Gustav Mahler

(1860-1911)

Symphony No.3 in D minor

Part I

Kräftig. Entschieden [Vigorous, decisive]

Part II

Tempo di menuetto. Sehr mässig [Very moderately]

Comodo. Scherzando. Ohne Hast [Without haste]

Sehr langsam. Misterioso [Very slowly, mysteriously] –

Lustig im tempo und keck im Ausdruck [Lively in tempo and jaunty in expression] –

Langsam. Ruhevoll. Empfunden [Slowly, with serenity, expressively]

The world of Symphony No.3

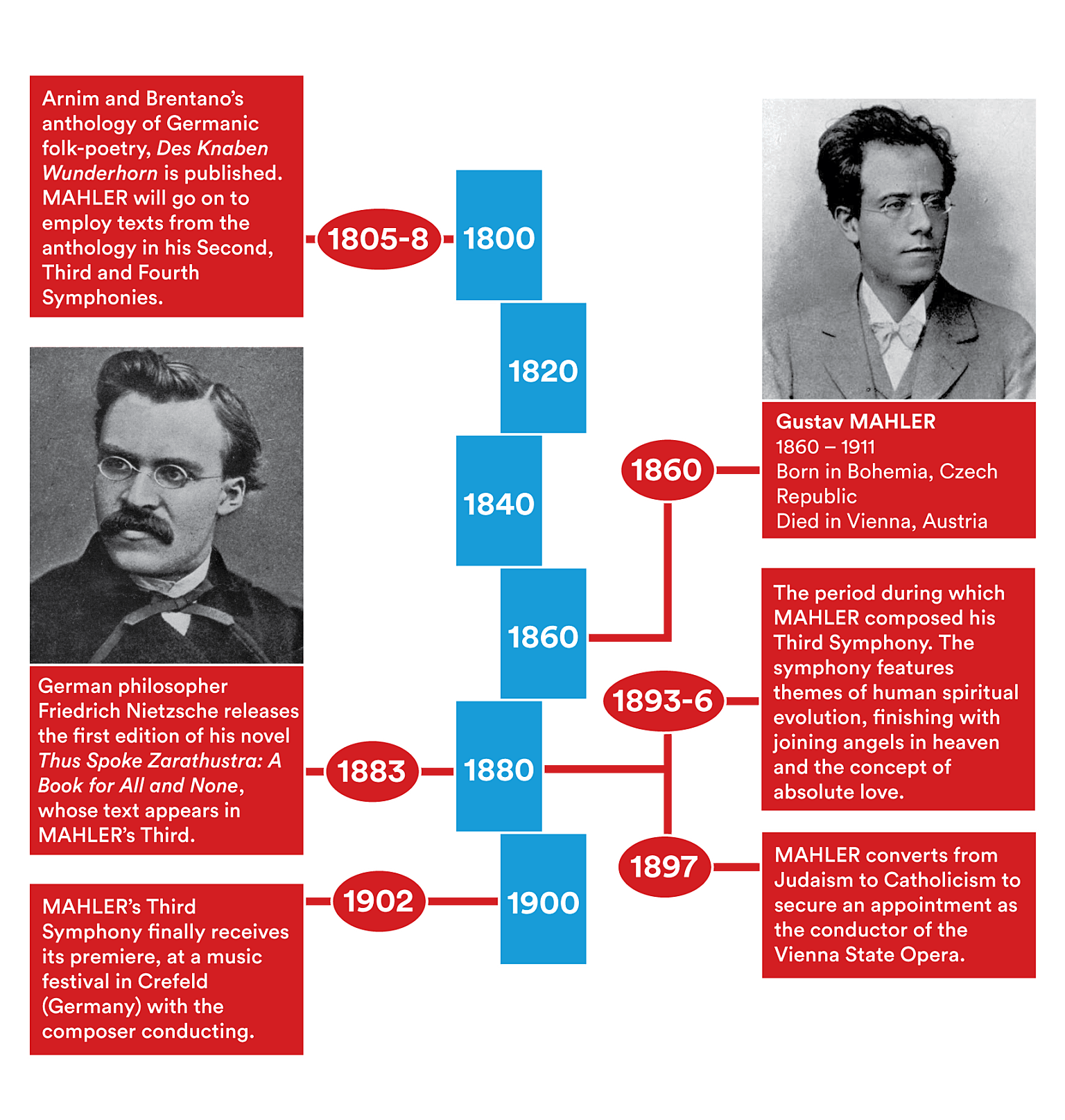

Mahler’s Second, Third and Fourth Symphonies form a trilogy depicting the composer’s search for spiritual meaning in a tragi-comic universe. Each of them employs texts from Des Knaben Wunderhorn (The Youth’s Magic Horn), Arnim and Brentano’s anthology of Germanic folk-poetry published in 1805-08, and lunges back and forth between the most profound philosophical insights and absurd banality, as they attempt to achieve Mahler’s symphonic ambition of ‘embracing the world’.

Dating from the 1890s, they were all composed at a time of great spiritual uncertainty, both for Mahler himself and for European society in general. Reflecting the broader cultural trends, that final decade of the 19th century was a time of innovation and anxiety in the arts. The Expressionist movement in the visual arts and drama was at its height, and in music the young Arnold Schoenberg was just beginning to push the boundaries of tonal harmony.

Dreams and the role of the unconscious became means of establishing a higher truth within the arts. And as reality and the world of illusion collided (in Frank Wedekind’s play Spring Awakening a character appears carrying his head under his arm), nightmare visions became mixed-up with nostalgic reminiscences of innocence. Death became the only philosophical certainty.

Owing to his personal circumstances, Mahler keenly felt the psychological and spiritual crises of the Zeitgeist. The second of 12 children, as a child he witnessed the death in infancy of five of his brothers and sisters. He grew up treating every moment as if it were his last, terrorised those who wasted his time, and was relentless in his quest to discover a greater order within the universe.

Born a Jew, he converted to Catholicism around the time the Third Symphony was completed. While this conversion was ostensibly to secure his conducting post at the Vienna State Opera, there is no doubt that in later years Mahler became genuinely attracted to the fundamental principles of Christian mysticism. All his life he was plagued by spiritual doubt and a fear of death. Like so many of his scores, Mahler’s Second, Third and Fourth Symphonies contain all the symptoms of his anxieties – the death-obsession and the paradoxical but understandable celebrations of life and the innocence of childhood, the virtual worship of nature, and the desire to depict all human experience within the confines of the symphonic form. Within the Third Symphony, these ambitions are encapsulated in a massive journey which effectively retraces human spiritual evolution, beginning deep in the primeval dust, working its way up through vegetation and the animal world, on to humanity and then finally up to the angels and heaven, existing within the broader category of absolute love.

It’s no small ambition, which is why the Third Symphony takes more than an hour and a half to perform. (The symphony was going to be even longer, but Mahler removed the seventh and final movement, saving it for the finale of his Fourth Symphony instead.)

Writing the symphony

Mahler never felt comfortable with ‘programs’ being attributed to his nine symphonies, but he was his own worst enemy in this regard. To maintain intellectual control of the massive architecture of the symphonies, he himself often created ‘programs’ which he described in detail to friends. Then, when the works came to be published, he removed the programs and denied that they had any role to play in audiences’ appreciation of the music.

Perhaps because of its size, the Third Symphony received more in-depth programmatic analysis by Mahler than any of his other works. It went through countless changes of title and subtitle: Pan, The Happy Life, The Happy Science, My Happy Science, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, A Midsummer Noonday’s Dream, and A Summer Morning Dream, and so on. In the end, he chose Symphony No.3 in D minor.

But even that uncomplicated title failed to satisfy him. He wrote to Natalie Bauer-Lechner, ‘Calling it a symphony is actually incorrect because in no way does it adhere to the usual form. But, in my opinion, creating a symphony means to construct a world with all manner of techniques available. The constantly new and changing content determines its own form.’

Aside from the overall title, each of the movements also went through name and program changes. Mahler wrote to Friedrich Löhr at the end of August 1895 telling him: ‘My new symphony…is all in large symphonic form. The emphasis on my personal emotional life (in the form of “what things tell me”) is appropriate to the work’s singular intellectual content.’ He then went on to characterise the movements:

1. Pan awakes – Summer marches in

2. What the flowers in the meadow tell me

3. What the beasts in the wood tell me

4. What Man tells me

5. What the angels tell me

6. What love tells me

None of these descriptive titles would end up in the published score. As Mahler himself said, ‘Just as it seems trivial to me to invent music to a preconceived program, I find it unsatisfactory and sterile to add one to an existing musical composition; notwithstanding the fact that the creative urge for a musical organism certainly springs from an experience of its author.’ In other words, Mahler knew that whatever its origins in personal experience, and whatever its ability to create spiritual exaltation, music ultimately remained an abstract construct.

Mahler may have begun working on the Third Symphony as early as 1892. In typical fashion he worked backwards on it, completing the first movement last.

Movements two to six, together with some sketches for the first, were written during the summer of 1895 in Steinbach – his Alpine retreat near Salzburg, where he found peace after winter seasons as musical director of the Hamburg Opera.

Opera commitments in Hamburg also kept him from completing the first movement until the following summer of 1896, when once more he returned to Steinbach. But unfortunately he’d left the sketches for the first movement behind. So he sent an urgent letter to a friend to break into his Hamburg apartment and retrieve the sketches, which were duly delivered to him. ‘To you those few sheets of music must have seemed quite unimportant,’ he wrote thanking his friend, ‘but in fact they contained (according to my way of sketching) all the seeds for the now fully grown tree.’ Once in possession of those few pages of sketches, Mahler completed the massive 40-minute first movement in just a few weeks.

The symphony’s final structure is bizarre. It is effectively divided into two parts. The gargantuan first movement forms the first part and the final five movements the second. That first movement itself, however, is a combination of two individual movements (the difference in tone is still evident), while the final three movements run on without a break, before ending, unusually, with a slow movement.

There had been precedents of course – Tchaikovsky’s Pathétique Symphony also ends with a slow movement, and many previous symphonies had run their movements into each other. But no one had ever previously conceived a symphony on such a grand scale and with such an apparent disregard for traditional symphonic form.

Not only the form, but the orchestra too was inflated - four flutes, four oboes (plus cor anglais), five clarinets with bass clarinet, four bassoons (plus contrabassoon), eight horns, four trumpets, four trombones with tuba, two harps, a myriad of percussion, large forces of strings to balance them all, not to mention a solo contralto, and choirs of women and boys. Small wonder that it took some years before the work was first performed in its entirety. While Artur Nikisch and Felix Weingartner conducted individual movements of the work soon after its completion, the complete work was first performed at a music festival in Crefeld only in 1902, with Mahler himself conducting. And it took much longer than that for it to reach the ‘outside’ world (only being premiered in England in 1961 and Australia in 1967). But then Mahler always did say that it would be some time before his music was understood.

The symphony – musical analysis

The Third is a ‘nature’ symphony. Shortly after its completion, the conductor Bruno Walter visited Mahler at Steinbach. As Walter gazed at the magnificent Alpine scenery Mahler told him, ‘No need to look. I have composed all this already.’ The opening movement is Mahler’s own ‘rite of spring’, composed nearly two decades before Stravinsky’s masterpiece. As he was composing it, Mahler wrote to Natalie Bauer-Lechner: ‘This almost ceases to be music, containing mostly sounds from nature. And it is eerie how from lifeless matter…life gradually breaks forth, developing step by step into ever-higher forms of life.’ In another context he wrote, ‘Here it is the world, nature as a whole, that is awakened out of unfathomable

silence and sings and rings.’

Nature’s singing and ringing begins with a call to attention by the eight horns, and indeed the opening minutes of the symphony are decidedly ‘brass-heavy’, with trombones and tuba depicting the darkness before the arrival of life on earth. Of course it wouldn’t be a largescale Mahler movement if it didn’t have a marching band thrown in – and here one duly appears, as if emerging unconcerned from the prehistoric swamp.

This is summer coming in, and its arrival corresponds with what would be regarded as ‘the opening Allegro proper’ in a traditional symphony. It’s such a massive movement, both in size and spiritual concerns, that Mahler said he was grateful he composed it last, because if he hadn’t, he would never have dared to finish the symphony as a whole! In the score, he directed that there should be a long pause following its conclusion, clearly delineating the end of the first part of the symphony.

The second part of the symphony begins a world away from the first – purportedly with the flowers in the meadow, but musically very much within the confines of Viennese salons, not to mention in a similar sound-world to parts of the Fourth Symphony. For the listener, this second movement comes as quite a shock. But that in itself says a lot about the invigorating effect of Mahler’s music, for this otherwise innocuous little minuet remains somehow disturbing and unsettling in the context in which it appears.

Undoubtedly it was inspired in part by the summer displays of flowers in the meadows outside Mahler’s workroom in Steinbach (to which he referred in correspondence). But Mahler never just saw the beauty of nature divorced from its terror. As he himself wrote: ‘Suddenly a stormy wind blows across the meadow and shakes the leaves and flowers, which whimper and moan on their stems as if begging for salvation.’

The third movement (in the world of animals now, according to Mahler’s correspondence) introduces an instrumental version of Mahler’s setting of ‘Ablösung im Sommer’ (Relief in Summer) from Des Knaben Wunderhorn. Opening with a jaunty little wind melody over pizzicato accompaniment in the strings, it forms a kind of scherzo and trio. Again, it’s superficially happy and playful. But the\ darkness (and the minor tonality) is never far away. The trio section is famous for its beautiful solo for posthorn, an unusual brass instrument which lends its name to Mozart’s Serenade K.320. The dancing and play resume, but towards its end the movement relapses violently into the eerie, unformed sound-world of the symphony’s opening. Nothing remains unchallenged in Mahler’s world.

The final three movements then proceedwithout a break. The first of these (i.e. the fourth) introduces the human element – and the human voice itself. There is a rapt stillness marking the contralto’s entry, as if humanity is rising from the ashes. The text is from Nietzsche’s Also sprach Zarathustra.

O Mensch, gib Acht!

Was spricht die tiefe Mitternacht?

Ich schlief! Aus tiefem Traum bin ich erwacht!

Die Welt ist tief!

Und tiefer, als der Tag gedacht!

Tief ist ihr Weh!

Lust tiefer noch als Herzeleid!

Weh spricht: Vergeh!

Doch alle Lust will Ewigkeit,

Will tiefe, tiefe Ewigkeit.

O Man, take heed!

What does the deep midnight say?

I slept. From deep dreaming I was wakened!

The world is deep,

And deeper than the day imagined!

Deep is its grief!

Longing, deeper still than heartache!

Grief says: Go hence!

But all longing craves eternity,

Craves deep, deep eternity.

We know from his correspondence that Mahler had read Nietzschequite extensively – indeed one of the symphony’s original titles, The Happy Science, derived from him. But later in his life Mahler declared himself an opponent of Nietzsche’s godless philosophy. In any case, in this ever-so-slow slow movement he gives us one of his most sublime creations – a world where time stands still.

After a return to the deep bass of the opening, the fifth movement then enters with astonishing contrast, marked by the voices of boys, the sound of bells and woodwind, and the setting of another poem from the Wunderhorn collection.

Es sungen drei Engel einen süssen Gesang;

Mit Freuden es selig in dem Himmel klang,

Sie jauchzten fröhlich auch dabei,

Dass Petrus sei von Sünden frei,

Und als der Herr Jesus zu Tische sass,

Mit seinen zwölf Jüngern das Abendmahl ass:

Da sprech der Herr Jesus: Was stehst du denn hier?

Wenn ich dich anseh’, so weinest du mir!

Und sollt’ ich nicht weinen, du gütiger Gott,

Ich hab’ übertreten die zehn Gebot.

Ich gehe une weine ja bitterlich.

Ach komm und erbarme dich über mich!

Hast du denn übertreten die zehen Gebot,

So fall auf die Kniee und bete zu Gott!

Liebe nur Gott in alle Zeit!

So wirst du erlangen die himmlische Freud’.

Die himmlische Freud’ ist eine selige Stadt,

Die himmlische Freud’, die kein Ende mehr hat!

Die himmlische Freude war Petro bereit’t,

Durch Jesum und Allen zur Seligkeit.

Three angels were singing a sweet song,

With blessing and joy it rang in Heaven,

They shouted for joy, too,

That Peter was set free from sin.

And as the Lord Jesus sat at table,

With his twelve disciples at the evening meal,

Lord Jesus said: ‘Why stand you here?

When I look at you, you weep before me.’

‘And should I not weep, thou God of goodness,

I have broken the ten commandments.

I go my way and weep bitterly,

Ah, come and have mercy on me!’

‘If you have broken the ten commandments

Then fall on your knee and pray to God,

Love only God for all time!

So you will attain heavenly joy.’

Heavenly joy is a blessed city,

Heavenly joy, that knows no end!

Heavenly joy was granted to Peter,

Through Jesus, and for the delight of all.

It’s a radiant sound, soon joined by choral and solo women’s voices, harps, horns and trumpets. Those who know the Fourth Symphony will instantly recognise the descending melody from the soprano’s solo at the end of that symphony. This was how Mahler imagined Heaven.

And then at last, as we head toward the hour-and-a-half mark, the finale emerges. Mahler wrote: ‘It is the zenith, the highest level from which the world can be viewed. I could also name the movement something like “What God tells me”, in the sense that God can only be comprehended as “Love”.’

It’s a magnificent slow movement with strings carrying the broad, achingly poignant melody, and solo wind instruments later taking it over. Mahler based the movement on the words of Christian reconciliation and forgiveness – ‘Father, look on these my wounds – let not one creature be lost!’

The movement proceeds as a series of variations which occasionally touch on the drama of the symphony’s opening, but ultimately lead to a climax in which fear is confronted with a steadfast faith. And here, at last, faith triumphs, and an absolute love wins out over all that would dare to destroy it.

Martin Buzacott © 1998

First performance:

9 June 1902, Krefeld. Composer conducting.

Most recent WASO performance:

12 & 13 October 2007. Oleg Caetani, conductor. Nancy Maultsby, mezzo soprano.

Instrumentation:

four flutes (all also piccolo), four oboes (4th also cor anglais), two E-flat clarinets (2nd also 4th clarinet), three clarinets (3rd also bass clarinet) and four bassoons (3rd and 4th also contrabassoon); eight horns, four trumpets, four trombones and tuba; two timpani, five percussion, two harps and strings. Off-stage Instruments: posthorn (3rd mvt), snare drums (1st mvt), six tuned bells (5th mvt).