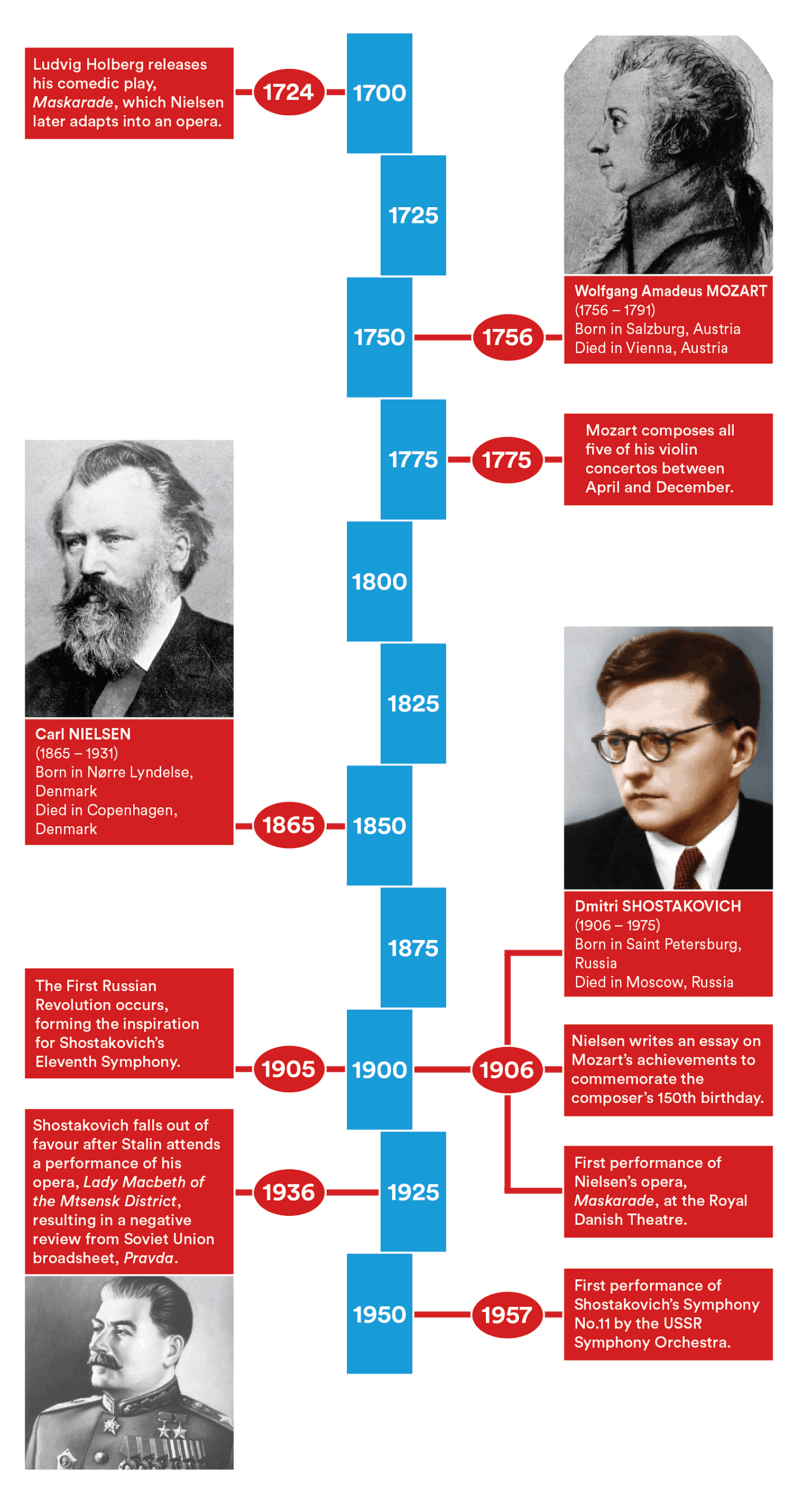

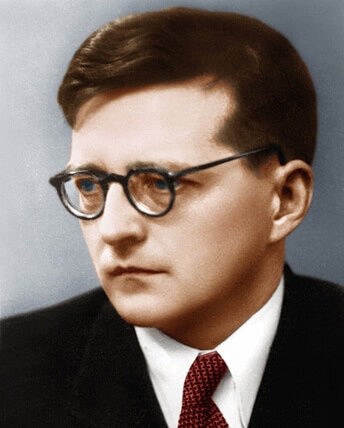

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906–1975)

Symphony No.11 in G minor, Op.103 The Year 1905

Adagio (Palace Square) –

Allegro – Adagio – Allegro (Ninth of January) –

Adagio (Eternal Memory) –

Allegro non troppo (The Tocsin)

On Sunday 9 January 1905 (22 January in the Western calendar), thousands of workers together with their families came to present a petition to Tsar Nicholas II at the Winter Palace in St Petersburg. A priest led the procession, whose purpose was to request an amnesty for political prisoners, a Constituent Assembly, and an eighthour working day. The Tsar was not there; the procession was met with gunfire and cavalry charges, which killed and injured hundreds, setting the stage for the October Revolution of 1917.

Shostakovich grew up in the shadow of the 1905 uprising, and many of his formative memories (if the controversial memoirs Testimony are to be believed) seem to have been of the turmoil of the following years. Again, however, if Testimony is to be believed, the Symphony No.11 (1957) should be seen against a rather different background.

In 1956, Nikita Khrushchev made a speech to the Twentieth Party Congress denouncing Stalin. Both Poland and Hungary sought looser ties with Russia as a result, with Hungary demanding political liberalisation. The ideological ‘thaw’ of the period after Stalin’s death in 1953 also had its effects in the arts. Many artists who had been denounced by Andrei Zhdanov at the 1948 Communist Party tribunal were rehabilitated around this time, with Shostakovich releasing many works he had composed but thought it imprudent to publish. Demonstrators pulled down Stalin’s statue in Budapest, and many popular demands were met; however, when Hungary announced its intention to withdraw from the Warsaw Pact, Russian tanks were sent into Budapest within a few days. Around 20,000 Hungarians were killed, and 200,000 fled to the West.

In 1957, Shostakovich composed his Symphony No.11. With the 40th anniversary of the October Revolution approaching, he chose a revolutionary subject for his new work. What he meant by the choice of a subject bearing such a clear parallel to recent events, is – like virtually everything concerning the inner motivation of his music – uncertain. Even the most experienced scholars of Shostakovich’s music have no more than the historical background, some memoirs of disputed provenance, and the music itself to study. Listeners can thus form their own conclusions, although many recent scholars are fond of doing that for us.

The symphony as a whole is so overtly programmatic that it is tempting (and not difficult) to assign concrete associations to every musical event which occurs. Thus, the opening ‘is’ the square of the Winter Palace at dawn on the morning of Bloody Sunday; the ominous motif given out by the timpani at the close of the strings’ opening paragraph ‘is’ the crowd; the trumpet solo shortly after ‘is’ the warning given by the Tsar’s soldiers before opening fire. The danger here is that the symphony itself would then be as unsubtle as that program. All these motifs assume other roles during the course of the work, sometimes in musical contexts difficult to match with their presumed associations. No less than in Wagner’s operas (for example), the musical motifs here are flexible enough to sustain purely symphonic development.

There is thus much musical subtlety that over-reliance on the program would cause us to miss. The strings’ opening music features a wealth of harmonic variety which we are in danger of not noticing, if we simply see it as a depiction of a Palace Square at dawn. Occasionally it even becomes programmatic beyond its presumed role. Within a few pages it acquires the repeated notes characteristic of Orthodox chant – reminding us perhaps that the crowds which assembled outside the Palace were carrying icons and singing hymns. (But the crowds have their own music...) And it is difficult to see what it might ‘mean’ when the opening ‘Palace Square’ music appears across the whole orchestra as the climax of the second movement. Of course, it does not have to ‘mean’ anything. Some commentators have tried bravely to provide a narrative explanation – musically, it justifies itself.

Similarly, the timpani solo near the beginning has a musical function, providing the minor and major third of the opening (harmonically ‘incomplete’) bare fifth: a modal ambiguity characteristic of the late Shostakovich. His last string quartet ends with a viola trill between the major and minor third of its final chord – and indeed this symphony ends with a major fifth across the orchestra while bells ring out the same timpani motif, its major/minor ambiguity still unresolved.

The opening of the first movement (Palace Square) sets out the symphony’s three basic motifs: a chorale based on an open fifth in the strings, a timpani solo in triplets and a trumpet fanfare. These will be developed and recombined throughout the symphony, forming its musical backbone; all other ideas are derived from revolutionary songs, or indeed are literal quotations. Their texts supply a politically impeccable subtext; whether the composer was in turn hiding a riskier subtext behind that is, again, up to each listener to decide. The first is Listen (by P. Sokal’sky to words by Ivan Golts’-Miller, from 1864), in the first entry of the flutes. Its text begins: ‘Like an act of betrayal, like the conscience of a tyrant, the autumn night is dark.’ Importantly, it employs a triplet rhythm related to the timpani solo; it is contrasted with the sharper dotted rhythm of The Prisoner (by Nikolai Ogarev), and both are developed before the opening music returns.

Ninth of January follows without a break (as will the other movements). It opens with a shadowy triplet figure in the lower strings – a free extension of the first movement’s timpani solo, in a much faster tempo. This is combined with a closely related theme, from a song by Shostakovich himself – the sixth of his Ten Poems on texts by revolutionary poets (1951). The movement builds in a series of climaxes of increasing power, before the music which opened the symphony is heard in the woodwinds. A snare drum solo begins the most clearly programmatic passage in the work: a contrapuntal section beginning with a variation of the opening timpani solo, now presented sharply in the lower strings. It builds to another – this time, brutal – climax, with the opening string music now heard fff from the entire orchestra, subsiding finally into a return of the symphony’s opening texture, with the addition of shuddering trills.

In Memoriam, essentially a funeral march, is without doubt the emotional heart of one of Shostakovich’s least intimate works. It begins with a bass line derived from the opening timpani solo. The viola melody which soon enters is from another revolutionary song, You Fell a Victim. Again it builds – rather more inexorably – to a climax. At its peak, it recalls the triplets of the second movement, once more with Shostakovich’s own song heard across the orchestra.

The Tocsin is an alarm signal; it was also the title of a 19th-century revolutionary journal. It bursts in on the slow movement’s ending with another quotation. This time, it is from a song by A. Vaknyanin to a translated Polish text: ‘Rage, you tyrants, scoff at us, threaten us fiercely with prison, with chains! We are free in our souls, though our flesh be trampled on...’ The themes of previous movements return, and the final climax is capped by the alarm-bell itself.

Carl Rosman © 2000

First performance:

30 October 1957, Moscow, Natan Rachlin conducting.

Most recent WASO performance:

17 April 1993. Vladimir Verbitsky, conductor.

Instrumentation:

piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, cor anglais, two clarinets, bass clarinet, two bassoons and contrabassoon; four horns, three trumpets, three trombones and tuba; timpani, five percussion, two harps, celeste and strings.