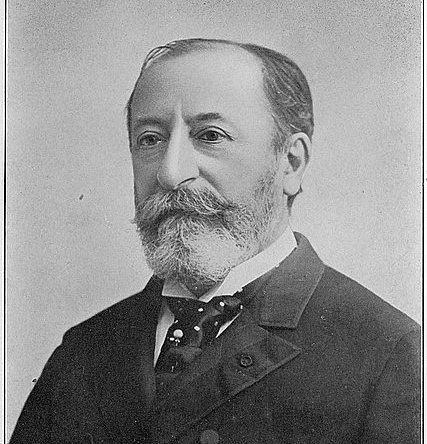

Camille Saint-Saëns

(1835-1921)

Symphony No.3 in C minor, Op.78 ‘Organ’

I Adagio – Allegro moderato – Poco adagio

II Allegro moderato – Presto – Maestoso – Allegro

Saint-Saëns was something of an Anglophile. So it was a happy coincidence that when he was making plans for another symphony, the Royal Philharmonic Society invited him to perform as both conductor and pianist at one of its London concerts. As the non-profit Society could not afford the requested fee of £40, they suggested £30, plus a formal commission to write the Third Symphony under the Society’s auspices.

Saint-Saëns agreed and immediately began work on the symphony, saying to the Society: ‘It will be terrifying, I warn you.’ And he wasn’t wrong. Considering the Society’s financial state at the time, the prospect of an outsize orchestra complete with organ and multiple pianists must have struck fear into the heart of at least the treasurer.

And as the blood pressure of Society members rose, so too did the key of the symphony. ‘This imp of a symphony has gone up a half-tone; it didn’t want to stay in B minor and is now in C minor,’ Saint-Saëns advised the long-suffering Society members as he worked on the ever-expanding piece.

In the end, Saint-Saëns came up with a symphony in two parts, but still more or less using the traditional four movements. The first part consists of an Allegro and Adagio, corresponding to conventional first and second movements, and the second part is a scherzo and finale merged into one. The use of the organ was inspired by Liszt’s employment of it in his symphonic poem Hunnenschlacht (Battle of the Huns) and the published version of the Organ Symphony is dedicated ‘to the memory of Franz Liszt’, who had died shortly after the premiere.

That premiere occurred on 19 May 1886 in St James’s Hall, London, with the composer conducting, as well as appearing as soloist in his own Fourth Piano Concerto. On the whole, the reception was excellent, despite the best efforts of a few Wagnerians in the audience. Afterwards, the great admirer of British royalty was introduced to the Prince of Wales (the future King Edward VII). A Paris premiere, the following year, was a great success and prompted Charles Gounod to proclaim, ‘There goes the French Beethoven.’

Saint-Saëns summarised the symphony by saying, ‘I have given all that I had to give…What I have done I shall never do again.’ And he was as good as his word. The Organ Symphony was to remain his supreme achievement in music and it is still one of his most frequently performed works. In recent years it has achieved a certain popular success, following its quotation in the soundtracks for the movies Babe and Babe: Pig in the City.

Saint-Saëns was a virtuoso by nature. Indeed, the ongoing criticism of his music has been that his prodigious technical facility and ability to dazzle sometimes distract from the greater impact of the music itself. Certainly in the Organ Symphony Saint-Saëns gives literal meaning to the cliché ‘pulling out all stops’. While much of the organ writing is subtle, even understated, climaxes are marked by thunderous passages for the organ, and deliberately grandiose scoring.

The ‘first movement’ develops through a kind of Lisztian transformation of themes, whereby the thematic material appears in a series of varying guises rather than being developed in a strictly Classical sense. After the ‘first movement’ has led without pause into the ‘second’, the organ enters, surprisingly discreetly, as an accompaniment to the mystical main theme, marked Poco adagio. The scherzo (‘third movement’) begins the second half of the piece, and much of its thematic material derives – albeit vastly transformed – from the preceding Adagio. From here Saint-Saëns introduces all the fireworks he can. The tempo increases to Presto, the orchestration becomes more vibrant and new themes are superimposed over the existing ones, before the organ almost lunges into the finale.

This concluding section is a good example of the differing value-judgements which Saint-Saëns’ music invites. The climax builds through fanfares, four-hand piano figures, loud organ chords and extensive fugal writing, carrying the work through to its triumphant conclusion. Depending on one’s viewpoint, Saint-Saëns either demonstrates his unrivalled compositional virtuosity, or simply goes over the top. However, no one can doubt that the Organ Symphony has demonstrated its enduring appeal.

Martin Buzacott

© Symphony Australia

First performance:

19 May 1886, London. Saint-Saëns, conductor.

First WASO performance:

13 May 1971. Tibor Paul, conductor.

Most recent WASO performance:

15 & 16 November 2019, Lionel Bringuier, conductor.

Instrumentation:

three flutes (third doubling piccolo), two oboes and cor anglais, two clarinets and bass clarinet, two bassoons and contrabassoon; four horns, three trumpets, three trombones and tuba; timpani and percussion; organ, piano four hands; strings.