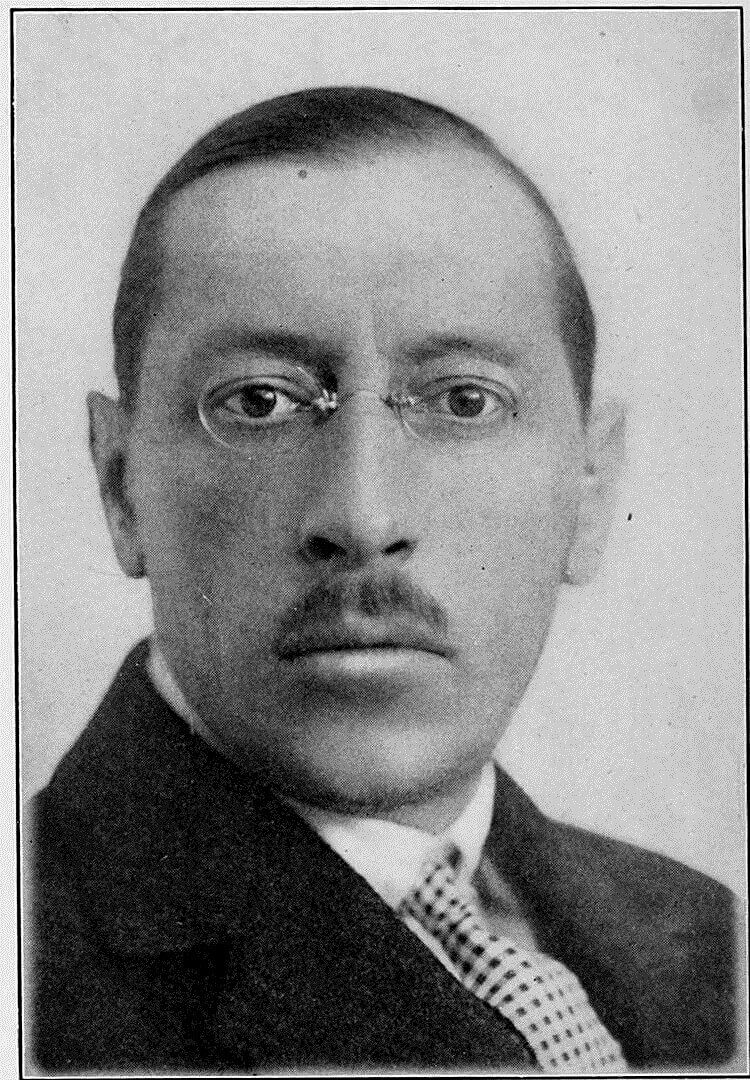

Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971)

Le Sacre du printemps (The Rite of Spring)

Part 1 L’Adoration de la terre (Adoration of the Earth)

Introduction

Danse des adolescentes (Dance of the Young Girls)

Jeu du rapt (Ritual of Abduction)

Rondes printanières (Spring Rounds)

Jeux des cités rivales (Games of the Rival Tribes)

Cortège du sage (Procession of the Sage)

L’Adoration de la terre (Adoration of the Earth)

Danse de la terre (Dance of the Earth)

Part 2 Le Sacrifice

Introduction

Cercles mystérieux des adolescentes (Mystic Circles of Young Girls)

Glorification de l’élue (Glorification of the Chosen Virgin)

Evocation des ancêtres (Evocation of the Ancestors)

Action rituelle des ancêtres (Ritual of the Ancestors)

Danse sacrale – L’élue (Sacrificial dance – The Chosen Virgin)

The trouble started as soon as the solo bassoon began its plaintive version of a Lithuanian folksong. Heckling, spreading from the gallery of the new Théâtre des Champs-Élysées into the stalls, became so loud that the choreographer Nijinsky stood on a chair in the wings shouting directions at the dancers who could no longer hear the orchestra. The theatre’s electrician frantically flicked the house lights on and off to try and settle the audience; there was a brawl and the police had to be called. The orchestra soldiered on and gave what those who could hear it describe as a fine performance.

The riot at The Rite of Spring’s premiere is legendary – scholar Richard Taruskin says that Stravinsky ‘spent the rest of his long life telling lies about it’! But it was not the score that caused a fracas among the Philistines. (Debussy’s Jeux – also premiered by Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes – had been booed a fortnight before.) Nijinsky’s choreography (described by Jean Cocteau as ‘automatonlike monotony’) caused the most offence. A year later Pierre Monteux conducted a concert performance in Paris, and Stravinsky experienced the success ‘such as composers rarely enjoy’ as he was carried through the streets like a sporting hero on the shoulders of his audience.

There had, though, never been anything like it. In his two previous ballets for Diaghilev’s company Stravinsky had mined Russian folklore and fairytale: The Firebird was a story of enchanted princesses, ogres and a magic phoenix; Petrushka’s protagonists are fairground puppets. Certainly since the political upheavals of 1905, and arguably well before, folklore had been a powerful force in Russian art. But in 1910, Stravinsky had a vision of ‘wise elders, seated in a circle, watching a young girl dancing herself to death…to propitiate the god of spring’ and drafted a scenario with the designer Nicholas Roerich. (They later fought over whose idea it was.) The work is, as scholar Stephen Walsh puts it, ‘hardly a “story” ballet with characters [but] a strict “liturgical” sequence, a sequence which, we understand, will always happen this way, with different participants but the same meaning’. Stravinsky’s Russian title for the work is better translated as Holy Spring, and its subtitle is ‘Scenes from Pagan Russia’.

Musicologist Paul Griffiths quotes Stravinsky’s long-time assistant Robert Craft’s assertion that the composer ‘repeatedly said that he wrote The Rite of Spring in order “to send everyone” in his Russian past, Tsar, family, instructors, “to hell”’.

This suggests that The Rite attempts to be a ‘clean slate’ untouched by the corruptions of musical ‘civilisation’. The composer later said that he was ‘the vessel through which The Rite passed’, and the sketches suggest that many of his ideas sprang, fully formed, onto the page. At the same time, Stravinsky’s sumptuous orchestration and harmony could not have existed without the music of Glinka and Rimsky-Korsakov; Debussy rightly called the score ‘primitive music with all modern conveniences’. Moreover, Stravinsky long maintained that the opening bassoon melody, whose timbre suggests traditional dudki or reed

pipes, was the only folk tune in the score, but the publication of his sketchbooks in 1969 showed that he had copied out several tunes that found their way into the work.

These tunes are usually relevant in subject matter to the events of the ballet, but as Stephen Walsh puts it, Stravinsky reduces them ‘to simple essences which could then be used as motives of rhythmic and ostinato treatment’.

Walsh goes on to say, ‘What nobody seems to have done before The Rite of Spring was to take dissonant, irregularly formed musical “objects” of very brief extent and release their latent energy by firing them off at one another like so many particles in an atomic accelerator.’ The ‘cells’ that Stravinsky creates out of the simple rhythmic essences of folk tunes are repeated, distorted by the addition of extra beats, interrupted by contrasting cells. The Rite, then, is the ultimate abstraction of Stravinsky’s early ‘Russian’ style, and the foundation for much of his subsequent music.

Gordon Kerry © 2005/13

First performance:

The Ballets Russes gave the first performance of The Rite of Spring on 29 May 1913 at the Théâtre des ChampsÉlysées in Paris. The conductor was Pierre Monteux and the choreographer, Vaslav Nijinsky. The principal dancers were Maria Plitz (Chosen Virgin), Ludmila Guliuk (Old Woman) and Alexander Vorontzov (Sage).

First WASO performance of complete work:

7-8 August 1992. Jorge Mester, conductor.

Most recent WASO performance:

5-6 August 2016. Simone Young, conductor.

Instrumentation:

two piccolos, three flutes, alto flute, four oboes, two cors anglais, three clarinets, two bass clarinets, E flat clarinet, four bassoons, two contrabassoons, eight horns, two Wagner tubas, four trumpets, bass trumpet, piccolo trumpet, three trombones, two tubas, timpani, percussion and strings.