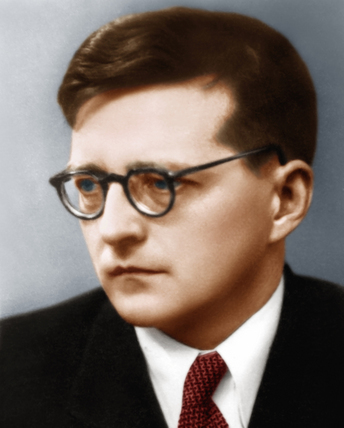

Dmitri Shostakovich

(1906-1975)

Symphony No.9 in E flat major, Op.70

Allegro

Moderato

Presto –

Largo –

Allegretto

What was Shostakovich thinking? He of all people knew that discretion can be the better part of valour. Despite its popular success, his opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk had been savaged – possibly by Stalin himself – in the pages of the Party newspaper, Pravda, and the composer knew that denunciation often preceded ‘disappearance’. At the height of the Great Terror of the late 1930s, therefore, Shostakovich prudently held back his inevitably controversial Fourth Symphony and produced the Fifth which, with its ostensibly positive outlook, returned him to precarious favour for the time being.

Shostakovich might have been daunted by the prospect of writing a Ninth Symphony. Not only was there the precedent of Beethoven’s hybrid masterpiece, but Bruckner, for instance, had gone to his eternal reward before completing his Ninth, and this in turn had led Mahler – according to his

wife, anyway – to such an excess of superstition that he refused to give Das Lied von der Erde a number in his symphonic sequence. A Ninth is an enormous challenge; for Shostakovich this was compounded by other circumstances. Two years earlier his Eighth Symphony had been criticised publicly by Prokofiev at an assembly of the Composers’ Union. More importantly, the Ninth Symphony dates from 1945 and was expected to celebrate the Red Army’s victory over Fascism – indeed, Stalin is said to have ‘suggested’ that Shostakovich use Beethoven’s Ninth as the model for a massive, optimistic choral symphony.

Shostakovich started work on such a piece in 1944, by which time the Soviet armies had begun to force the German retreat. His efforts proved fruitless, however, and he set it aside until August 1945, finishing the piece in a few short weeks. It was, however, as unlike Beethoven’s Ninth as it was possible for Shostakovich to write. Lasting little over half an hour, and without a chorister in sight, it is almost defiantly simple in its design. The first movement begins with the kind of Rossinian melody in which Shostakovich specialised, its seemingly cheerful diatonic character tweaked every so often by an unexpected change of key, or a barely perceptible change of metre. We hear both of these devices in the first few seconds of the piece: in the violins’ first theme, and after the short answer from the solo flute. The movement as a whole is characterised by this apparent levity, which is enhanced by elements like the cartoonish piccolo solo, the fondness for circus-like music, the self-parody of the movement’s final bars and comically abrupt ending.

The second movement is curiously understated, its waltz tempo thrown slightly out of registration by seemingly random 4/4 bars, its texture often ‘hollow’ with a solo line (again, frequently given out by a wind instrument) some octaves above the bass. Even moments of

fuller scoring are somehow unfulfilling, often trailing off suddenly, as does the movement itself with a deflating sequence in the winds, and a desiccated texture barely able to support the solo piccolo.

The final three movements are played without a break, beginning with a deftly energetic scherzo introduced, characteristically, by a solo wind – the clarinet. The fourth movement essentially is a strange little recitative for solo bassoon, introduced by self-consciously ceremonial trombones and punctuated by listless chords colored by the cold sound of a cymbal hit with a timpani stick. The solo bassoon’s recitative becomes by degrees the theme of the final movement, which has all the energy that the preceding section lacked. Once again the manner of the movement is apparently light-hearted, even glib, with strong resonances of comic opera in its seemingly simple melodies and shamelessly gauche scoring. Once again though, and as if it were in the middle of a rally between strings and winds, a simple V-I cadence summarily brings the game to an end.

This was not the piece that Stalin, nor anyone else, was expecting – but it is a measure of Shostakovich’s ambiguity that its tone can be interpreted as the ‘sheer joy of making self-sufficient music’ or as a bitterly ironic response to the world left behind by the second world war. Theodor Adorno believed that poetry was no longer possible after Auschwitz; Shostakovich, writing in the aftermath of the horrors in Eastern Europe and as the bombs fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, clearly felt that there was little to glorify.

Gordon Kerry

Symphony Australia © 2001

First performance:

3 November 1945, Leningrad. Yevgeny Mravinsky, conductor.

Most recent WASO performance:

14 September 1974.

Carlo Bagnoli, conductor.

Instrumentation:

piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, three percussion and strings.