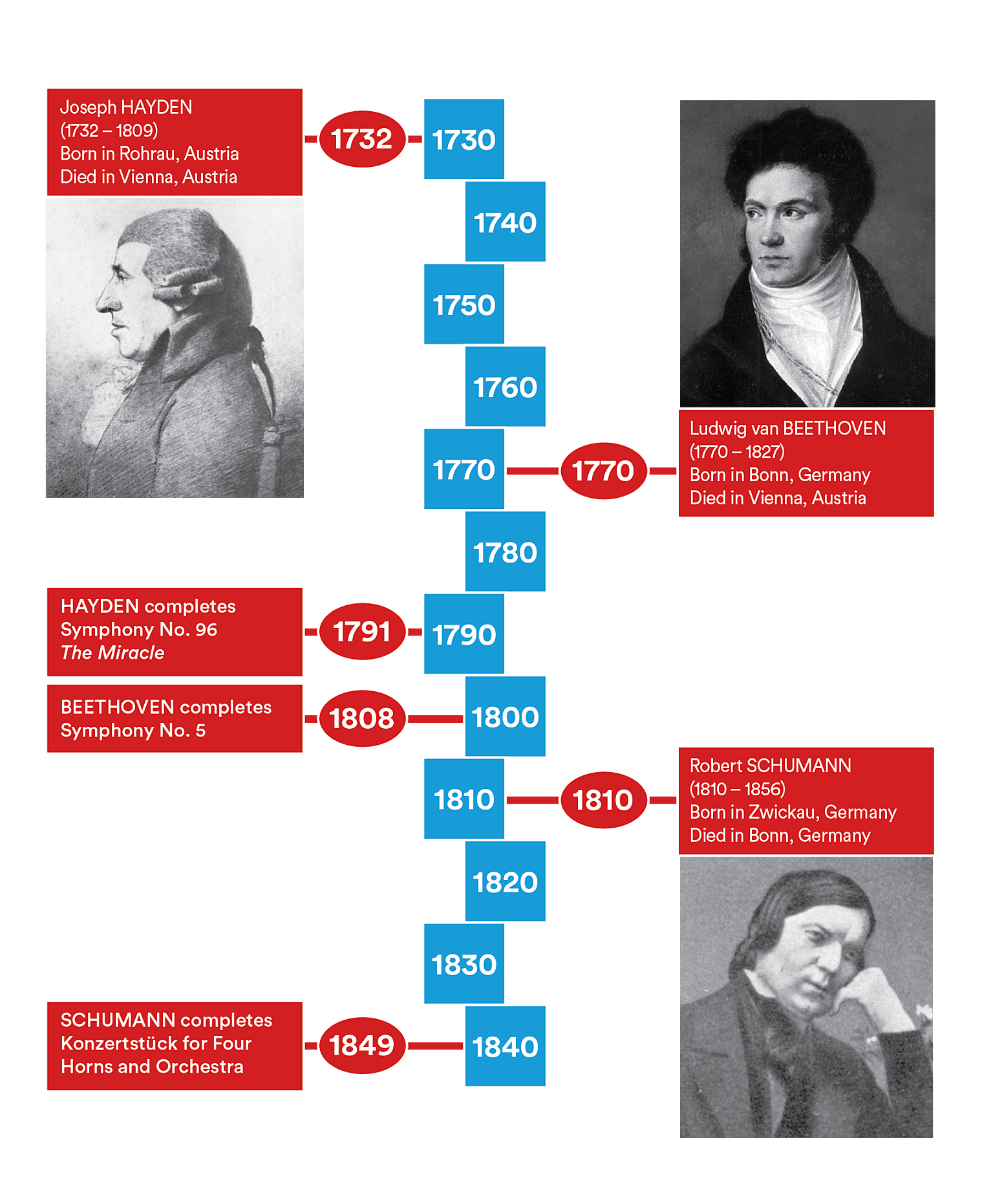

Robert Schumann (1810-1856)

Konzertstück (Concert Piece) in F for four horns and orchestra, Op.86

Lebhaft

Romanze (ziemlich langsam,

doch nicht schleppend) –

Sehr lebhaft

Orchestral horn players form a guild united by the tightrope-walking perils associated with their craft. Reputed the trickiest instrument to play, the French horn can also be one of the most exciting and evocative. These qualities come multiplied by four in a work exposing the four players of a standard section as soloists. Until recently, Schumann’s Konzertstück was known more by reputation and from recordings than in concert; nowadays, horn sections over the world are queuing up begging their orchestra’s program planners to let them have a go. This is a sign of the general rise of skill and confidence in the guild, but it is also part of a revaluation of Schumann’s orchestral music. He himself, revealing that he had ‘written the piece with great passion’, thought it ‘one of my best things’. The passion must have come from knowing that it could be performed – it was – but after that first performance at the Leipzig Gewandhaus in February 1850 the piece languished, deemed unperformable for its sheer difficulties, and remained for long, rather than a repertoire piece, a historical landmark: the first important concerto-like work intended, from the first, for valved horn.

That Schumann emerges as a pioneer of the use of the valved horn, in his symphonies, and especially his solo pieces for the instrument, has to do with his exposure to skilled players. One in particular, Joseph Rudolf Levy (or Lewy), was the leader of the horns in the Dresden Court Orchestra, and it was in Dresden, in 1849, that Schumann composed his Adagio and Allegro Op.70, for horn and piano. He was so excited by it that the very next day he began composing a ‘four horn work’, as he called it. Two days later he finished the sketch; a few weeks more and the orchestration was complete. On 15 October 1849 Schumann attended a rehearsal of his new work at Levy’s home. It was not Levy and his colleagues, however, who gave the first performance on 25 February 1850, but their counterparts in the Leipzig Gewandhaus orchestra (Pohle, Jehnichen, Leichsenring and Wilke) with Julius Rietz conducting. Levy’s virtuosity (and perhaps Schumann’s sense that it might not be wise to spread the difficulties too much) may be attested by the Horn 1 part, which is extremely high and has long passages with no rest (arrangements have been published which redistribute the material somewhat among the players). Perhaps sensing that the piece was unlikely to find many performers, the publishers brought out a version for piano and orchestra. This arrangement published after Schumann’s death is not by him, but possibly by Joachim Raff.

Listening Guide

The title is revealing, and not a misnomer for a concerto in disguise. With a tradition going back at least to Weber’s very influential Konzertstück of c.1821, for piano and orchestra, it describes a form favoured by many Romantic composers, in which the movements of a concert piece with soloist(s) are unified by continuity and by thematic interrelations. The solos can be as brilliant as you like, and are not restricted as to where they can intervene. In Schumann’s Konzertstück they announce themselves after a pair of prefatory chords with a sonorous fanfare. The writing for the quartet of horns is notable throughout the work for giving all four a lot to do most of the time. But the texture is inventive and never thick, despite Schumann’s characteristic doublings in the orchestral parts, where he matches the soloists with two (hand) horns and three trombones, as well as trumpets and a piccolo for added éclat. Some of the solo horn writing has been called ‘recklessly brilliant’: the first horn part frequently rises to a top (concert) F, only to be topped by truly vertiginous As (some of these were removed before the first edition was published in 1851). Nor are the horns’ lyrical possibilities neglected in the contrasting passages. The second movement, Romanze, anticipates the atmosphere and the brassy sounds of the ‘cathedral’ movement of Schumann’s Rhenish Symphony of 1850, in the broad melody of its middle section, which recurs in thematic transformation in the finale. This follows directly, linked by a trumpet call. It is a playful movement, one of whose episodes salutes, as so often in Schumann, Felix Mendelssohn – in this case his Midsummer Night’s Dream music. The final cadential flourish is marked by Schumann ‘with bravura’. Not only the guild will applaud this balancing act! Unplayable? Not any more…

David Garrett © 2006

First performance:

25 February 1850, Leipzig. Conducted by Julius Rietz.

Most recent WASO performance:

5 March 2005. Matthias Bamert, conductor.

Instrumentation:

two flutes and piccolo, two oboes, two clarinets and two bassoons; two horns, two trumpets and three trombones; timpani and strings. timpani and strings.