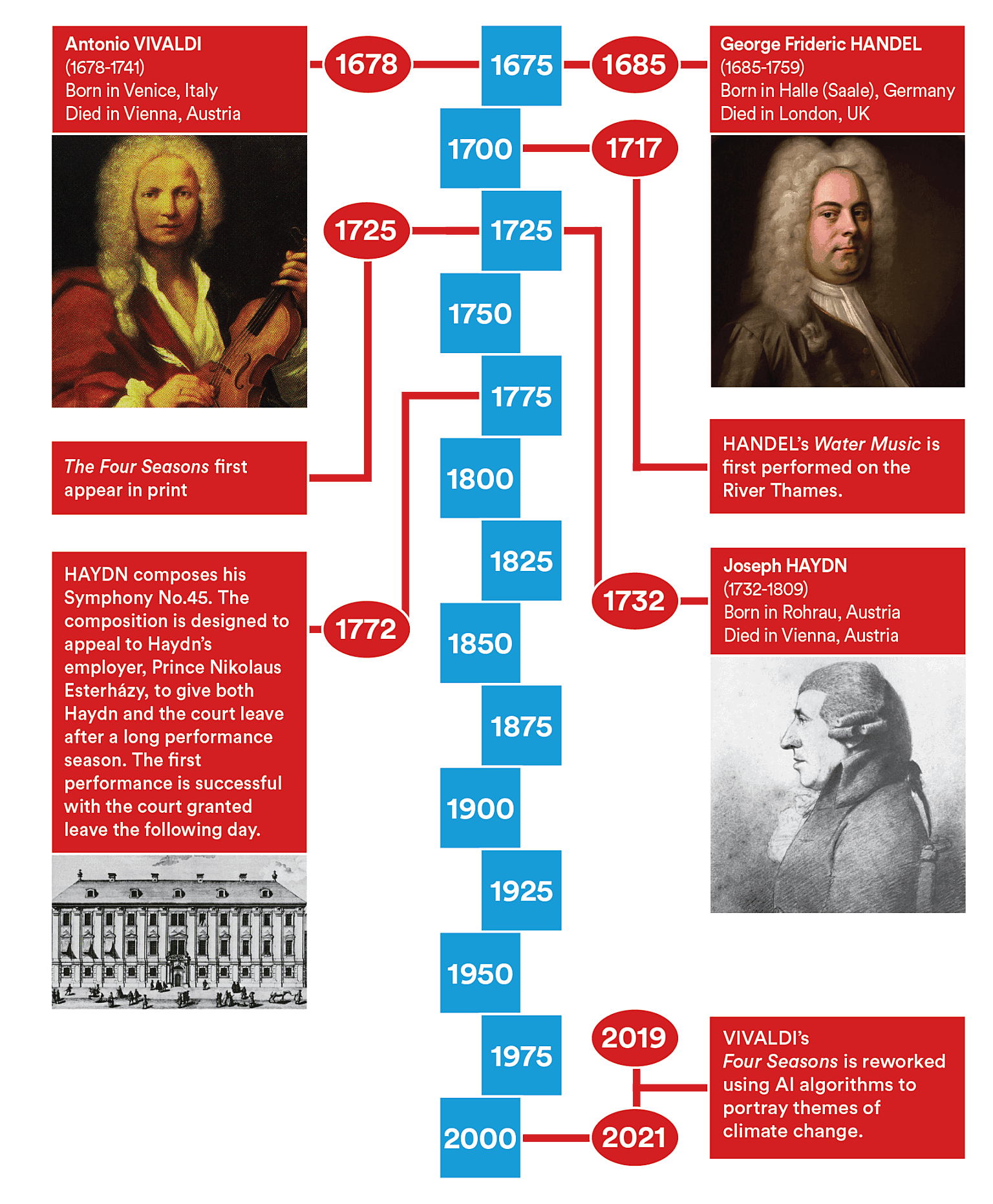

Antonio Vivaldi (1678 – 1741)

The Four SeasonsConcerto in E, RV 269,

La primavera (Spring)

Allegro

Largo

AllegroConcerto in G minor, RV 315,

L’estate (Summer)

Allegro non molto

Adagio – Presto

PrestoConcerto in F, RV 293,

L’autunno (Autumn)

Allegro – Allegro assai

Adagio molto

AllegroConcerto in F minor, RV 297,

L’inverno (Winter)

Allegro non molto

Largo

Allegro

Antonio Vivaldi died in Vienna in July 1741 and was buried in an unmarked grave. His music was rarely if ever played between then and the 1930s, when musicians in Italy began rediscovering Vivaldi’s huge and varied output of works. With the interest of music scholars like Alfred Einstein, composer Alfredo Casella and poet Ezra Pound, the revival of Vivaldi began; by the end of the 20th century Vivaldi was once again one of the most popular and frequently performed composers.

Despite his death in obscure poverty, Vivaldi had enjoyed great popularity and success during his lifetime. Born in Venice in 1678, Vivaldi began learning violin with his father, a professional musician. He began studying for the priesthood in his early teens, though this in no way would have been seen as conflicting with the expectation of a career in music. It should be noted, too, that in Vivaldi’s time one was not obliged to enter a seminary; he was effectively ‘apprenticed’ to an older priest and was eventually ordained.

Although ordained a priest, Vivaldi spent his adult life as a composer and violinist. His works included some 500 concertos as well as many operas, instrumental sonatas and a large body of sacred music. He pioneered the solo concerto, rather than the more common concerto grosso which had, at the very least, a pair of solo instruments. This was in part a vehicle for his own virtuosity; his playing was clearly prodigious – one contemporary describes how Vivaldi ‘put his fingers but a hair’s breadth from the bow, so that there was scarcely room for the bow’. He also experimented with violin technique, developing methods like position shifts, the use of mutes and pizzicato to create new sounds and effects, often with specifically illustrative intent.

Venice in Vivaldi’s time was, as H.C. Robbins Landon puts it, ‘a city past its prime’, yet it maintained a rich and elaborate cultural life. A particular feature of the city was the establishment of a number of orphanages for girls that doubled as music academies. In 1703, the year he was ordained, Vivaldi began teaching at one such orphanage, the Ospedale della Pietà. In his capacity as director of music at the Pietà, Vivaldi composed the first known concertos for cello, bassoon, mandolin and flautino (sopranino recorder). On the available evidence, the students were very fine players indeed.

The Four Seasons forms part of Il cimento dell’armonia e dell’inventione (‘The Contest of Harmony and Invention’), Opus 8, which was published in 1725 in Amsterdam. The Four Seasons is a frankly programmatic work. French composers had a tradition of music imitating nature, but Vivaldi was one of the first Italian composers to experiment in this vein. Vivaldi’s rhetoric exquisitely depicts the seasons’ progress, described also in sonnets (possibly written by him) which he affixed to the score.

The bright opening of the first concerto reflects joy at the arrival of spring, and the soloist’s entry sets off a chain reaction of trilling birdcalls over a static bass. Rippling passages suggest running water, and the menace of distant thunder can be heard before the birds sing again. In the slow movement, a goat-herd falls asleep among murmuring plants, not even disturbed by the repeated barking of his dog. In the finale Botticellian nymphs and shepherds perform a rustic dance with bagpipe drone.

Summer’s first movement embodies a sense of heat-struck lassitude with only the intrepid cuckoo and turtledove calling, as the shepherd fears the encroaching storm. This apprehension is carried over into the unquiet slow movement, before the storm arrives in all its fury in the finale.

Autumn begins with peasants celebrating the harvest with dance and song, and, as the movement progresses, Vivaldi creates a striking musical image of drunkenness. In the slow movement, the peasants sleep off their binge, before going hunting in the finale. This contrasts cantering ‘hunting’ music with the panic of the quarry, which is caught and killed.

Snow, ice, chattering teeth and a cruel wind inform the first movement of Winter, but for the slow movement we go indoors and enjoy a crackling fire as the rain beats on the windows. The finale begins with ice-skating, weaving different voices in slow-moving elegant arcs. The ice cracks, the skater shivers, and the four winds are unleashed.

Gordon Kerry © 2005/2010

First performance:

The Four Seasons first appeared in print in 1725 but we do not know when exactly they were composed or first performed.

Most recent WASO performance:

1-2 May 2015. Shaun Lee-Chen, violin. Paul Dyer director.

Instrumentation:

Strings and continuo only.