera (1998-2008), and Music Director of the Wiener Volksoper (1995-2000).

After returning to conduct the Boston Symphony Orchestra at Tanglewood and the Cleveland Orchestra at the Blossom Festival in August, highlights of Asher Fisch’s 2019-20 season include concerts with the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra and the orchestra of the Teatro Comunale di Bologne. Guest opera engagements include Fidelio and Adriana Lecouvrer at the Teatro Comunale di Bologne, Carmen, Die Zauberflöte, and Parsifal at the Bayerische Staatsoper, Ariadne auf Naxos with the Bayerische Staatsoper at the Hong Kong Arts Festival, and Pagliacci and Schitz at the Israeli Opera.

Highlights of Asher Fisch’s 2018-19 season included guest engagements with the Düsseldorf Philharmonic, Sydney Symphony and Teatro Massimo Orchestra in Palermo. Guest opera engagements included Il Trovatore, Otello, Die Fliegende Holländer, and Andrea Chénier at the Bayerische Staatsoper, Arabella and Hansel und Gretel at the Semperoper Dresden, Tannhäuser at the Tokyo National Theater, and Cristof Loy’s new production of Capriccio at the Teatro Real in Madrid.

Born in Israel, Fisch began his conducting career as Daniel Barenboim’s assistant and kappellmeister at the Berlin Staatsoper. He has built his versatile repertoire at the major opera houses such as the Metropolitan Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, San Francisco Opera, Teatro alla Scala, Royal Opera House at Covent Garden and Semperoper Dresden. Fisch is also a regular guest conductor at leading American symphony orchestras including those of Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, New York, and Philadelphia. In Europe he has appeared at the Berlin Philharmonic, Munich Philharmonic, London Symphony Orchestra, Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, and the Orchestre National de France, among others.

Asher Fisch’s recent recordings include Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, recorded live with WASO and featuring Stuart Skelton and Gun-Brit Barkmin. Widely acclaimed, it won Limelight Magazine’s Opera Recording of the Year in 2019. Fisch’s recording of Ravel’s L’heure espagnole with the Munich Radio Orchestra also won Limelight Magazine’s Opera Recording of the Year in 2017. In 2018 Fisch and WASO recorded Bruckner’s Symphony No.8 for WASOLive! and Stuart Skelton’s first solo album for ABC Classics. In 2015, he recorded the complete Brahms symphonies live with WASO for ABC Classics. Asher Fisch’s recording of Wagner’s Ring Cycle with the Seattle Opera was released on the Avie label in 2014 and his first Ring Cycle recording, with the State Opera of South Australia, was released by Melba Recordings.

Asher Fisch appears courtesy of Wesfarmers Arts.

About the Artists

Elena Perroni

Soprano

Praised for her “velvet soprano voice” (Philadelphia Inquirer), Elena Perroni has gained recognition on the international stage. Hailing from Western Australia, Perroni has made regular appearances with the Philadelphia Orchestra in title roles such as Iolanta (Iolanta, Tchikovsky), Rusalka (Rusalka, Dvorak), Tatyana, (Eugene Onegin, Tchaikovsky) and as Berlioz’s Les Nuits d’ete. Perroni made her opera debut with Opera Philadelphia in Charlie Parker’s Yardbird (Schnyder). As Doris Parker, she performed in the first opera to be performed at the legendary Apollo Theatre in New York City before reprising the role at English National Opera in 2017. Debuting in her home country as Mimi (La Boheme, Puccini) with the West Australian Opera in 2018 she then returned the following year as Violetta Valéry in Verdi’s La Traviata. She is the first Australian opera graduate of one of the most prestigious institutes of music, Curtis Institute of Music, where she graduated with the Festorazzi Scholarship for most promising vocalist.

Adrian Tamburini

Bass-Baritone

Adrian has enjoyed a long and varied career as an opera singer, concert performer, music educator, director and producer. In 2017, Adrian was the winner of Australia’s prestigious singing award, the Australian Opera Awards (YMF, MOST). His singing has featured on cinema releases of opera, international recordings, motion picture soundtracks, radio and television. Since his debut in 1997 he has had a varied career as an operatic soloist (Opera Australia, West Australian Opera, Melbourne Opera, Lost and Found Opera), a concert performer (Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, Zelman Symphony Orchestra, West Australian Symphony Orchestra, Canberra Symphony Orchestra). Over the past few years he has focused on sharing his passion for music by teaching singing and piano to the next generation of musicians. Adrian has had the privilege of working with renowned international conductors and directors and most recently performed in the world premiere of Luke Styles’ symphonic song cycle, No Friend But the Mountains based on the book of the same name by Behrouz Boochani which is to be aired on ABC television this month. In 2021 Adrian is proud to make his debut in productions by Pinchgut Opera and National Opera.

WASO Chorus

The WASO Chorus was formed in 1988 and consists of around 100 volunteer choristers who represent the finest form of community music making, bringing together singers from all walks of life. They regularly feature in the WASO annual concert season, and are directed by Andrew Foote.

The Chorus has built an international reputation for its high standards and diverse range of repertoire. While its main role is to perform with the West Australian Symphony Orchestra, the Chorus also maintains a profile of solo concerts, tours and community engagements.

The Chorus sings with the finest conductors and soloists including Asher Fisch, Simone Young, Stephen Layton and Paul Daniel. Recent highlights have included Poulenc’s Stabat Mater, Mahler’s Second Symphony and Verdi’s Requiem. In 2019 the Chorus performed at the Denmark Festival of Voice and in 2018 toured China with performances of Orff’s Carmina burana.

Andrew Foote

Chorus Director

Lea Hayward

Accompanist

SOPRANO

Lisa Barrett

Elyse Belford-Thomas

Anna Börner

Annie Burke

Alinta Carroll

Jesse Chester-Browne

Penelope Colgan

Caitlin Collom

Clara Connor

Charmaine de Witt

Ceridwen Dumergue

Fay Edwards

Bronwyn Elliott

Davina Farinola

Marion Funke

Kath Goodman

Lesley Goodwin

Ro Gorell

Diane Hawkins

Sue Hingston

Deborah Jackson-

Porteous

Michelle John

Bonnie Keynes

Brooke McKnight

Sheila Price

Jane Royle

Lucy Sheppard

Gosia Slawomirski

Kate Sugars

Carol Unkovich

Alicia Walter

Margo Warburton

ALTO

Marian Agombar

Janet Baxter

Llewela Benn

Patsy Brown

Sue Coleson

Jeanette Collins

Catherine Dunn

Kaye Fairbairn

Jenny Fay

Susanna Fleck

Dianne Graves

Louise Hayes

Katie Hunt

Jill Jones

Mathilda Joubert

Kate Lewis

Diana MacCallum

Robyn Main

Tina McDonald

Lynne Naylor

Philomena Nulsen

Deborah Pearson

Deborah Piesse

Fiona Robson

Neb Ryland

Rebecca Sheil

Louise Sutton

Olga Ward

Moira Westmore

Jacquie Wright

TENOR

David Collings

Nick Fielding

Matthew Flood

Allan Griffiths

Julian Jones

John Murphy

Andrew Paterson

Jay Reso

Chris Ryland

Simon Taylor

Arthur Tideswell

Stephen Turley

Malcolm Vernon

Brad Wake

BASS

Justin Audcent

Michael Berkeley-Hill

Charlie Bond

Bertel Bulten

Ken Gasmier

Benjamin Lee

Andrew Lynch

Tony Marrion

Peter Ormond

Jim Rhoads

Mark Richardson

Steve Sherwood

Chris Smith

Tim Strahan

Robert Turnbull

Mark Wiklund

Andrew Wong

About the Music

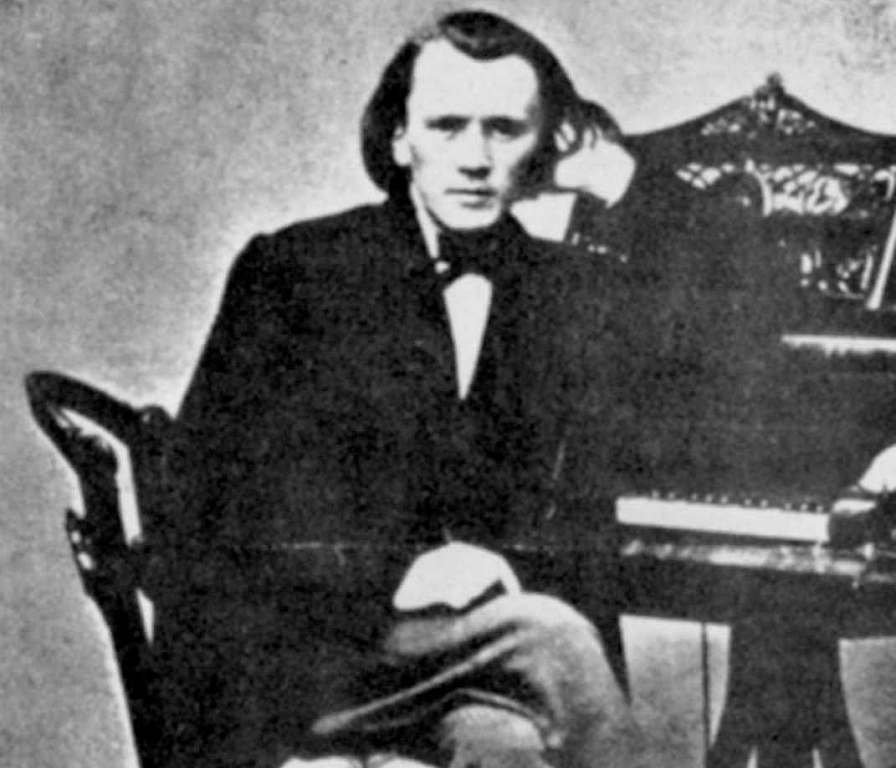

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

Ein deutsches Requiem (A German Requiem)

I. Selig sind, die da Leid tragen (Matthew 5:4;

Psalm 126:5,6)

II. Denn alles Fleisch, es ist wie Gras (1 Peter

1:24; James 5:7; 1 Peter 1:25; Isaiah 35:10)

III. Herr, lehre doch mich (Psalm 39:5-8:

Wisdom 3:1)

IV. Wie lieblich sind deine Wohnungen (Psalm

84:2, 3, 5)

V. Ihr habt nun Traurigkeit (John 16:22;

Ecclesiasticus 51:35; Isaiah 66:13)

VI. Denn wir haben hier keine bleibende Statt

(Hebrews 13:14, 1 Corinthians 15:51-2, 54-5;

Revelation 4: 11)

VII. Selig sind die Toten (Revelation 14:13)

A German Requiem, Brahms’ greatest choral work, is also one of his most personal and revealing compositions. First performed

officially in Bremen Cathedral on Good Friday 1868, it quickly won general acceptance throughout Germany and even further afield. Brahms had ‘arrived’ as a major composer. From then on he was to consolidate his position in public esteem, to the point where none, perhaps, of the great 19th-century composers had such widespread fame and so high a reputation in his own lifetime (except possibly Mendelssohn). Brahms’ fame was already established before he had written any symphonies (his first came out in 1876), and the success of A German Requiem reminds us of the importance of oratorio and choral/orchestral music in 19th-century musicmaking.

The Requiem is Brahms’ largest treatment of man’s attitude to death, a subject which preoccupied him throughout his adult life. Here, more than anywhere else, he lets us see his metaphysical, even religious outlook. As his first venture into large choral forms, the Requiem also shows how thoroughly this largely self-taught composer had steeped himself in the music of the past, emerging as a conservative master of choral idioms.

Tracing the genesis of A German Requiem can begin with its title: ‘A German Requiem, on words from Holy Scripture’. Brahms uses the name Requiem only in a very general sense; this is no liturgical requiem, and has no connection with the forms of worship of any church. Brahms calls it A German Requiem because the words are in German, not because he intended to write especially German music. Brahms chose the words himself from Luther’s translation of the Bible, showing that he knew it well. He had been brought up a Protestant, but lost his faith early, and was not a Christian believer. His admirer Dvořák once exclaimed: ‘Such a great man, such a great soul! And he believes in nothing!’

In spite of this, Brahms’ spiritual life was guided and formed by Biblical perspectives on life and death. The texts which spoke to him most strongly were those counselling contemplation, resignation and patience in the face of death. His thought is mainly pessimistic, but it is a pessimism shot through with gleams of hope – not the Christian hope of redemption and resurrection, but the achievement, through resignation, of eternal bliss. Brahms was deeply sensitive to the meaning of the texts he chose for the Requiem, and it is no accident that Christ is nowhere mentioned in them. Whereas the Catholic requiem mass is concerned at length with what happens after death and the day of judgement, for Brahms the last trumpet (or rather, in German, the last trombone) heralds not judgement, but the resurrection of the last day.

This is as far as Brahms goes, in the Requiem, towards the Christian message of hope. Elsewhere he is concerned mainly with consoling the living, those who have to stay behind, facing bereavement and their own inescapable death. There is no entreaty, no prayer for mercy.

Brahms’ friends quipped that he was happiest when he could sing ‘My joy is in the grave.’ The note he strikes at the beginning and end of the Requiem dominates it: ‘Blessed are they that mourn’ and ‘Blessed are the dead’. Brahms denied that his Requiem applied to any individual; he had the whole of humanity in mind. Nevertheless his own losses counted for much as he shaped the work. In 1856 his friend and mentor Robert Schumann died. The young Brahms had admired him to the point of hero-worship, and it was under the impact of Schumann’s death that he took up the rejected slow movement of the D minor piano concerto (No.1) and reworked it as the dark and implacable saraband which begins the second movement of the Requiem, to the words ‘For all flesh is as grass’. Then in 1865 Brahms’ beloved mother died. He was deeply upset, but this loss can only have contributed an intensification of feeling to a work already well in progress.

The Requiem was completed in the summer of 1866 while Brahms was staying in Switzerland. At this stage, it consisted of six movements only, predominantly dark in colour, and with a single soloist: a baritone. An initial performance in Vienna in 1867 was a failure – it was under-rehearsed, and the scoring was revealed as unsatisfactory, especially in the third movement. Brahms retouched these problem areas before conducting the official first performance in Bremen Cathedral. The baritone was Brahms’ friend Julius Stockhausen, who evidently gave an inspired account of the solo part; choir and orchestra were magnificently prepared, and the result was a triumph.

Brahms seems to have felt that something was still lacking in the overall balance of the work, in spite of the lyrical relief provided by the ‘How lovely are your dwellings’ movement. He added the soprano solo with chorus which, with its explicit reference to the mother comforting her child, is conceived as a memorial to Brahms’ own mother. In this form the work was performed at Leipzig in February 1869, where it had a cold reception. Leipzig – stronghold of the Mendelssohn faction – remained alone in Germany in failing to appreciate the German Requiem.

Brahms can be described as a Protestant composer in spite of his lack of any admitted religiosity. (As conductor of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde Choir in Vienna from 1870, he impartially presented Catholic and Protestant church music, concerned only with the intrinsic quality of the music.) His Protestantism appears both in his choice of Biblical texts and in the musical ancestry of his style. When he came to write choral music to German words, the influence of J.S. Bach was paramount. The appearance from 1850 onwards of the annual volumes of the complete edition of Bach’s works was a more important artistic stimulus for Brahms than any other musical event of his time. Brahms claimed that the four-movement cantata he had written around the ‘All flesh is as grass’ movement (the original core of his Requiem) was based on a

Bach chorale. Another influence was the music of the 17th-century German composer Heinrich Schütz. Brahms may have known Schütz’s serene Funeral Music, which has some texts in common with his own Requiem.

Brahms’ deep knowledge of the music of the past served to give discipline and form to the Romantic impulses in his musical style. The richness of A German Requiem lies in ardent Romantic feeling being poured into traditional forms. Unlike Brahms’ unaccompanied motets, his Requiem makes no parade of his contrapuntal learning, and he confines himself throughout to a single choir in four parts only. Generally speaking, when he resorts to fugal writing in this work, it is superbly apt, even in the passage which ends the third movement. This has often been criticised for excessive severity, but it contains a powerful piece of musical symbolism: just as the souls of the righteous are described in the text as being held in the hand of God, so the two separate but concurrent fugues, one in the choir, one in the orchestra, are held together by the mighty D major tonic pedal in the bass of the orchestra.

At the time he composed the Requiem, Brahms’ only large-scale orchestral work was the D minor Piano Concerto, whose scoring had given him great trouble. The orchestration of A German Requiem lacks the subtlety of Brahms’ later symphonic works, and a very few pages even show signs of misjudgment. In particular the double fugue just mentioned can give trouble: an insensitive timpanist in the first Vienna performance played his part in the tonic pedal so loudly that he swamped everything else.

The overall effect of the orchestration is to paint the sombre tones of Brahms’ conception. Like Cherubini before him and Fauré after, he responds to the service for the dead by using violas and lower strings in many places to the exclusion of the violins, and in the first movement he also banishes the bright tones of clarinets and trumpets. Piccolo and harp are used to lighten and vary the texture in a medium-sized Romantic symphony orchestra. The relation of the vocal soloists to the choir is that of a single voice leading the people, a personal voice to which the choir responds by repeating and underlining its utterances.

Brahms was never more personal, nor more true to his nature than in this ambitiously scaled work. For that reason, perhaps, it has remained the litmus test of attitudes to Brahms’ art. The pro-Wagner faction – of which George Bernard Shaw made himself the spokesman in England – could never accept its creative musical conservatism, or, one suspects, the firmly contained emotion with its basis in a longing for religious certainty. For others, and especially those who share some of the troubles of Brahms’ soul, the effect of this masterful meditation on death, dissolved into music by an ultimately lonely man, can be overwhelmingly moving.

David Garrett © 1989

First Performance:

Good Friday 1868, Bremen Cathedral.

Most recent WASO performance:

3-4 August 2012. Simone Young, conductor.

Instrumentation:

piccolo, two each of flutes, oboes, clarinets,

bassoons and contrabassoon; four horns, two

trumpets, three trombones and tuba;

timpani, harp, organ and strings.

Glossary

Oratorio – a substantial work for singers and orchestra based on a religious text.

Cantata – a work for voices and orchestra consisting of arias, recitatives and choruses.

Contrapuntal – Of, relating to, or incorporating counterpoint (two or more lines of music or melodies that are played at the same time).

Fugal – in the style of a fugue, characterised by imitation between different parts or instruments, which enter one after the other. The Latin word fuga is related to the idea of both ‘fleeing’ and ‘chasing’.

Brahms – A German Requiem

Text & Translation

Translate to English

1. Chorus

Selig sind, die da Leid tragen,

denn sie sollen getröstet werden.

Die mit Tränen säen,

werden mit Freuden ernten.

Sie gehen hin und weinen

und tragen edlen Samen,

und kommen mit Freuden

und bringen ihre Garben.

2. Chorus

Denn alles Fleisch, es ist wie Gras,

und alle Herrlichkeit des Menschen

wie des Grases Blumen.

Das Gras ist verdorret

und die Blume abgefallen.

So seid nun geduldig, lieben Brüder,

bis auf die Zukunft des Herrn.

Siehe, ein Ackermann wartet

auf die köstliche Frucht der Erde

und ist geduldig darüber, bis er empfahe

den Morgenregen und Abendregen.

So seid geduldig.

Aber des Herrn Wort

bleibet in Ewigkeit.

Die Erlöseten des Herrn

werden wiederkommen

und gen Zion kommen mit Jauchzen;

Freude, ewige Freude

wird über ihrem Haupte sein;

Freude und Wonne werden sie ergreifen,

und Schmerz und Seufzen

3. Solo (Baritone) with Chorus

Herr, lehre doch mich,

dass ein Ende mit mir haben muss

und mein Leben ein Ziel hat

und ich davon muss.

Siehe, meine Tage

sind einer Hand breit vor dir,

und mein Leben ist wie nichts vor dir.

Ach, wie gar nichts sind alle Menschen,

die doch so sicher leben.

Sie gehen daher wie ein Schemen

und machen ihnen

viel vergebliche Unruhe;

sie sammeln und wissen nicht,

wer es kriegen wird.

Nun, Herr,

wes soll ich mich trösten?

Ich hoffe auf dich.

Der Gerechten Seelen

sind in Gottes Hand,

und keine Qual rühret sie an.

4. Chorus

Wie lieblich sind deine Wohnungen,

Herr Zebaoth!

Meine Seele verlanget und sehnet sich

nach den Vorhöfen des Herrn;

mein Leib und Seele freuen sich

in dem lebendigen Gott.

Wohl denen,

die in deinem Hause wohnen,

die loben dich immerdar!

5. Solo (Soprano) with Chorus

Ihr habt nun Traurigkeit;

aber ich will euch wiedersehen,

und euer Herz soll sich freuen,

und eure Freude soll niemand

von euch nehmen.

Ich will euch trösten,

wie einen seine Mutter tröstet.

Sehet mich an:

ich habe eine kleine Zeit

Mühe und Arbeit gehabt

und habe grossen Trost funden.

6. Solo (Baritone) with Chorus

Denn wir haben hier keine

bleibende Statt,

sondern die zukünftige suchen wir.

Siehe, ich sage euch ein Geheimnis:

Wir werden nicht alle entschlafen,

wir werden aber alle verwandelt,

und dasselbige plötzlich,

in einem Augenblick,

zu der Zeit der letzten Posaune.

Denn es wird die Posaune schallen,

und die Toten werden

auferstehen unverweslich,

und wir werden verwandelt werden.

Dann wird erfüllet werden

das Wort, das geschrieben steht:

Der Tod ist verschlungen in den Sieg.

Tod, wo ist dein Stachel!

Hölle, wo ist dein Sieg!

Herr, du bist würdig, zu nehmen

Preis und Ehre und Kraft,

denn du hast alle Dinge erschaffen,

und durch deinen Willen

haben sie das Wesen

und sind geschaffen.

7. Chorus

Selig sind die Toten,

die in dem Herren sterben

von nun an.

Ja, der Geist spricht,

dass sie ruhen von ihrer Arbeit,

denn ihre Werke folgen ihnen nach.