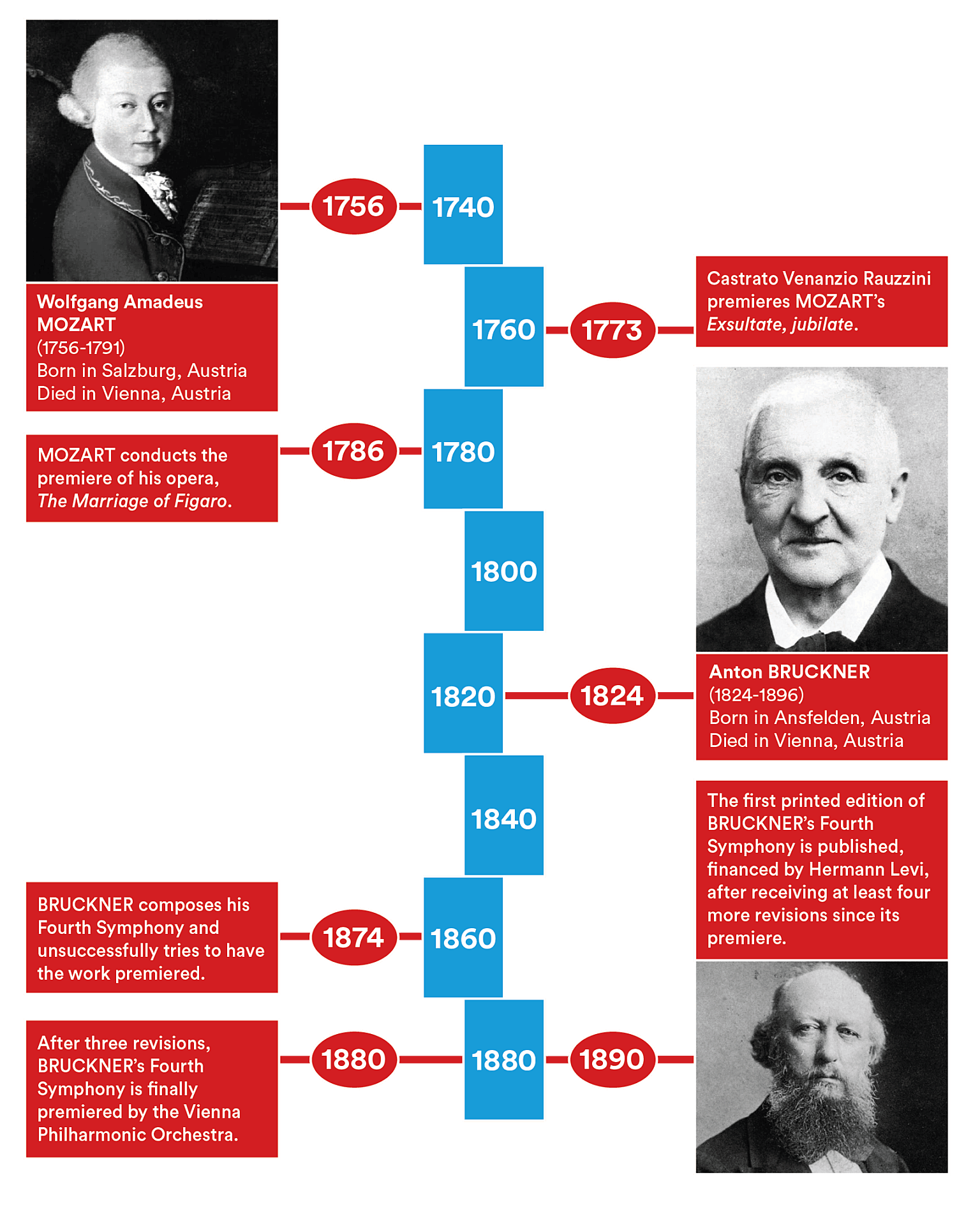

Anton Bruckner

(1824-1896)

Symphony No.4 in E flat Romantic

(1878-80 version, Nowak edition)

Bewegt, nicht zu schnell [With movement, not too fast]

Andante quasi allegretto

Scherzo (Bewegt) [With movement] – Trio

(Gemächlich) [Leisurely]

Finale (Bewegt, doch nicht zu schnell)

[With movement, but not too fast]

Bruckner’s Fourth Symphony has long been his most popular. This is a puzzle, since there is a grain of truth in the superficial but amusing observation that Bruckner composed, not nine symphonies, but the same symphony nine times! The Fourth is the only symphony to which Bruckner himself gave a title, and ‘Romantic’ is an apt word for the moods and atmospheres the music evokes. Bruckner went further: when asked to explain his symphony, he invented (after composing it) an imaginary program in which the first movement is supposed to represent a medieval city at dawn, trumpet calls signalling the opening of the city gates, knights riding out into the countryside where they are surrounded by the bird calls and magic of the forest. Bruckner’s program is best ignored – this unsophisticated man provided it to oblige well-meaning friends, and the Fourth is no more programmatic than any of his other symphonies. Bruckner once said of a friend’s program for the Seventh Symphony, ‘If he has to write poetry, why does he have to pick on my symphony?’

Bruckner reluctantly tried to explain his music because its first audiences found it so hard to understand. They were not helped by Vienna’s music critics, particularly the powerful Eduard Hanslick, champion of Brahms, and deeply prejudiced against the Wagner disciple, Bruckner. When the Vienna Philharmonic played through the first version of the symphony shortly after Bruckner completed it in late 1874, all except the first movement was pronounced ‘idiotic’. The most famous of all Bruckner stories presages the success of the revised Fourth Symphony at its first performance, at a Vienna Philharmonic concert conducted by Hans Richter in February 1881. After a rehearsal, Bruckner gratefully approached Richter and slipped a coin into his hand. ‘Take it and drink a beer to my health,’ said the delighted composer.

Bruckner’s symphonies demanded a new way of listening. He is often tagged ‘the Wagnerian symphonist’, but his debt to Wagner was very partial: he studied Tristan und Isolde from a piano score without text, and when he went to hear Die Walküre he is reported to have asked someone after the performance, ‘Tell me, why did they burn the woman at the end?’ Even the orchestral and harmonic innovations in Bruckner which sound so Wagnerian – the chromatic harmony, the rich brass scoring, the expressive use of the massed strings – are present in embryo in Bruckner’s earliest orchestral music, before he became familiar with Wagner.

The true sources of the musical craft of this church-trained teacher and organist from Upper Austria lie in that country’s musical tradition – in Beethoven and even more in Schubert. Bruckner’s symphonies are not dramatic in Wagner’s sense, nor dialectical or argumentative in Beethoven’s. His inspiration, like Schubert’s, is lyrical, and the music is built into long paragraphs, put side by side, and compared by one musician to a series of terraces. ‘Schubert,’ wrote the great English musicologist Sir Donald Tovey, ‘is always ready to help Bruckner whenever Wagner will permit.’

The spirit of Bruckner hidden behind the ‘Wagnerian’ sound is entirely different from Wagner’s. As Tovey puts a truth obvious to anyone who knows Bruckner well, he never forgets the high altar of his Catholic church, nor, one might add, the magnificent organ of the Augustinian monastery of St Florian, where he first learnt music. The simple religious devotion of the man can be heard in the developments of the second subject of the Romantic Symphony’s first movement, and in the magnificent brass chorales which recur in the last movement.

It is often called organists’ music, and certainly Bruckner’s fondness for contrapuntal devices such as inversion, augmentation and diminution is very obvious in the symphonies, and shows his deep learning in the methods of the old church composers. Bruckner was one of the great improvisers at the organ, but his symphonies, despite their vast scale, are never rambling. His orchestra often sounds like an organ, but as Tovey observes, this is because it is completely free of the mistakes of the organ-loft composer. Bruckner is master of the orchestra.

Perhaps the popularity of Bruckner’s Fourth Symphony is chiefly due to its memorable opening. The mysterious beginning of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony fascinated Bruckner, and it has been said that he couldn’t get a symphony under way without a tremolo. It is not a symphony which starts, but the beginning of music itself: major and minor horn calls sounding the interval of a fifth, gradually rousing the woodwind to join in. The string tremolos continue, after a climax, as accompaniment to the second subject, and the characteristic ‘Bruckner rhythm’ of a duplet and a triplet is heard. The recapitulation starts with the opening horn calls, now surrounded by a flowing figure in muted violins, and they also provide the material of the elaborate coda.

The slow movement is an elegiac march in C minor, the relative minor key. Whereas the slow movement of Beethoven’s Ninth, often invoked as Bruckner’s model, consists of variations on two themes, the returns of Bruckner’s broad main theme are separated by an episode that returns twice, a chantlike theme for the violas heard against pizzicato notes from the other strings. Each statement of the main theme is more richly scored and displays more movement than its predecessor, rising at last to a great climax before a solemn coda.

The last two movements were subject to the revisions and second thoughts so typical of Bruckner’s career as a symphonist. Between 1878 and 1880, years after the fiasco of the first readthrough, Bruckner wrote a completely new Scherzo, and revised the Finale extensively. The success of the first performance under Richter protected the Fourth Symphony from further major revision by the composer.

Bruckner’s description of the Scherzo as a hunt with horn calls, and the Trio as a dance melody played to the hunters during the rest, is the only useful though obvious part of his ‘program’. The scale of this sounding of the horn, however, suggests King Mark’s moonlight hunt in Tristan und Isolde, or even the Ride of the Valkyries, more than Bruckner’s bucolic ‘hunting of the hare’. The Trio, by contrast, is an Austrian peasant dance with which Haydn, Mozart and of course Schubert would have felt at home.

The Finale is the longest movement, a feature of the overall balance of the symphony again suggested by Beethoven’s Ninth. As in Beethoven, there are reminiscences here of the earlier movements. A three-note descending phrase is heard in the introduction, recalling the opening of the symphony, while the brass remember the Scherzo. This phrase is gradually revealed as the main theme, played in unison by the whole orchestra. The second thematic group is dominated by a C minor melody for violins and violas, later combined with a lively woodwind motif. Themes from all the movements occur, combined most artfully with the new thematic material, as Bruckner works his way to a restatement of the symphony’s opening theme in the home key. The brass dominates the coda, with the motto of the symphony’s first pages.

David Garrett © 2002

Commissioned by Symphony Australia

This work, published by MWV/Bärenreiter Verlag, has been supplied by Clear Music Australia Pty Ltd as exclusive hire agents for Bärenreiter in Australia.

First performance:

20 February 1881, Vienna. Hans Richter conducting.

Most recent WASO performance:

2 August 2014 (1874 version). Simone Young, conductor.

Instrumentation:

two each of flutes, oboes, clarinets and bassoons; four horns, three trumpets, three trombones and tuba; timpani and strings.