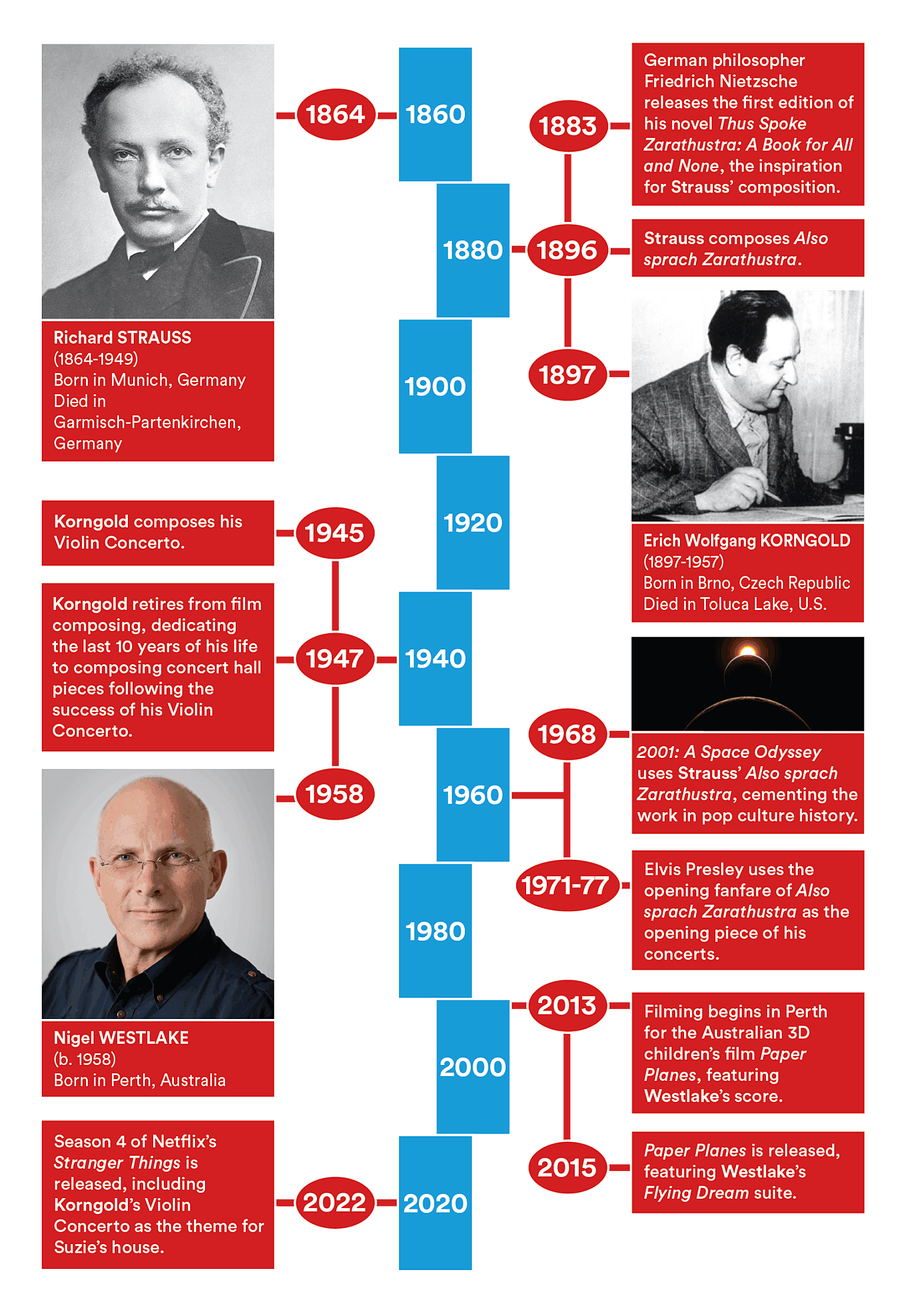

Erich Wolfgang Korngold

(1897-1957)

Violin Concerto in D, Op.35

Allegro nobile

Romance: Andante

Finale: Allegro assai vivace

Leaving most of his family behind, Korngold left Vienna for Hollywood in January 1938 to compose music for The Adventures of Robin Hood, expecting to return in a few months for the premiere of his opera, Die Kathrin. But Germany’s annexation of Austria in March made a return home impossible, and his family escaped Austria on the last unrestricted train.

Films were now Korngold’s only source of income. When his father berated him for not writing absolute music, Korngold replied that if anyone in America wanted to perform his music they knew where to find him. His wife said later: ‘It was almost as if he had made a vow not to write any more until Hitler was defeated.’

The Violin Concerto was to be Korngold’s return to the concert hall. Ideas for this work seem first to have surfaced in 1937. A theme from the film Another Dawn, scored that year, is the principal melody of the concerto’s first movement; and a transformation of the opening title theme for that year’s The Prince and the Pauper forms the basis for the concerto’s finale.

But Korngold did no serious work on the piece until the war in Europe was over. The violinist Bronislaw Huberman revived a joke that dated back to Korngold’s teenage years: ‘Erich, where’s my violin concerto?’ At dinner one night in 1945, Huberman asked the usual question, whereupon Korngold went to the piano and played the opening theme. Huberman cried: ‘That’s it! That will be my concerto…’

When the concerto was ready for performance, Huberman was somewhat vague about when he might get around to performing it, yet was equally anxious that no-one else would play it before him. When Jascha Heifetz expressed interest in it, Korngold did not hesitate. ‘Huberman,’ he told his friend, ‘I haven’t been unfaithful yet, I’m not engaged…but I have flirted.’ Huberman’s death a short time later brought this chapter in the concerto’s life to an end.

For Korngold, the concerto symbolised his re-emergence into a musical mainstream in which he no longer felt completely secure. He remains true to his instincts in the work, and was particularly nervous about the critics’ response to his frankly emotional musical language. In the weeks before the premiere, he wrote of the work: ‘I want a confirmation, an answer to a question of decisive importance for me: is there still a place and a chance for music with expression and feeling, with long melodic themes, formed and developed on the principles of the classic masters – music conceived in the heart and not constructed on paper?’

The premiere, in St Louis with Heifetz, was a triumphant success with critics and public alike. But Korngold was rightly concerned at how it would be received when Heifetz took it to New York a few weeks later. Irving Kolodin’s famous jibe in the New York Sun, ‘More corn than gold,’ hurt the composer deeply. Posterity’s answer to Korngold’s question has been mixed: the work languished on the fringes of the repertoire until the 1980s, by which time the influence of contemporary music’s style police had begun to wane. The concerto is now the most performed of all Korngold’s concert works.

By 1945, Korngold’s enjoyment of the film-scoring process had abated, and he was concerned that some of his best musical ideas were disappearing as each film was taken out of circulation. He had no hesitation in re-casting themes from his films in his concert music.

The first movement is primarily lyrical, and casts the soloist as a storyteller. The violin joins the orchestra from the opening bars, with the theme adapted from the one Korngold first wrote for Another Dawn. The gentle, romantic second subject was first used in the 1938 film Juarez.

The Romance is almost a love scene played between the soloist and the orchestra. The solo violin plays almost continuously, for the most part spinning high, songful phrases over a carpet of gentle string accompaniment. Korngold’s fondness for orchestral keyboards is particularly evident in this movement: the orchestral forces include vibraphone and celeste. For the Romance’s lavish outpouring of melodic ideas, Korngold drew on his Anthony Adverse score, but created anew the brief, haunting misterioso episode at the movement’s core. This highly chromatic idea returns to conclude the movement.

In a similar manner to the last movement of Samuel Barber’s Violin Concerto, Korngold establishes a decisive change of mood in the finale. In effect it is a set of variations on a theme he first created for The Prince and the Pauper.

Phillip Sametz © 2000

First performance:

15 February 1947, St Louis. Vladimir Golschmann conducting. Jascha Heifetz soloist.

Most recent WASO performance:

8-9 October 2010. Renaud Capuçon (violin). Otto Tausk (conductor).

Instrumentation:

two flutes (2nd also piccolo), two oboes (2nd also English horn), two clarinets, bass clarinet, two bassoons (2nd also contrabassoon); four horns, two trumpets, trombone; timpani, bass drum, cymbals, tubular bells, gong, vibraphone, xylophone, glockenspiel, celesta, harp and strings.