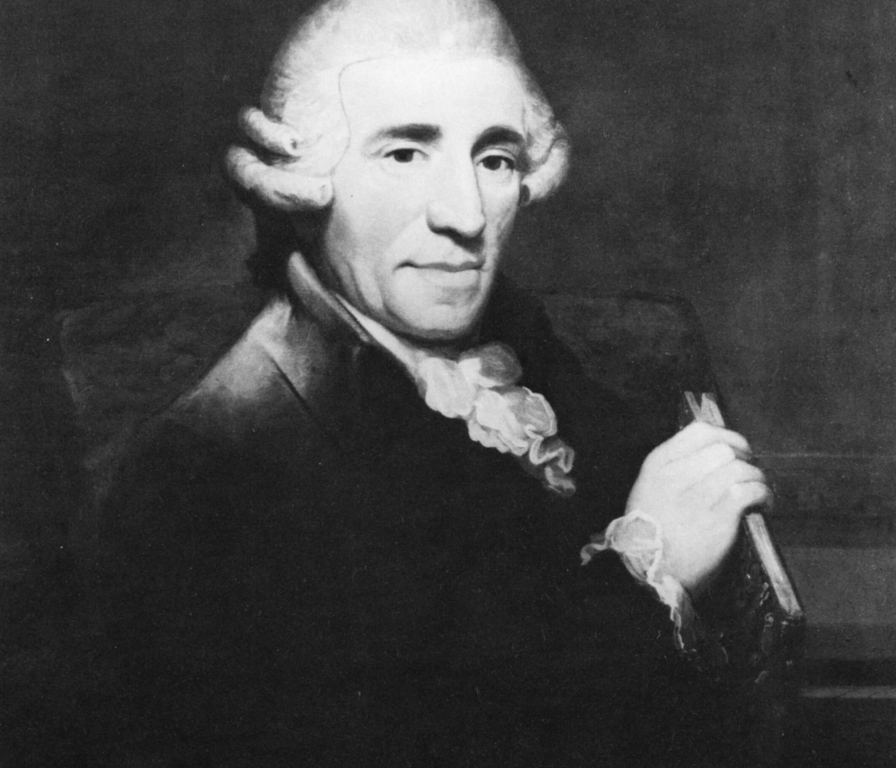

Joseph Haydn

(1732-1809)

Mass in D minor Hob.XXII:11

Missa in angustiis (Nelson Mass)

I. Kyrie. Allegro moderato

II. Gloria. Allegro

III. Credo. Allegro con spirito

IV. Sanctus. Adagio

V. Benedictus. Allegretto

VI. Agnus Dei. Adagio - Vivace

VII. Dona nobis. Allegro vivace

The

Nelson Mass is the most celebrated of Haydn’s late masses. It owes its fame partly to its historical association with Lord Nelson, but more importantly to its superb musical qualities, its unity of inspiration, and its special, challenging sound. Some authorities have claimed this is Haydn’s greatest single work.

Haydn composed his six last masses after returning in 1795 from his second visit to London. Nicolaus II, the fourth Prince Esterhazy Haydn had served, required of his

Kapellmeister only that he write a mass each year for the September name day of his Princess, Maria Hermenegild. The third of these compositions was the Missa in angustiis, a title which could be freely translated ‘Mass in dire straits’. In that summer of 1798 the threat of Napoleon to Austria and Europe seemed extreme, and Europe’s embattled state is certainly reflected in the music, especially the

Benedictus, which is invaded by fanfares for trumpets and drums. Trumpet fanfares in the mass were an old Austrian tradition, but no-one ever used itas dramatically and memorably as Haydn does here.

Haydn was composing this mass while Nelson was fighting the battle of Aboukir on the Nile; when news of Napoleon’s defeat reached Vienna, people wept for joy. Haydn later studied the battle with keen interest, and he too thought it meant the end of Napoleon’s domination, but he could not have known of the battle until after the mass was finished. In September 1800, two years after the mass was first peformed, Nelson visited Eisenstadt and gave Haydn the watch he had worn at Aboukir. The composer gave him his quill pen in return. Nelson almost certainly heard then a performance of the ‘Nelson’ Mass, and this may be the real origin of the name by which the piece became known in Austria and Germany.

Haydn’s

Nelson Mass declares its challenging individuality straight away, with a unison descending D minor

arpeggio, punctuated by menacing trumpets in their lowest register, and gaining an ‘acidic’ character from the held chords on the organ. This is Haydn’s only mass in a minor key, and for a moment it may seem that he has returned to the tense world of his ‘Storm and Stress’ symphonies of 20 or more years before.

The difference is in the greater breadth of phrase and of harmonic movement. Haydn has found a settled sureness of style, symphonic, but able to be turned to any purpose. The

Nelson Mass, and its immediate predecessor,

The Creation, are very different, but equally sure in their unforced originality.

The trumpets, though first sounded low, are high ‘clarino’ trumpets. By the time voices come in, we have heard the full instrumental complement of this mass: three trumpets, kettledrums, strings and organ. Soon we will discover that the organ has a solo,

concertante part in many places. This unusual instrumentation was a necessity: in 1797 the Prince had dismissed the wind ensemble which played at the castle of Eisenstadt and reinforced the court orchestra. When this mass was first published, the solo organ part had been eliminated and replaced by oboes and bassoons, along with many other alterations. Haydn himself never revised or rescored this mass. He knew his instrumentation was exceptional, and was not worried by the reaction of contemporaries who found the music ‘noisy’. The organ part, which he played himself, was designed to show off the organ in Eisenstadt’s Stadtpfarrkirche, the church where the mass was first performed on 23 September 1798. Modern editions of the

Nelson Mass, such as the one for tonight’s performance, return to Haydn’s original intentions.

The

Kyrie immediately reveals the dramatic and symphonic character of this mass, as the soprano soloist leads from the opening themes of this urgent prayer for mercy to an exciting sonata-form development of these figures. She then reappears with thrilling effect soaring on elaborate runs over the reprise of the opening by chorus and orchestra. The soprano also leads off the

Gloria with the music which returns to knit it together. A cheerfully affirmative movement in D major, this music moves away from the oppressed character of the

Kyrie. ‘Laudamus te’ is set to unison off-beat phrases, marked by sforzandi. ‘Qui tollis’ is a bass solo beginning with a phrase broadly spanning a downwards octave, answered by the strings gracefully turning upwards. At ‘Miserere nobis’ the organ plays its first conspicuous solo. These ideas are built into a rising supplication for mercy, a tension released by the return of the

Gloria theme, set to the words of the ‘Quoniam’. The

coda to the whole movement is an exciting fugue on the words ‘In gloria Dei Patris, Amen.’

The

Credo begins with a relentless twopart canon at the fifth; ‘Et incarnatus’ brings a touching contrast in a graceful Rococo solo, a hymn to the Virgin which links this mass with Mozart’s Litanies. Haydn’s account of the Passion is in tense chromatic unison phrases, joined by fanfares; the music becomes halting and quiet. The outburst at ‘Et resurrexit’ is punctuated by dramatically placed pauses in a headlong rush. Throughout the monotone chanting of the articles of faith, tension is built by repetition and brilliant string figuration, finally blooming into an ecstatic vision by the soprano soloist of the life of the world to come.

A concise

Sanctus emerges from and returns to silence – an island of contemplation. Hairpin dynamics in the choir’s singing are reminiscent of ‘Chaos’ from

The Creation, and punctuated by a staccato thud from trumpets and timpani. The

Osanna shows a masterly handling of tension and relaxation. Perhaps the

Benedictus is the most remarkable movement of all: an orchestral procession, ever more detailed and elaborate, given touches of unease by rests and soft trumpet notes. Then, after some wonderfully rich alternations of solo quartet and choir, comes what the great Haydn authority H.C. Robbins Landon calls ‘the boldest and most powerful music in the whole of Haydn’: a bar’s rest, then a tremendous warlike hammering of the note D by trumpets, drums, and chorus, as though Europe were pleading for a saviour from the ravages of war. The conclusion of the mass in the

Agnus Dei and ‘Dona nobis pacem’ is typical of the whole, combining brilliance, rhetoric (in the solo soprano’s recitative-like passage), learning (the fugue) and sombre dramatic force, the rhythms at once exuberant and uneasy.

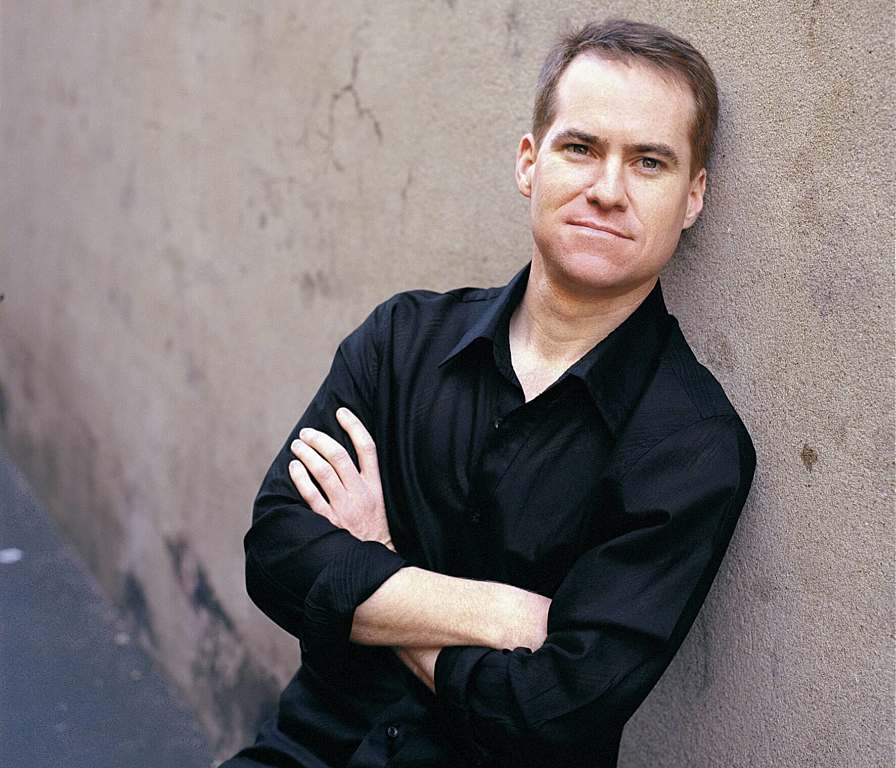

© David Garrett 2002

Year of Composition:

1798.

First WASO Performance:

1964; Frank Callaway, conductor. With the West Australian Choral Society.

Instrumentation:

one flute, two oboes, two clarinets, bassoon, two horns, three trumpets, timpani, organ and strings.