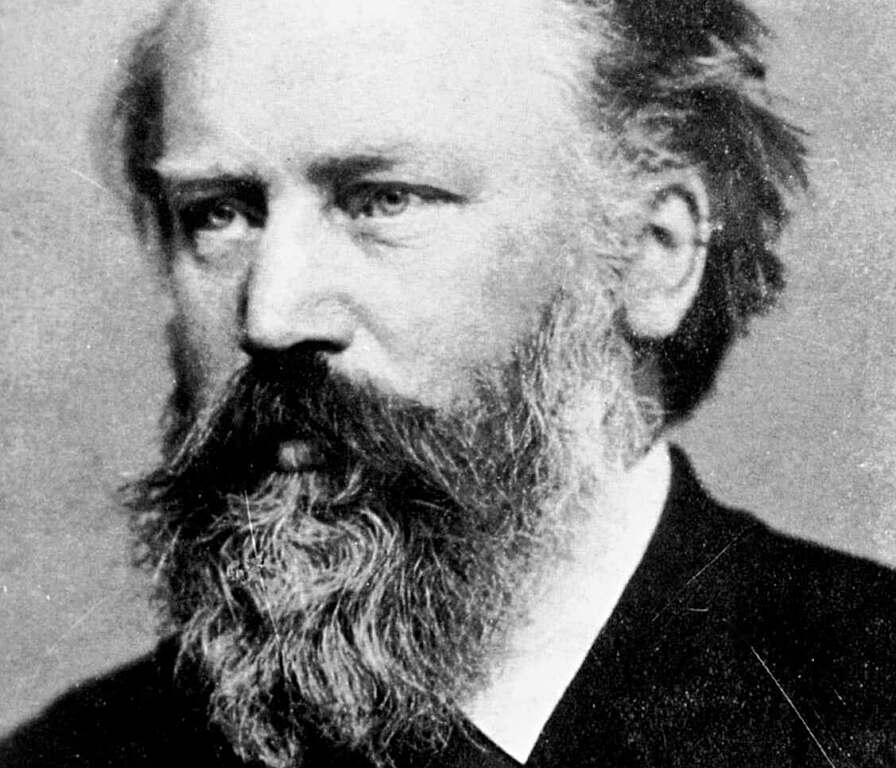

Johannes Brahms

(1833-1897)

Symphony No.3 in F, Op.90

Allegro con brio

Andante

Poco allegretto

Allegro

While the connection between Beethoven and Brahms has long been remarked, the influence of Goethe on Brahms has never been acknowledged fully. Like Brahms, Goethe was at heart a Classicist whose artistic vision was nevertheless broad enough to embrace, and indeed to be embraced by, the Romantic spirit of his age.

Perhaps because their art strived to reconcile these two conflicting impulses of passion and order, and perhaps because of the magnitude of the messages which they sought to convey, both Goethe and Brahms struggled for decades over their greatest masterpieces. In Brahms’ case, the breakthrough First Symphony took 15 years of painstaking effort. For Goethe, Faust emerged only after 60 years of intermittent rejection and revision. So perhaps it should be no surprise that when Brahms sought to convey his most personal thoughts through music, he turned to Goethe for his texts.

So too the middle movements of the Third Symphony emerged (according to Max Kalbeck) from incidental music which Brahms had sketched (but apparently never used) for a production of Goethe’s Faust. While no obvious traces of this appear in the Third Symphony, the dramatic power and universalist vision embodied within it suggest that no ordinary motivations were behind its composition.

Brahms began formal work on the Third Symphony during 1882 and completed it in Wiesbaden in 1883, when he was 50 years old. He had moved to Wiesbaden primarily to be near the contralto Hermine Spies, and it seems that she was the latest in a longish line of female idols whom Brahms wished to marry but didn’t dare ask.

Brahms’ unrequited love for Hermine was exacerbated by other personal crises at this time – not least the recent death of his revered teacher Eduard Marxsen and a temporary estrangement from Joseph Joachim. Small wonder then that the sunny disposition of the Second Symphony gave way now to more mixed emotions.

The symphony’s first performance was given by the Vienna Philharmonic under Hans Richter in December 1883, and was well received on first hearing. It has never really fallen out of favour, owing to its mastery of construction, its persuasive blend of lyricism and drama, and its exceptional orchestration. Apparently during the first rehearsals Brahms made many minor adjustments to the instrumental arrangements, subtly altering the orchestral colouring. And the resulting work, with its extraordinary clarity of instrumental effects and chamber music textures, demonstrates that Brahms was a much underrated orchestrator.

He was even better at providing spectacular openings for his symphonies, and the Third is no exception. It begins with three dramatic chords which immediately give way to the passionate main theme in the strings. As in so much of Brahms’ greatest music, the first 30 seconds have penetrated directly into the heart of the musical matter and the sound-world of the entire symphony has largely been established. After the graceful secondary theme appears in the clarinet, the development is followed by the return of the opening motif in the horns, leading to an unusually diverse recapitulation and a coda which brings a more tranquil restatement of the opening material.

The slow movement contains one of Brahms’ most famous melodies which is introduced by the clarinet and then imitated by the violas and other sections of the orchestra. It is music which is so evocative that it lends itself to a variety of conflicting interpretations – it is chorale-like but also pastoral, its grace is Mozartian but its reflectiveness is typically Brahmsian, it is almost naive in sentiment but extraordinarily sophisticated in execution, and its musical material is basically diatonic but with interjections of wrong-key ‘foreign’ chords.

The third movement serves as a kind of melancholy minuet and trio. The minuet opens in the cellos and, after a brief trio section, it returns with the horn leading the way.

As in his other symphonies, Brahms throws the weight back on in the finale. It begins sotto voce and with a sense of suppressed agitation but soon boils over, the blaring brass and woodwind working up to a climax during the development. In the recapitulation the tempo slows and at last, in pianissimo whispers in the strings, the very first theme of the symphony returns, and consolation takes over from conflict as this most unified and beautifully proportioned of symphonies ushers in its sublime conclusion. Had he lived to hear it, Goethe may well have been impressed.

Adapted from a note by Martin Buzacott

Symphony Australia © 1997

First performance:

2 December 1883, Vienna. Hans Richter conducting.

Most recent WASO performance:

28 August 2015. Asher Fisch, conductor.

Instrumentation:

two each of flutes, oboes, clarinets, bassoons and contrabassoon; four horns, two trumpets, three trombones; timpani and strings.