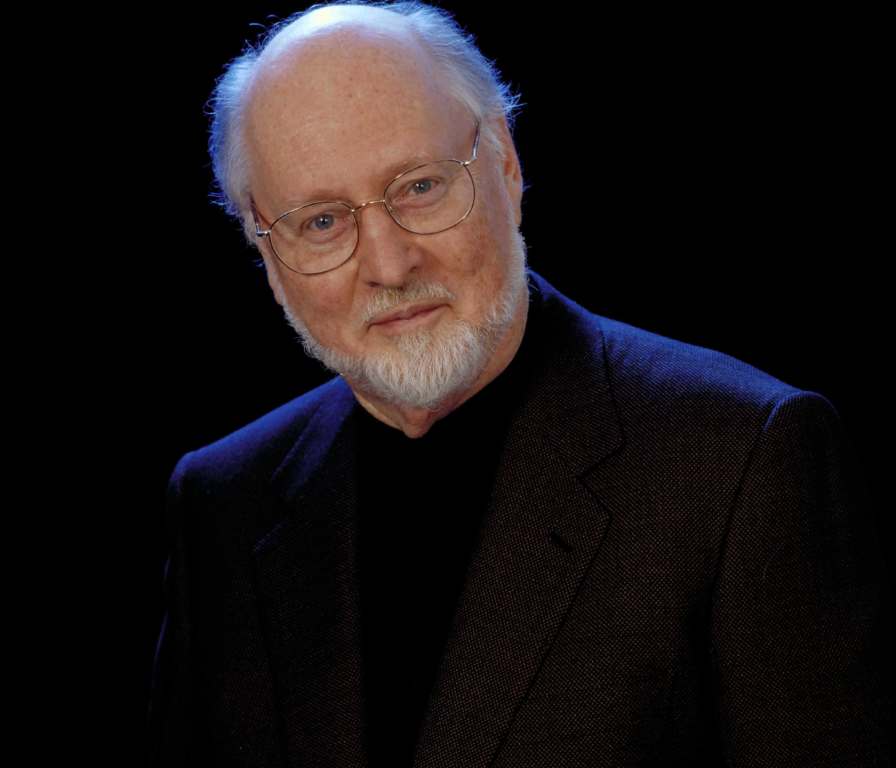

The statistics speak for themselves: five Academy Awards, over 50 Oscar nominations, and a score which in 2005 topped the American Film Institute’s list of the 25 greatest film scores of the century (Star Wars). John Williams is justly famous for his sweeping, richly scored themes, but the breadth of his screen output shows that he is proficient in almost every genre of symphonic cinematic scoring.

The eclecticism that characterises his music is largely a result of his background and training. Born the son of a jazz drummer (Johnny Williams Snr played for CBS Radio and Columbia Pictures), he was exposed to the rigours of professional musical life from an early age. Williams spent hours watching his father work and credits this with fostering a fascination with orchestral textures. Formal music studies in California were followed by a stint in the US Air Force, where he composed and arranged for military bands. On being discharged, he moved to New York where he studied piano at Juilliard and picked up work as a jazz pianist and arranger.

Williams subsequently returned to Los Angeles, where his sight-reading abilities earned him a job as a pianist with Columbia Studios. He had no particular interest in film music at this point but a chance opportunity resulted in arranging work, which he eagerly accepted. It was during his next job, however, working at Universal under Alfred Newman and Bernard Herrmann, that Williams really served his apprenticeship and developed the kind of musicianship and work ethic that would make him one of Hollywood’s most prolific and versatile film composers. Under the terms of his seven-year contract he had to write the music for 39-40 one-hour television shows per year – on average one every week. For this he had to hop between genres – one week a comedy, the next a western, the following a space opera. ‘I was not selective,’ he says. ‘I would do whatever I was given and had no idea it would lead to being a film composer.’ However, that it did, and it was his scores for the films The Reivers and The Cowboys that caught the ear of the 27-year-old Steven Spielberg, who asked him to score his debut feature, The Sugarland Express (1974). Thus began an artistic partnership that has endured for almost 50 years. Williams’ collaborations with Spielberg and George Lucas have resulted in his most successful scores, and have led to his being credited with restoring the symphonic component to the modern film score.

What is it about Williams’ movie themes that makes them so memorable? That he has a melodic gift is undeniable; his extensive musicianship is not in question. His real genius, however, lies in his ability to devise a seemingly simple theme, perhaps consisting of a mere few notes, with which he is able to extract the full dramatic essence of a story or character. Moreover, he is able to convey this essence to the viewer using musical language that resonates instantaneously. Williams was aware of Spielberg’s and Lucas’ desire to recapture the romanticism and excitement of the black-and-white movies and action serials of their childhood, and so he mined his by now extensive film composer’s arsenal to create a fitting musical accompaniment.

His psychological and dramatic insights aren’t confined to the action-adventure blockbuster, however. In Jaws, the jaunty sea shanty introduced by woodwind as Quint, Brody and Hooper set out to sea gives way to the flight and chase of a fugue in the strings as the hunters become the hunted. In Hook, the magical strains of the celeste and glockenspiel glistening atop orchestral triplets transport us to Neverland. Such is Williams’ reputation that he can attract some of the most respected names in classical music to collaborate on his projects, including Yo-Yo Ma, Renée Fleming and Itzhak Perlman, the latter having played the haunting violin solo in the theme from Schindler’s List. So unerring are his dramatic instincts that Spielberg credits Williams with making him a ‘better director than I could ever have been without him’.

The esteem in which Spielberg holds the composer is best summed up by an anecdote related by Williams himself, who tells of being so moved by the initial screening of Schindler’s List that he had to step outside to compose himself. When he expressed the concern that he didn’t think he could do it and that perhaps Spielberg should find another composer, the latter replied, ‘I know, but they’re all dead.’ Among film’s greatest composers, for Steven Spielberg at least, John Williams is the last man standing.

Adapted from a note by Lorraine Neilson

Symphony Services International © 2014/2017