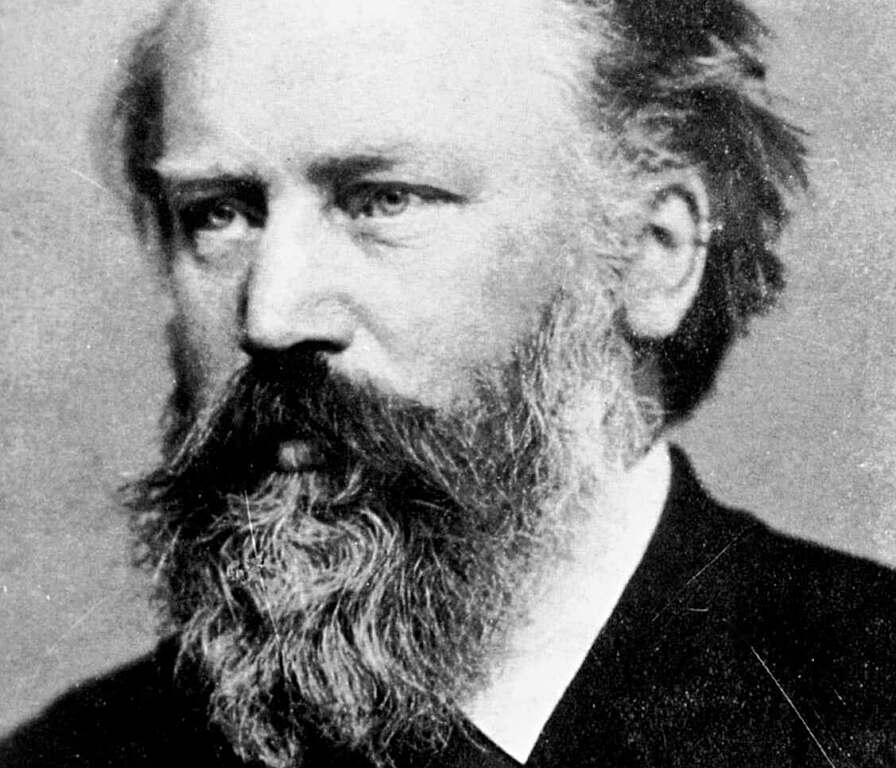

Johannes Brahms

(1833-1897)

Concerto for violin, cello and orchestra in A minor, Op.102

Allegro

Andante

Vivace non troppo

Brahms could be difficult, as several friends found to their cost. His relationships with Clara Schumann, Elisabeth von Herzogenberg and others to whom he entrusted his music for criticism were often punctuated by frosty periods, and his friendship with the great violinist Joseph Joachim, first interpreter of the Violin Concerto and

Violin Sonata in G major, was fraught with misunderstandings: in 1884, when Joachim and his wife divorced and Brahms, believing her to have been wronged, took Amalie’s side, the friendship ruptured completely.

In the early 1880s Brahms frequently collaborated with the conductor Hans von Bülow, touring extensively as soloist in both of his Piano Concertos and conducting a number of his orchestral works. But then in 1885 a misunderstanding arose between them and the two were estranged for a year. Partly as a showpiece for Robert Hausmann, the cellist for whom Brahms wrote his sonatas, but largely to heal the rift with Joachim, Brahms composed the Double Concerto in 1887; at the same time, his olive branch to Bülow was the dedication of his Violin Sonata in D minor.

Both, along with a number of other significant late works, were composed during summer vacations on Lake Thun in Switzerland, the Double Concerto dating from 1887. The rift with Joachim was most definitely healed when he and Hausmann played through the piece with the composer at Baden-Baden later that year, in the presence of perhaps the one friend with whom Brahms never completely fell out: Clara Schumann.

It is Brahms’ last orchestral work, and not surprisingly exhibits a number of features of Brahms’ (and indeed many composers’) ‘late style’. Unlike, say, the Violin Concerto, this is a work that underplays its virtuosity; in fact, after that first rehearsal the solo parts were revised, three or so times in the case of the violin part, to make them more, not less, difficult. Joachim and Brahms both had strong views on how that might be achieved, though in a letter to Clara Schumann he admitted, with needless modesty, that he needed the advice of someone ‘better acquainted with fiddles’ than he was. She in turn noted the work was one of ‘reconciliation’, but felt that it lacked ‘warmth and freshness’. In this she was hardly alone, if more polite than one friend who mocked it as a ‘senile production’, and even Joachim took some time to properly love it. More recent scholars have been marginally more generous. It is easy to criticise it for not being something else; it is fairer to see it as an experiment in a new kind of work that lacks grandiose pretentions.

The unusual combination of soloists – Brahms’ own idea – presented some problems of balance which Brahms, naturally, solved: the orchestra provides strong rhetorical statements of major thematic material, but is then deployed in textures of great delicacy when accompanying the soloists. The work’s opening, for instance, offers an arresting orchestral gesture that sets up the typically Brahmsian tension between duple and triple metres, before leaving the stage to a lengthy passage for the cello, a second orchestral flourish (containing a reminiscence of a Viotti concerto which was a favourite of Joachim’s) and then the violin joined by the cello. This alternation between strenuous orchestral textures and the ornate writing for the soloists continues throughout the movement.

The serene beauty of the Andante derives partly from Brahms’ exquisite use of the wind section, often in the simplest of harmonies, to create a cool backdrop for the restrained but still expressive themes, stated first in octaves by the two soloists, that move, via hymnal woodwind writing and antiphony for the violin and cello, to a generous, lyrical climax. The ‘late style’ character here is music that makes its effect with the simplest means, though which remains alive to the possibilities of formal intricacies like counterpoint. The finale is, naturally, an example of Brahms’ ‘gypsy-rondo’ style, which plays on sudden contrast between perky and lyrical, duple and triple metres, and solo writing which features ornate passagework and hefty double-stopped chords. By way of a coda there is an exquisite, slightly slower passage of delicate tracery before the rondo theme brings the piece to a close.

© Gordon Kerry 2014/15

First performance:

18 October 1887, Cologne. Composer conducting.

Most recent WASO performance:

22 August 2015. Asher Fisch, conductor; Pinchas Zukerman, violin and Amanda Forsyth, cello.

Instrumentation:

two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets and two bassoons; four horns and two trumpets; timpani and strings.