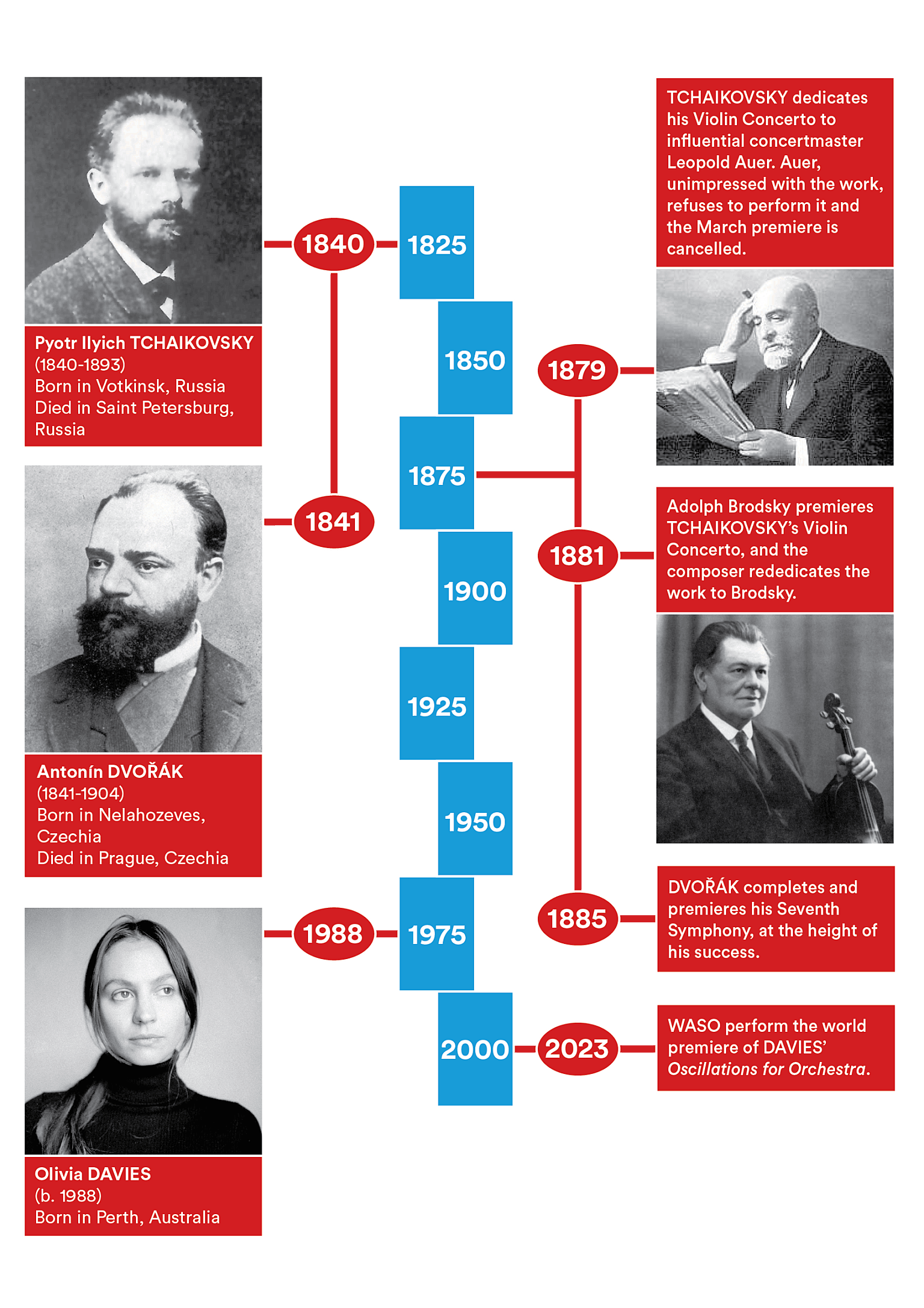

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

(1840-1893)

Violin Concerto in D, Op.35

Allegro moderato

Canzonetta (Andante) –

Finale (Allegro vivacissimo)

The first bad review of a masterpiece has a curious allure. There is something forlorn and fascinating about the French critic of the 1850s who proclaimed that Rigoletto ‘lacks melody’, or George Bernard Shaw’s declaration that Goetz was a greater symphonist than Brahms. Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto is a distinguished member of that company of musical masterpieces that survived a traumatic debut to become one of the most beloved works of its kind.

It could almost be described as a love letter. In 1878 the composer was still feeling the repercussions from his shortlived marriage and took a holiday with his brother Modest in Clarens on Lake Geneva. In March they were joined by the violinist Josef Kotek. One of Tchaikovsky’s pupils at the Moscow Conservatory, Kotek had introduced the composer’s music to his future patron, Nadezhda von Meck. At some point in their long friendship, according to Tchaikovsky biographer Alexander Poznansky, the two men became lovers. In Clarens, composer and former student spent some time playing over various unfamiliar pieces, including Lalo’s Symphonie espagnole, then a new work which Tchaikovsky admired for its piquancy and melodiousness. The combination of Lalo’s concerto and Kotek’s presence inspired in Tchaikovsky a desire to write a violin concerto himself. He immersed himself in work on the concerto and had it fully sketched in a few weeks. By the end of April he had orchestrated the whole work.

Kotek’s advice and encouragement, and his belief in Tchaikovsky’s abilities, were crucial in the work’s composition. Kotek was originally to have been the concerto’s dedicatee, but Tchaikovsky was concerned at the gossip this would cause in Moscow, and instead dedicated the work to Leopold Auer, a renowned performer and teacher, whose pupils were to include Mischa Elman and Jascha Heifetz.

Tchaikovsky’s hope that Auer’s fame would help promote the concerto was dashed when Auer claimed that the work was technically impossible and structurally weak; in short, that he would not learn it. Then Kotek decided that he didn’t want to play it either, which caused Tchaikovsky to break with him altogether. In fact three years were to pass before Jurgenson, who had since published the score, informed Tchaikovsky that Adolph Brodsky was planning to play the piece at a Vienna Philharmonic concert under Hans Richter in December 1881. There was a furious mixture of applause, boos and hissing afterwards, with Brodsky being acclaimed and the work derided. The Viennese critics, always fairly conservative, were almost universal in their condemnation of the concerto. The most influential of these was Eduard Hanslick, champion of Brahms and enemy of Wagner, who wrote a review of infamous vituperation.

For a while the concerto has proportion, is musical, and is not without genius, but soon savagery gains the upper hand…The violin is no longer played: it is yanked about, it is torn asunder, it is beaten black and blue.

Tchaikovsky was shocked at the vehemence of Hanslick’s review, but Brodsky was not dissuaded and remained the work’s most fervent champion. Auer eventually overcame his opposition to the concerto and played it to great acclaim, also introducing it to many of his pupils.

The work opens with a scene-setting introduction, after which the soloist enters with a brief flourish, then announces the main theme of the first movement. Soon the second subject appears, a melody of great tenderness. From this point the temperature of the first movement rises considerably, with the solo part becoming much more virtuosic and the orchestral writing increasingly colourful. There is a magnificently varied cadenza for the soloist.

Kotek felt Tchaikovsky’s original slow movement was too insubstantial and sentimental, and the composer agreed, replacing it with the Canzonetta. After a simple chordal introduction for the woodwinds, the soloist takes up a hushed, appropriately song-like theme. This is one of Tchaikovsky’s most purely beautiful creations. He eventually published the original version of this movement as Souvenir d’un lieu cher, Op.42.

The Finale follows on without a break, and immediately the soloist has a dazzling, short cadenza, which leads straight into the movement’s vigorous main theme, a short, folk-like dance tune. The second theme, introduced over a bagpipe-like drone on the strings, is a temporary lyrical resting-place in the movement’s wild infectiousness.

Abridged from a note by Phillip Sametz © 1996

First performance:

4 December 1881, Vienna. Hans Richter, conductor; Adolf Brodsky, soloist.

First WASO performance:

1 June 1946. Walter Susskind, conductor; Vaughan Hanly, soloist.

Most recent WASO performance:

22 June 2019. Asher Fisch, conductor; Vadim Gluzman, soloist.

Instrumentation:

two each of flutes, oboes, clarinets and bassoons; four horns, two trumpets; timpani, and strings.