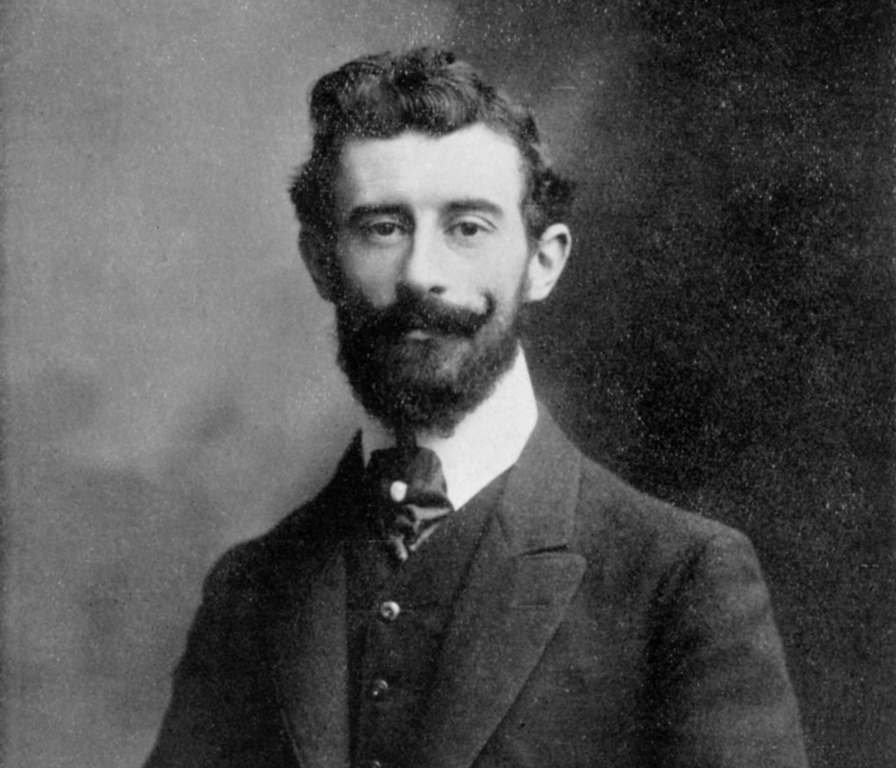

Albert Roussel

(1869-1937)

Bacchus et Ariane, Op.43 – Suite No.2

Introduction

Ariadne awakens

Dance of Bacchus alone

The Kiss

The Dionysiac spell

March past and presentation of the golden

goblet to Ariadne

Ariadne’s Dance

Dance of Ariadne and Bacchus

Bacchanale

The ballet Bacchus et Ariane, composed by Albert Roussel in 1930, had its premiere at the Opéra in Paris in 1931. The choreography was by Serge Lifar, who danced the role of Bacchus, and the designs were by Giorgio di Chirico. Roussel later made two orchestral suites for concert performance. The second suite, which corresponds exactly to the second act of the ballet, had its first performance in the Salle Pleyel, Paris, in 1934 under Pierre Monteux.

The suites from Bacchus et Ariane are Roussel’s most often performed music, belonging to the fullest artistic maturity of this individual and distinguished composer. Roussel was a late starter, beginning to compose on shipboard while training to be a naval officer. He reached the rank of Lieutenant before deciding at age 25 to become a professional musician. Roussel’s early music is marked to a certain extent by the Franckian harmony and cyclical structures favoured at the Schola Cantorum, where he studied under Vincent d’Indy, and later taught. Elements of Impressionism mark works such as Evocations (1910-11), inspired by travels in Asia, and Le festin de l’araignée (The Spider’s Feast, a ballet). The success of these led to the commission of a remarkable opera-ballet on an Indian theme, Padmâvatî, whose completion was delayed by World War I.

After the war, Roussel clarified his style still further – uncommon harmonic combinations, ingeniously irregular rhythmic patterns, a melodic language favouring wide leaps, and a preference for independent counterpoint. Roussel’s mastery of instrumental effect gives his music brilliance and clarity, but ‘like a winter sun gives more light than heat, revealing the nakedness of the surrounding country without increasing its fertility’ (Martin Cooper). Bacchus et Ariane partly escapes this generalisation: its outlines are as strongly drawn as an etching, but strong primary colours break through Roussel’s usual slight reserve into passionate expression, as befits the Dionysian subject. Along with the Third Symphony (composed for the 50th anniversary of the Boston Symphony Orchestra in 1930), Bacchus et Ariane was one of the triumphs of Roussel’s later years. Fastidious composer of a small body of work, his unique personal language had no followers, though he was the mentor of composers of whom the most famous is Frank Martin.

Ballet music suited Roussel. When he wrote that ‘the directness of the rhythm constitutes a trump card in the hand of the ballet master, [and] the clarity of the melodic line is no less valuable’, he was naming the strongest points of his own music. The classicism of Bacchus et Ariane, the marine setting, and the intoxication of the Dionysian dances were ideal for a musician of Roussel’s gifts.

The concert suites stand up very effectively without the stage action. It may help the listener to connect Ariadne first with the tender viola solo of the introduction, then with a solo violin as she dances in Dionysian frenzy. Bacchus is introduced by clarinet figures strongly reminiscent of Richard Strauss’ Till Eulenspiegel. Roussel has written music of sustained invention, and avoided merely illustrative detail. The tonal plan of the ballet and each of its acts has a strong and satisfying logic. In this and other respects, comparison with Ravel’s ballet Daphnis et Chloé of 1912 is inevitable. The subject matter is similar, but as Basil Deane writes in his study of Roussel, ‘Ravel’s form is expansive, his rhythm flexible, and his harmony caressing. Roussel condenses his material; his rhythm is taut and his chords astringent’.

The story of the ballet

The story of the ballet, by Abel Hermant, is set on the island of Naxos where Theseus has landed with Ariadne, daughter of King Minos of Crete, and the youths and maidens he has rescued from the Minotaur, with the help of Ariadne’s thread in the labyrinth. Theseus and his companions celebrate their deliverance, and he mimes his duel with the monster. A sinister veiled figure appears. Ariadne approaches him, and falls asleep under his power. He is none other than Bacchus himself: he orders Theseus and his companions to leave the island. In a dream Ariadne dances with Bacchus.

Here the second act of the ballet (and the second suite) begins. Ariadne awakens and finds herself abandoned. She climbs the rocks and sees the receding sail of Theseus’ galley. She tries to throw herself into the sea, but falls instead into the arms of Bacchus. They resume the dream dance. Their lips meet in a kiss, releasing an enchantment, and the sterile island suddenly becomes populated with fauns and bacchantes. These followers of Bacchus march past. Two of them present Ariadne with a golden cup filled with grape juice. She drinks and, intoxicated, dances with mounting frenzy, first alone, then with Bacchus. The entire company joins in a Bacchanalian revel, while the god conducts Ariadne to the highest pinnacle and crowns her with a diadem of stars ravished from the constellations.

David Garrett © 2001

First performance of the ballet:

22 May 1931, Paris.

Most recent WASO performance:

28-29 September 2001. Jean Bernard Pommier, conductor.

Instrumentation:

piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, english horn, two clarinets, bass clarinet, two bassoons, contrabassoon, four horns, four trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, triangle, tambourine, drum, cymbals, bass drum, tam tam, celesta, two harps, strings.