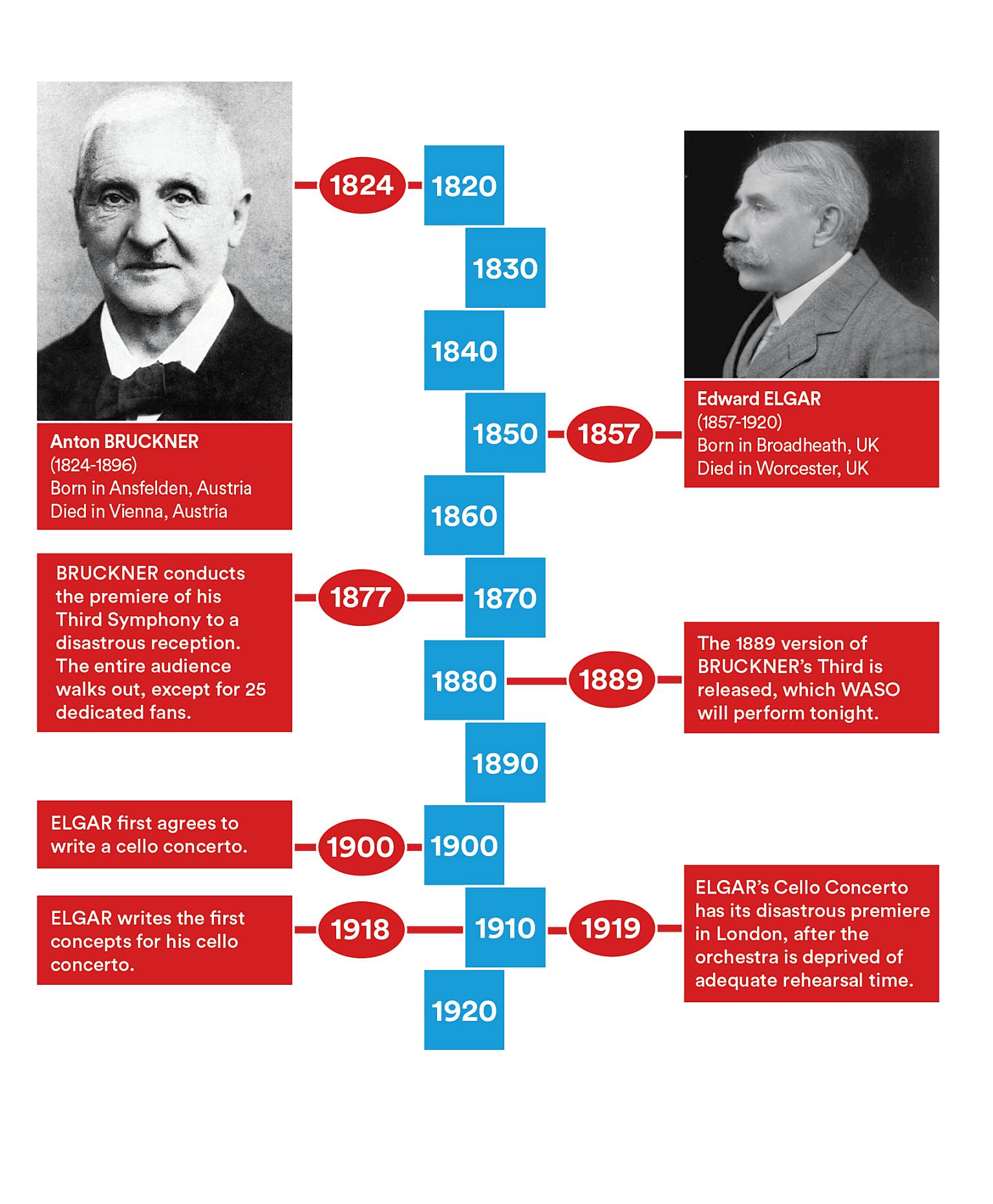

Anton Bruckner (1824-1896)

Symphony No.3 in D minor (1889 version)

Mehr bewegt, misterioso

Adagio, bewegt, quasi Andante

Ziemlich schnell

Allegro

‘…I am still too deeply moved by its reception by the Philharmonic audience, who must have recalled me at least twelve times, over and over again…’ [Bruckner to Göllerich - December 1890, on the first performance of the revised Third Symphony]

At the first performance of the Third Symphony, 13 years previously, in the same venue, with the same orchestra (and probably many of the same listeners), Bruckner had suffered a humiliation that was surely expunged by this new reception. Anton Bruckner, just six years from his death, was at last rapturously received by an enthusiastic public.

Yet following the 1877 premiere, the critic Hanslick could write that the Third Symphony presented ‘a vision of how Beethoven’s Ninth befriends Wagner’s Walküre and finds itself under her horse’s hooves…That fraction of the audience which remained to the end consoled the composer for the flight of the rest.’

Why was Bruckner so often rejected? He was not the first composer to find critics hostile and audiences puzzled, but it is difficult to imagine how a late Romantic symphony could initially cause such antipathy and then later such respect. The fickleness of time? The ‘error’ of a naïve Bruckner declaring himself a ‘Wagnerian’ to the Brahms-loving and Wagner-hating Viennese critics? Perhaps, but even now the listening world seems divided into two camps: those who see Bruckner as the leader of symphonic music into the 20th century and those who see him on a road to nowhere: composing the same symphony nine times.

Many regard Bruckner as an influential symphonist in a way that Brahms wasn’t. It is possible to say that without Bruckner’s symphonies (and his masses) Mahler would not have been able to stretch the symphonic form both emotionally or structurally – Brahms was an apotheosis while Bruckner was a bridge into the grandness of the late-Romantic period.

Yet throughout the Third Symphony, though the listener hears the echo of both Beethoven and Wagner, and is also given a foretaste of Mahler, the influences of Brahms and even Dvorák are present as well. This is especially so in the third movement: a Slavonic-like Scherzo.

The Third Symphony, or rather the first version of the Third Symphony, was dedicated to Richard Wagner. Bruckner saw Wagner as his compositional mentor, though in many ways this is a wondrous contradiction given the pantheistic attitude of the opera composer and the devout Christianity of the symphonist. In every version of the Third there is a motif here or a theme there that could be from Tristan or Die Walküre. Bruckner is never as chromatic in his orchestral palette as Wagner, but is certainly influenced by that composer’s studied slowness of thematic development. In this present instance, Bruckner also derives such measured development from the Ninth Symphony of Beethoven (with which it shares the key of D minor) and, to a lesser degree, the Ninth of Schubert.

Possibly one of the most interesting contrasts between Wagner and Bruckner is the latter’s use of what is a relatively small orchestra – certainly smaller than Beethoven’s Ninth. No vast horn sections, cor anglais or six harps – yet Bruckner is able to elicit, through skillful orchestration, powerful fortes and startling rhythmic effects without recourse to the Wagnerian battery of brass, percussion and quadruple winds.

Structurally it is impossible to hear the beginning of the Third Symphony without being reminded instantly of the opening of Beethoven’s Ninth – the same tonal uncertainty exists. But it is through Bruckner’s different direction that we know we are at the end of the 19th century, not its early decades. The use of abrupt silences and deftly unprepared harmonic shifts announce both Bruckner’s confidence and strangeness.

The introspective nature of the second movement is created through the use of passages that echo Bruckner’s unaccompanied sacred motets. The movement concludes with the distinctly pagan ‘Sleep’ motif from Die Walküre.

The Ländler dance of the third movement Scherzo is rather madcap and, couched as it is in D minor, there is a sense of disquiet. The companion Trio, in A major, is a far simpler and almost comic excursion into the peasant lands of Bruckner’s forebears – there’s even a hint (conscious or otherwise) of the peasant dance from Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony. The structure is Classical in form, but more importantly, it serves as a template for the Mahler dances and scherzos that were to follow a decade later.

The final movement is a consummation of the themes and motives developed over the previous three movements, with chorale interjections from the horns and

vigorous sections for the whole brass section again, this time unmistakably from Die Walküre. The return of the opening theme – unexpectedly, and in D major – is a masterstroke and displays again Bruckner’s command of form and theatre.

It is, however, Bruckner’s use of motives that gives the clearest indication of Wagnerian influence. Rather than a straightforward principal melodic line, music is made through the linking of rhythmic and melodic motives and through their continual return in various guises – you don’t go out whistling the tunes from a Bruckner symphony but you may tap out a theme or two. In every movement of the Third there are clearly identifiable melodic cells, menacingly announced by the trumpet at the beginning of the first movement; surreptitiously by the strings in the third; triumphantly by the brass in the last.

So important are motives in Bruckner that they link not only internal sections within each movement, and the movements to each other, but also reappear in other works, both vocal and instrumental, across decades. This represents the differences that separated Bruckner from his peers, and the idiomatic technique that so excited and inspired the young Mahler (present at the disastrous premiere of the Third as a 17-year-old student).

The revisions that took place between the time Bruckner showed the Third to Wagner at Bayreuth in 1873, and the triumphant performance in Vienna of the truncated third version in 1890, present problems as well as delights. There is an argument put forward by some recent musicologists that the Third Symphony of 1873, seen by Wagner and never heard by Bruckner in performance, is the ‘best’ version; the other two are simply shortened and cleared of their Wagnerian quotations in the hope of wider acceptance. Others believe that the version published in 1890 and revised by both Bruckner and his pupils represents the composer’s ultimate view. Whatever the arguments, there can be no doubt that the differences which exist over the two decades of composition make the ‘Final version’ from 1889 (which we hear in this performance) a tighter and more mature work. Such a revision was surely influenced by the triumphs that came to Bruckner in the 1880s, not only in Germany, but also in the UK, the rest of Europe and the US. This shorter version, with the orchestra pared of its harp, percussion and piccolo, could also represent an ‘audience-friendly’ symphony. Neither Bruckner, nor his champions, the Schalk brothers and Ferdinand Löwe, had forgotten the debacle of 1877. Bruckner allowed changes and even compositional additions to be made by the Schalkbrothers, though Mahler was against such revisions at the time. This final version, while controversial, was sanctioned by an active, successful and authoritative composer.

Godliness, to the point of obsession, has often been a theme in discussion of Bruckner as man and composer. As with Bach and to some extent Haydn before him, Bruckner’s music making was in the service of God. His compositions, improvisations and conducting were an offering to God. The scholar Deryck Cooke puts it best when he says ‘Experiencing Bruckner’s symphonic music is more like walking around a cathedral, and taking in each aspect of it, than like setting out on a journey to some hoped-for goal.’

Perhaps this lack of worldliness, coupled with insularity and insecurity, was the basis for Anton Bruckner’s failure to be an unquestionably acclaimed composer until the close of his life. It could also be that he was the first victim of the modern concept of the composer as ‘commodity’; while ironically, the dedicatee of the Third Symphony, Richard Wagner, was the first great self-promoting success.

David Vivian Russell

Symphony Australia © 2000

First performance, original edition:

16 December 1873, Vienna. Composer conducting.

Most recent WASO performance:

18 July 1981. Albert Rosen, conductor.

Instrumentation:

two each of flutes, oboes, clarinets, bassoons; four horns, three trumpets, three trombones; timpani and strings.