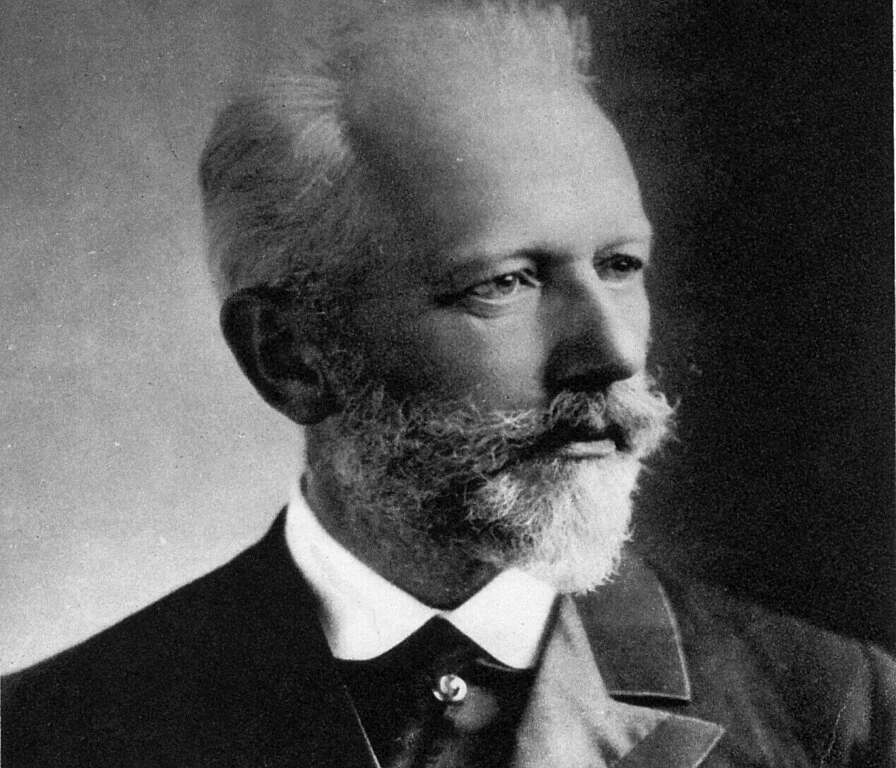

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840 – 1893)

Symphony No.6 in B minor, Op.74, Pathétique

Adagio – Allegro non troppo

Allegro con grazia

Allegro molto vivace

Finale (Adagio lamentoso – Andante)

The original audience for the Sixth Symphony was uncomprehending and ambivalent. Tchaikovsky had expected this, writing to his nephew and the dedicatee, ‘Bob’ Davidov, that he wouldn’t be surprised if the symphony were ‘torn to pieces’, even though he considered it his best and most sincere work. The critic Hermann Laroche suggested that audiences who ‘did not get to the core’ of the symphony would ‘in the end, come to love it’. As it turned out, it took them only 12 days. In the intervening period its composer had died, and for the second performance, in a memorial concert, it was promoted with the composer’s subtitle: Pathétique (or Pateticheskaia Simfoniia – ‘impassioned symphony’ – as he had conceived it in Russian). The symphony was declared a masterpiece.

The myth of the-Pathétique-as-suicidenote (not to mention Tchaikovsky’s ‘suicide’ itself) has been more or less debunked in the past two decades. There are no grounds for doubting that Tchaikovsky died from post-choleric complications; the ‘court of honour’ theory has been undermined; and his social, financial and artistic situation all speak against any other motivation for suicide, even if he continued to be troubled by his homosexuality. The Sixth Symphony, specifically, seems to have been a source of immense pride, satisfaction and joy to him. And shortly after its premiere he’s reported to have said, ‘I feel I shall live a long time.’

He was wrong. His audience, now in mourning and seeking ‘portents’, immediately heard the Sixth Symphony (the Pathétique) in a new way. New significance was given to the appearance in the first movement of an Orthodox burial chant, ‘Repose the Soul’ – a hymn sung only when someone has died – and to the otherworldly, dying character of the adagio finale.

Even if the symphony is not a suicide note, there is a programmatic and semi-autobiographical underpinning that is the source of its unusual form and turbulent emotions. Tchaikovsky admitted the existence of a program but was cagey about the details, perhaps because it reflected his romantic feelings for Davidov. The closest we have is a sketched scenario, devised originally for an abandoned symphony in E flat but appearing to correspond with much of the Sixth Symphony:

Following is essence of plan for a symphony Life! First movement – all impulse, confidence, thirst for activity. Must be short (Finale death – result of collapse). Second movement love; third disappointment; fourth ends with a dying away (also short).

There are aspects of this program and the Sixth Symphony that suggest suffering, but for Tchaikovsky the composition of the symphony was a cathartic experience rather than an expression of current sufferings. He himself wrote: ‘Anyone who believes that the creative person is capable of expressing what he feels out of a momentary effect aided by the means of art is mistaken. Melancholy as well as joyous feelings can always be expressive only out of the Retrospective.’

In its art this is Tchaikovsky’s most innovative symphony. He dares to conclude with a brooding slow movement and uses boldly dramatic gestures to give the music its emotional impulse. The ‘limping’ elegance of the second movement waltz would have been less surprising, to Russians at least – its five-beat metre was a part of a tradition that was embraced by Borodin, Rimsky-Korsakov and Mussorgsky (in his Pictures at an Exhibition), and later Rachmaninov (in The Isle of the Dead).

In the Sixth Symphony Tchaikovsky comes to terms with his professed inadequacies in structural matters. His solution in the first movement was to extend the exposition section, so well suited to his melodic gifts, and to compress the development section in which he felt his skills inadequate. The music begins in the depths with the dark colour of the bassoon and yet somehow Tchaikovsky sustains a downward trajectory, or the impression of one, for the whole work.

In the third movement the idea of ‘disappointment’ is replaced by something more malevolent. In purely musical terms it conflates two musical figures – feverish tarantella triplets and a spiky march – but the juxtapositions and incursions into each other’s thematic territory create a disturbing sense of antagonism. The movement’s applause-provoking conclusion could be triumphant, or it could be the crash of self-delusion.

The finale may not fit the formula established by Tchaikovsky’s classical predecessors, but within the emotional journey of the symphony its stark sense of tragedy provides an inevitable conclusion – all the more powerful for the grace and jauntiness of the preceding movements.

Yvonne Frindle © 2008

First performance:

28 October 1893, St Petersburg. Tchaikovsky, conductor.

First WASO performance:

19 September 1942. E.J. Roberts, conductor.

Most recent WASO performance:

3-4 June 2016. Daniel Blendulf, conductor.

Instrumentation:

three flutes (third doubling piccolo), two oboes, two clarinets, bass clarinet, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion and strings.