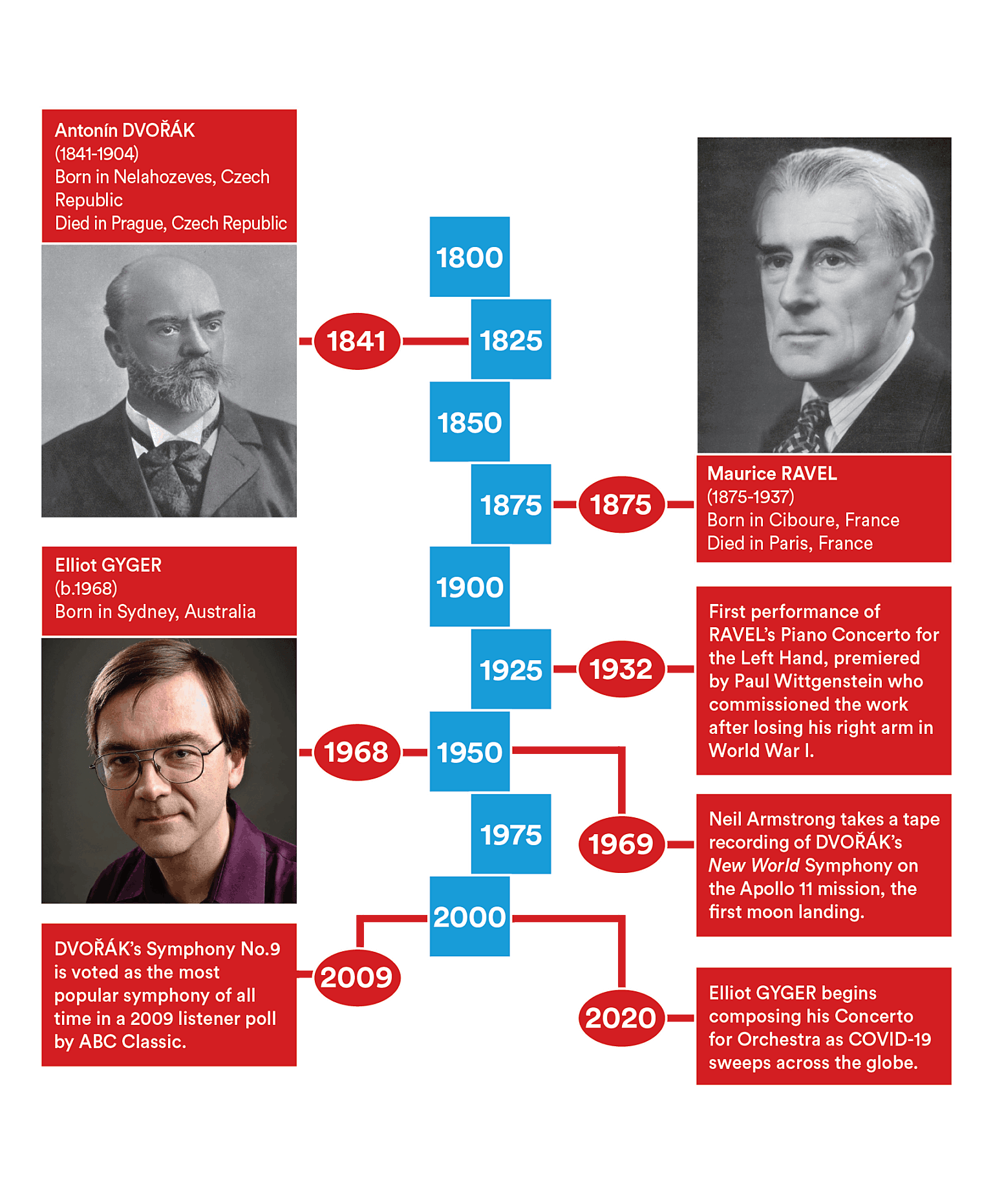

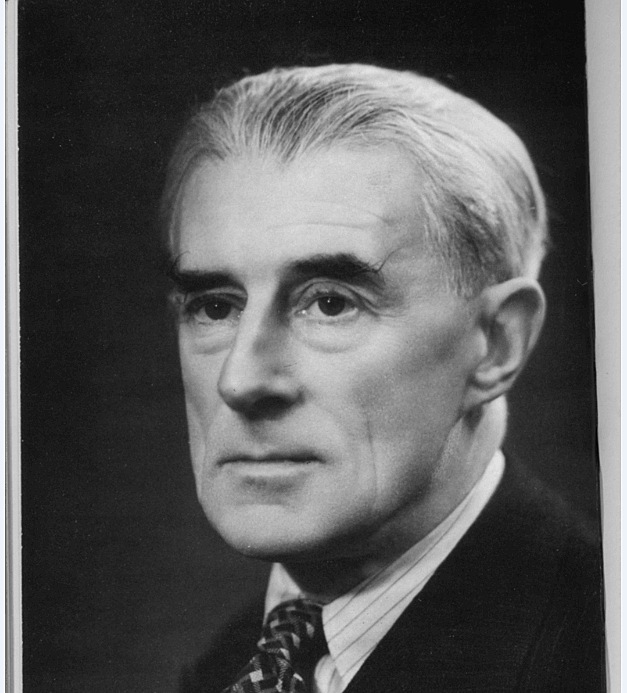

Maurice Ravel (1875-1937)

Concerto in D for the Left Hand

Lento –

Andante –

Allegro –

Tempo primo

Ravel’s Concerto for the Left Hand is of such ferocious technical difficulty that its dedicatee and first performer, Paul Wittgenstein, begged the composer for some simplification. Ravel, however, was a little too fond of his ‘neat and nice labours’, according to the London Musical Times, and refused outright.

The first performance occurred not with the composer at the helm, but with Robert Heger conducting, in Vienna, prompting much speculation about ‘artistic personalities’. It was not until 1933 that the concerto was heard in Paris. All differences apparently resolved, Ravel conducted the Orchestre Symphonique de Paris, while Wittgenstein performed.

We can be glad today of Ravel’s pride in his ‘neat and nice labours’, as the Concerto for the Left Hand occupies a unique place in the repertoire. But Wittgenstein can

hardly be accused of faint-heartedness. Brother of the philosopher Ludwig, he lost his right arm at the Russian front in 1914, but resolved to continue his career as concert pianist. He commissioned works for left hand alone from Prokofiev, Hindemith and Britten. Ravel’s Left Hand Concerto was published in 1931, as Wittgenstein’s ‘exclusive property’.

Compositions for the left hand were not without precedent – pianists, it seems, had been losing their arms or hands or disabling themselves since time immemorial. And for some reason the right hand was always the first to go. Schumann famously ruined his right hand through ‘overdone technical studies’, perhaps involving the use of a mechnical device; in the 19th century a Count Geza Zichy contributed a concerto for left hand after losing his right arm hunting. Leopold Godowsky, who lost the use of his right hand in a stroke, had by good fortune previously composed 22 studies on Chopin etudes for left hand alone. Ravel studied Saint-Saëns’ Six Studies for the Left Hand in his preparation for this concerto, and may have been exposed to Scriabin’s Prelude and Nocturne for Left Hand Alone. Ravel’s solutions to the problem of ‘half a pianist’, however, are entirely his own. The difficulty, he claimed, was ‘to avoid the impressions of insufficient weight in the sound-texture,’ something he addressed by reverting to the ‘imposing style of the traditional concerto.’

The Left Hand concerto and the G major concerto for both hands were composed simultaneously, in the years 1929 to 1931, but the two works could scarcely be more different. The Concerto in G is a popular and enduring work, but essentially a divertissement – a good-hearted rollick. Perversely, the composer saves his deepest statements, and his greatest virtuosity, for his ‘lame’ work. It unfolds almost as a

Concerto Grosso, with the pianist responding to the orchestra in dazzling

cadenzas. Here the soloist really is tragic hero, triumphing against orchestra and handicap.

The concerto begins with cellos and double bass in their lowest register, creating less a sound than mere a feeling of darkness. A contrabassoon in its lowest range introduces fragments of the theme. (This passage, incidentally, was originally scored for the historical curiosity of the Sarrusophone – a bizarre hybrid of saxophone and bassoon, designed for use in military bands.) Other instruments gradually enter the fray until the texture builds to an enormous climax, and the piano enters, in a cadenza of extraordinary virtuosity. The orchestra responds and builds to an even greater plane, before the piano returns, and surprises us with transparent lyricism. This introduces the central section, of distinct jazz influence. Parallel

triads skid downwards through the piano; a

tarantella recalls the opening melody. Finally, Ravel returns to his opening material, and a yet more dazzling piano cadenza. The piece ends almost too abruptly, with what the composer described as a ‘brutal peroration’.

Musically probably the supreme work for left hand alone, the concerto is also one of the most difficult. Ravel makes few concessions to single-handedness, and the piano part is expressed in virtuosic, stereo sound. The pianist Alfred Cortot suggested that a two-handed arrangement would do nothing to diminish the music, but would rather allow it a more permanent place in the repertory. The Ravel family refused. The concerto exists as unique piece of musical illusion, and perhaps they wished to preserve this. The first performances received an excited audience and critical response, not least because of the work’s outpouring of sentiment. The concerto’s overt emotionalism refutes Stravinsky’s dismissal of the composer as ‘the Swiss watch-maker’. Prunières noted wistfully that he should have liked Ravel to have ‘been able to let us observe more frequently what he was guarding in his heart, instead of accrediting the legend that his brain alone invented these admirable sonorous fantasmagorias. From the opening measures [of the concerto], we are plunged into a world to which Ravel has but rarely introduced us.’

It was to be short-lived introduction. Ravel soon exhibited symptoms of the debilitating brain disease that was to end his life. He composed three songs for a projected film about Don Quixote which, along with the two piano concerti, became his unexpected swansong.

Anna Goldsworthy © 1999

First performance:

1 May 1932, Vienna. Paul Wittgenstein, piano. Robert Heger conducting.

Most recent WASO performance:

11-12 November 1994. Gary Graffman, piano. Marcello Viotti, conductor.

Instrumentation:

three each of flutes (3rd = piccolo), oboes (3rd = cor anglais), four clarinets (two doubling piccolo and bass clarinet) and three bassoons (3rd – contrabassoon); four horns, three trumpets, three trombones and tuba; timpani, four percussionists, harp and strings.