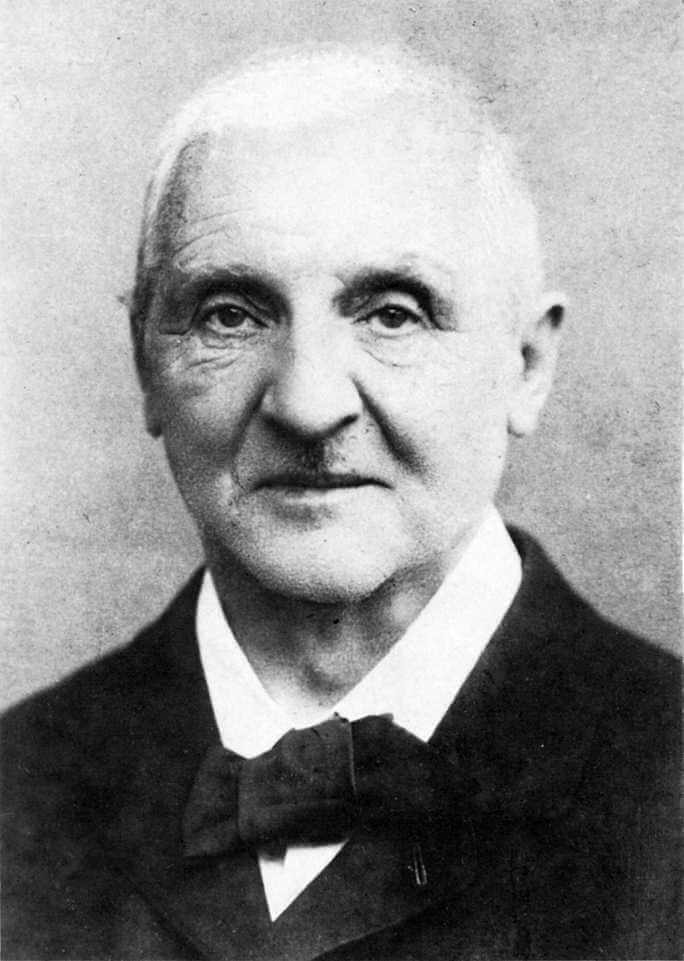

Anton Bruckner (1824-1896)

Symphony No.7 in E

Allegro moderato

Adagio. Sehr feierlich und sehr langsam

Scherzo. Sehr schnell

Finale. Bewegt, doch nicht schnell

At the age of 60, the diffident, pious Anton Bruckner suddenly achieved international fame as a composer with the Seventh Symphony. Bruckner had moved to the imperial capital in 1868 to take up a position at the Vienna Conservatory, and travelled as far afield as Paris and London as one of the greatest organists of the age. But until the mid-1880s, his own music had failed to find a foothold in Vienna’s musical life – partly the result of Bruckner’s idolisation of Wagner, which was anathema in a city where Brahms presided as the resident Great Composer, aided by powerful critics like Eduard Hanslick.

Back in 1873 Bruckner had approached Wagner for permission to dedicate his Third Symphony to the ‘Master of all masters’. While working on the Seventh Symphony, Bruckner later remarked, ‘One day I came home and felt very sad. It occurred to me that the Master would soon die, and at that moment the C sharp minor theme of the Adagio came to me.’ And, indeed, during the composition of the slow movement, Bruckner heard the news of Wagner’s death, incorporating his grief into the final pages of the movement. But the piece as a whole was conceived before Bruckner’s premonition.

The melody with which the first movement begins is a long and very beautiful tune that outlines the key of E major over two octaves, before moving through seemingly distant keys; a ‘false’ close gives way to yet more varied phrases and hints of further tonal exploration before returning to E major for a fuller restatement of the melody itself. The movement displays Bruckner’s habitual use of three contrasting groups of themes, the second of which is what he liked to call a ‘song-period’, and out of these he spins a lengthy series of contrasting musical worlds, using key-relationships for maximum dramatic effect.

The key of C sharp minor, closely related to the work’s ‘home key’ of E major, is avoided throughout the first movement so that its appearance in the second is more emphatic. In this, the premonitory elegy for Wagner, Bruckner introduces four Wagner tubas. As in the slow movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, ‘very slow and very solemn’ material is contrasted with a theme in a different mood, speed and key. Bruckner was working on the climax of the movement – a majestic passage in C major – when he heard of Wagner’s death. He quotes a motive from his Te Deum (associated with the words ‘Non confundar in aeternum’ – let me never be put to shame) but it is in the coda which follows with its almost Wagnerian horn calls that Bruckner farewells the Master.

After the catharsis of the Adagio, Bruckner produces one of his most delightfully energetic scherzos. Again, the movement’s key – A minor – has been avoided so far. The octave and perfect fifth which constitute the theme of this section are the most stable intervals in tonal music, but Bruckner effortlessly plays this stability off against a series of unexpected excursions into different keys, and it proves an amusing contrast to the central Trio section.

The Finale is constructed out of four sections: the first is in E major, and deliberately recalls the first movement in its use of the stable intervals of the common chord; the second and third sections are, respectively, in keys a third above and below E; finally the fourth section, using material based on the first, charts the journey from the key of A back to the home key.

The Seventh’s premiere was in the Leipzig Gewandhaus under Arthur Nikisch in 1884 and the applause lasted for 15 minutes. Wagner conductor Hermann Levi declared it ‘the most significant symphonic work since 1827’. Soon it had been heard throughout Germany as well as in New York, Chicago, Amsterdam, Budapest and London. When it finally was played in Vienna in 1886, Hanslick, predictably, wrote it off as ‘unnatural, blown up, unwholesome, and ruinous’ and his colleague Kalbeck memorably wrote, ‘It comes from the Nibelungen and goes to the devil!’ Actually, it is music about going to heaven, or, as British composer Robert Simpson puts it, ‘a patient search for pacification’.

Adapted from a note by Gordon Kerry © 2002

First performance:

30 December 1884, Leipzog. Arthur Nikisch conducting.

First WASO performance:

20-21 October 1972. Tibor Paul, conductor.

Most recent WASO performance:

26-27 August 2011, Paul Daniel conductor.

Instrumentation:

two each of flutes, oboes, clarinets and bassoons; four horns, four Wagner tubas, three trumpets, three trombones and tuba; timpani, two percussion and strings.