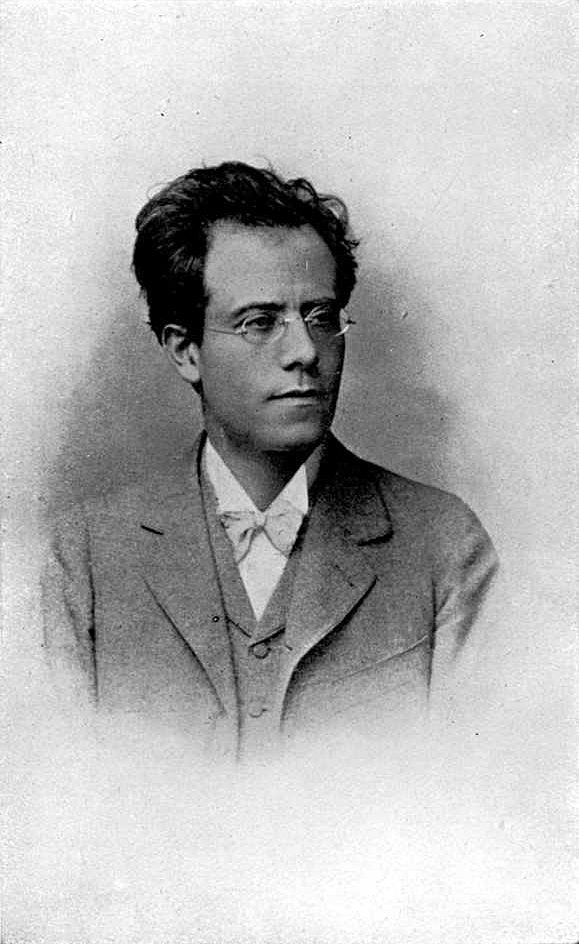

Gustav Mahler

(1860-1911)

Symphony No.1 in D Titan

Langsam, schleppend – Im Anfang sehr gemächlich (Slow, dragging – Very comfortably)

Kräftig bewegt, doch nicht zu schnell (Forcefully, yet not too fast)

Feierlich und gemessen, ohne zu schleppen (Solemn and measured, without dragging)

Stürmisch bewegt (Stormily)

Gustav Mahler once told his friend Natalie Bauer-Lechner that ‘composing is like playing with building blocks, where new buildings are created again and again using the same blocks. Indeed these blocks have been there, ready to be used, since childhood, the only time that is designed for gathering.’

Mahler’s First Symphony proved the point. Composed in 1888, he drew his idea for the first movement and middle section of the slow movement from his own Songs of a Wayfarer, the song cycle he’d composed in 1884. The scherzo contains a tune first composed by Mahler as early as 1880. The First Symphony also quotes from Wagner’s Parsifal, Liszt’s Dante Symphony, and German drinking songs.

A failed love affair played its part too. Back in 1884, Mahler and the soprano Johanna Richter parted ways after an intense affair and Mahler poured out his rejected soul in poetry, some of which found its way into the Songs of a Wayfarer and indirectly into the symphony. ‘The symphony begins where the love-affair ends,’ Mahler wrote subsequently. ‘The real life experience was the REASON for the work, not its content.’ Mahler composed the bulk of the work in just six weeks in the early spring of 1888, juggling the conducting of opera rehearsals and performances at the Leipzig City Theatre with early morning and late evening composition. In early 1888 this punishing regimen had resulted in his completion of Weber’s opera The Three Pintos. Inspired by its success, the 28-year-old Mahler launched into his new symphony with fanatical concentration. ‘It flowed out of me like a mountain river. For six weeks I had nothing but my desk in front of me.’

When the first movement was done, he played it on the piano for the Weber family, who were stunned and requested an encore. But the work would never enjoy such immediate approval again.

By contemporary standards, the completed symphony was massive. Nearly an hour long and in five movements (originally including a slow movement, Blumine), it employed a large orchestra including seven horns and four trumpets. Mahler conducted the premiere in 1889 in Budapest (where he was now Artistic Director of the Royal Hungarian Opera), heading it ‘A Symphonic Poem in Two Sections’ and including a detailed program.

The Hungarian audience was divided, with some of Mahler’s admirers hailing it as a masterpiece, but with the majority of the public being mystified, or worse, offended.

In response, Mahler locked his manuscript away for three years, only returning to it in 1893. ‘As a whole, everything has become more slender and transparent,’ he wrote to Richard Strauss about the revision, successfully performed in Hamburg in 1893. Strauss himself programmed it in Weimar, but there, wrote Mahler, ‘my symphony was received with furious opposition by some and wholehearted approval by others. The opinions clashed in an amusing way, in the streets and in the salons.’

One of the major criticisms was that the program of the symphony, adapted from Jean Paul Richter’s novel Titan, was ‘confused and unintelligible’. The closest connection that could be made with the music was simply a vague Promethean element, a similarity of fantasy and grotesque humour, and a sense of heroic, titanic struggle. Mahler himself said that he had in mind only a generalized concept of ‘a powerfully heroic individual, his life and suffering, struggles and defeat at the hands of Fate.’

Mahler took the criticism to heart and when the next performance occurred in 1896, it bore no program and was labeled simply ‘Symphony in D major’. Blumine was dropped, turning it into the four-movement work familiar today, but even then the symphony failed to capture the imagination of its audience. For years afterwards Mahler lamented the work’s ‘cold effect on the listener’. In 1906, he advised a Paris producer not to program the work. And as late as 1909, he told Bruno Walter that there had been ‘no particular response’ to a New York performance.

Right from the outset, the score gives a clear indication of the work’s intentions. Over a suspended note, the composer writes the direction ‘like a sound of nature’ and soon we hear a cuckoo’s call which will permeate the movement as a whole. As the original program stated, it is intended to depict ‘Spring without end…the awakening of nature in the early morning.’

It need hardly be stated how revolutionary this ‘natural’ approach to composition would have sounded back in 1889. Even in the post-Beethoven era, the strict rules of traditional composition remained current in the musical capitals of Europe, and aside from the storm scene in Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony and ‘Forest Murmurs’ from Wagner’s Siegfried, there were still few precedents for a composer attempting to imitate the sounds of nature, and never at the very beginning of a symphony!

With the rise of scientific discovery and the theoretical work of Emile Zola, however, a naturalistic revolution was sweeping theatre and literature. Mahler adapted the aesthetic to music, and in doing so created a new kind of symphonic form. In it, the inconsistencies, the expansive structures, and the clash between the sublime and the facile that so characterise everyday existence found a musical form, as the tight classical structures of sonata form were exploded, quite literally with instruments now going beyond the frame and playing offstage.

Each of the work’s usual four movements has its own take on this revolutionary aesthetic. In the second movement, it’s Mahler’s employment of the ländler – not the refined waltz that we have come to expect but a much cruder, earthier and more authentic kind of peasant dance. This is Schubert and Bruckner curdling in the world of fin-de-siècle decadence and anxiety.

The slow movement is perhaps even more startling and characteristic. It’s a funeral march, but set to a children’s nursery tune – Bruder Martin in German, Frère Jacques in French. Its inspiration was a woodcut entitled The Huntsman’s Funeral Procession in which animals follow a dead man’s coffin: hares, cats, frogs and crows, all making music. Mahler’s take on the children’s illustration begins on a solo double bass and is later interrupted by some crude street music. It’s the sound of everyday life, but with fantasy and grotesquerie thrown in for an intensely unsettling effect.

The critics didn’t quite know how to react. One wrote, ‘We do not know whether we should take this “funeral march” seriously or interpret it as parody. We are inclined to assume rather the latter, as the main motive…is a well-known German student song, Bruder Martin, which we ourselves have frequently sung, albeit not at funerals but while happily drinking.’

And then of course there is one of the most famous transitions in all Mahler, with the Funeral March giving way to the shocking, shrieking, almost despairing attacca into the final movement. Mahler described this transition as being ‘like a flaming accusation of the Creator’ and also ‘the cry of a deeply wounded heart’. But this apocalyptic final movement ends in triumph, with the radiant key of D major gradually taking over for a conclusion of deep beauty and emotion.

Adapted from a note by Martin Buzacott © 2003.

First performance:

20 November 1889, Budapest. Gustav Mahler, conductor.

First WASO performance:

The West Australian Symphony Orchestra first performed the four-movement version of Mahler’s First Symphony in 1966 under the direction of Thomas Meyer.

Most recent WASO performance:

20-21 November 2015. Asher Fisch, conductor.

Instrumentation:

four flutes (2nd, 3rd, 4th also piccolo), four oboes (3rd also cor anglais), four clarinets (3rd, 4th also E♭, 3rd also bass clarinet), three bassoons (3rd also contrabassoon), seven horns, four trumpets, three trombones, tuba, two timpani, cymbals, triangle, tam-tam, bass drum, harp, strings.