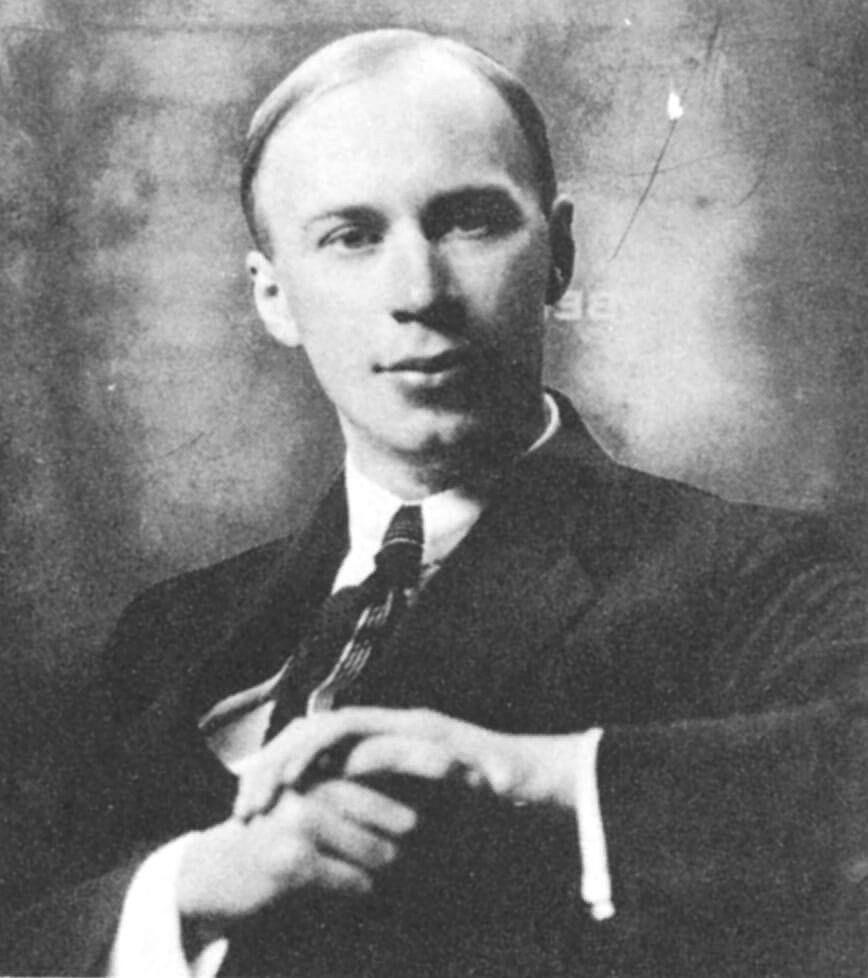

Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953)

Classical Symphony

(Symphony No.1 in D), Op.25

Allegro

Larghetto

Gavotte (Non troppo allegro)

Finale (Molto vivace)

A 20th-century composer writes in a style much simpler, and less obviously modern, than his other music, and calls his piece Classical Symphony, harking back to the music of Mozart and Haydn. What is going on? After Prokofiev wrote this symphony in 1917, audiences everywhere thought they knew. This time, at least, he had written music which was easy to understand and enjoy. It quickly became one of Prokofiev’s best-loved works, second in popularity only to Peter and the Wolf. But the composer was really up to some harmless mischief when he gave this piece its title. He admitted later he wanted to ‘tease the geese’, and he laughed at the critics’ complicated discussions about his ‘Neo-classical’ style, of which the Classical Symphony was supposed to be so striking an example.

Prokofiev chose the style of the Classical composers, but not as a tribute to their music. He later told his friends he had set himself an exercise, in the summer of 1917, between the February and October Revolutions. He had gone to stay in a country house where there wasn’t a piano. Having noticed that ‘thematic material composed without the piano was often better’, he wanted to see whether he could compose a whole work in his head, without using the piano as he usually did. He thought this ‘difficult journey’ would be easier if he deliberately adopted a simpler style and form.

Prokofiev loved playing musical games (he was also a champion chess player), and the Classical is a cheerful, humorous symphony.

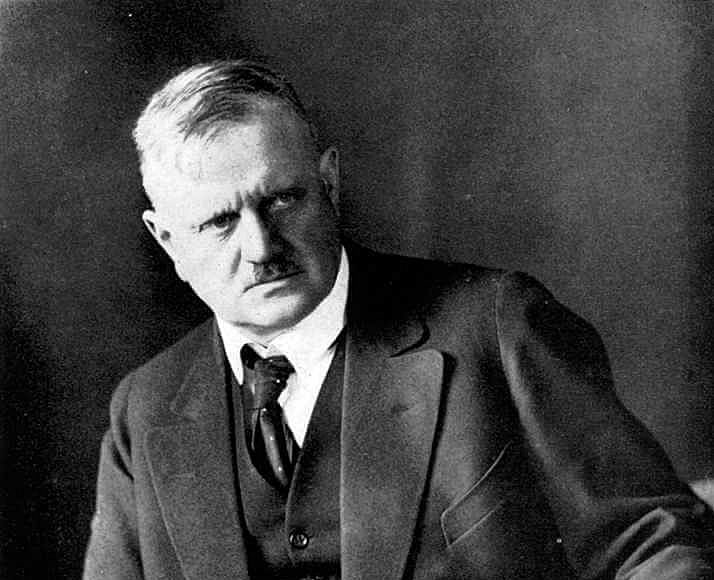

Haydn’s music is often like this too, and Prokofiev mentioned that 18th-century symphonist as his model. He had heard and studied Haydn’s symphonies in Tcherepnin’s conducting classes, and it was for a ‘Haydn’ or Classical orchestra that he wrote – pairs of wind instruments, horns, trumpets, timpani and strings. Prokofiev knew the ‘rules’ of musical language which had been codified from the procedures of ‘Classical’ symphonists such as Haydn. But he didn’t imitate Haydn slavishly: ‘It seemed to me,’ he wrote, ‘that if Haydn had lived to our day he would have retained his own style while at the same time absorbing something of the new. This was the kind of symphony I wanted to write.’

With hindsight we can see that the Classical Symphony has much the same characteristics as all Prokofiev’s best music. He plays similar games, such as taking a conventional melody and shifting it into a harmonic frame which seems disconnected. This produces the feeling, as Prokofiev’s friend Nicholas Nabokov said, that the melody has been refreshed by being harmonically mishandled.

Prokofiev did not feel bound by 18th century harmonic conventions: for instance, at the very beginning he states his subject in the key of D, then without any pretence at modulation, in C. The writing for the strings tends to be high up in the compass of the instruments, which gives the Classical Symphony its elegant, witty sounding texture: as though themes by Haydn were being played an octave higher than he would have written them.

This cheerful style was one way Prokofiev rebelled against the late-Romantic atmosphere, steamy with philosophy, literature and mysticism. This symphony composed in 1917 was part of a musical revolution. But it was also very Russian and traditional, in its somewhat mechanical concept of form as an external structure, since Russian 19th-century composers had tended to pour their music into existing formal moulds. The Gavotte, composed in 1916, before the rest of the music, is an old French dance form. Its inclusion in the symphony, in the place of the Classical minuet, shows that Prokofiev was drawn, whether consciously or not, to an older, even more formal style than is found in the symphonies of Mozart and Haydn. His departure from their formal example comes, significantly, in music based on the dance; which, as Prokofiev’s own ballets show, suited his gifts so well.

© David Garrett

First performance:

21 April 1918, Petrograd. Composer conducting.

Most recent WASO performance:

16-17 March 2012. Nicholas Carter, conductor.

Instrumentation:

two each of flutes, oboes, clarinets and bassoons; two horns, two trumpets; timpani and strings.