Radiant Rachmaninov - Morning

MORNING SYMPHONY SERIES

Thursday 23 November 2023, 11.00am

Perth Concert Hall

West Australian Symphony Orchestra respectfully acknowledges the Traditional Custodians and Elders of Country throughout Western Australia, and the Whadjuk Noongar people on whose lands we work and share music.

How to use your Digital Program

Radiant Rachmaninov - Morning

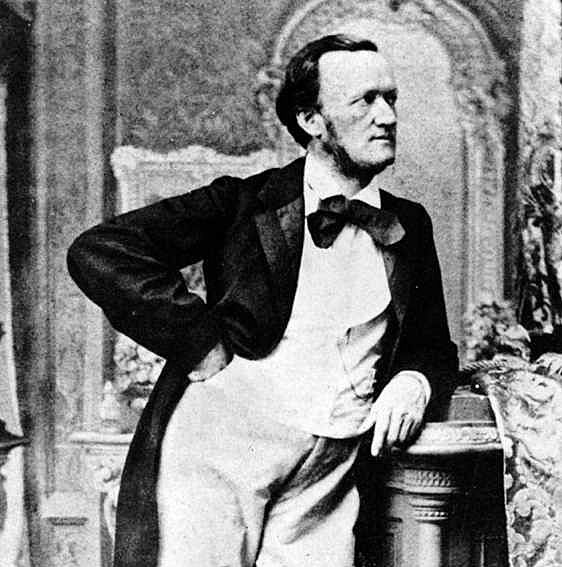

Richard WAGNER Lohengrin, Act I: Prelude (9 mins)

Sergei RACHMANINOV Symphonic Dances (35 mins)

Non Allegro

Andante con moto (Tempo di valse)

Lento assai – Allegro vivace

Asher Fisch conductor

Simon Trpčeski piano

Asher Fisch appears courtesy of Wesfarmers Arts.

Wesfarmers Arts Pre-concert Talk

Find out more about the music in the concert with this week’s speaker, Cecilia Sun. The Pre-concert Talk will take place at 9.40am in the Main Auditorium.

Listen to WASO

This performance is recorded for broadcast on ABC Classic. For further details visit abc.net.au/classic

WASO On Stage

About the Artist

About the Music

About the Music

Sergei Rachmaninov

(1873-1943)

Symphonic Dances, Op.45

Non AllegroAndante con moto (Tempo di valse)

Lento assai – Allegro vivace

After Rachmaninov left Russia in 1917, the seizure of his Russian income by the Soviet government meant he had to earn a living as a performing musician, and so he set about establishing his career as a concert pianist. Although famous for interpreting his own music, he had never been called upon to perform music by other composers in public, and now, at the age of 44, he began building up a soloist’s repertoire. This left little time for composition, and he wrote no original work for another nine years. Then the urge to compose began to reassert itself. A fitful procession of ‘Indian summer’ pieces emerged between 1926 and 1940, many of which are now regarded as among his finest compositions. But at the time most of these works met with indifference from audiences and hostility from critics. His success as a pianist far outstripped that of his music.

Among the first fruits of his period in the West were the Fourth Piano Concerto (1926) and the Variations on a theme of Corelli (1931). Neither was successful. The public and critical acclaim for his Rhapsody on a theme of Paganini (1934) gave him the confidence to write his Third Symphony (1936), to which, in the composer’s words, ‘audiences and critics responded sourly’. This indifference to his music sapped his confidence once again.

The orchestral style Rachmaninov cultivated in his later years was marked by great clarity of texture, a freer and more independent approach to brass and woodwind writing, and a tendency to express ideas more concisely than in his earlier large-scale pieces. Harmonically and rhythmically, his music of the 1930s bears the influence of Prokofiev and Stravinsky, but very much on Rachmaninov’s own terms. His melodies still move, on the whole, in stepwise fashion, in the manner of Russian Orthodox chant, and although he clothes his melodies in lighter textures, he is not ashamed to write tunes that could be called ‘vintage Rachmaninov’.

The result was too ‘modern’ and lean-sounding for audiences who wanted him to keep rewriting the Second Piano Concerto, and too conservative for critics, whose twin gods were Stravinsky and Schoenberg. Collectively, the Symphonic Dances represent perhaps the richest results of Rachmaninov’s new approach to the orchestra. They were also his last original composition.

The idea of a score for a programmatic ballet had been at the back of Rachmaninov’s mind since 1915, and when Michel Fokine successfully choreographed the Paganini Rhapsody in 1939 the opportunity presented itself again. He wrote the Dances the following year, giving the three movements the titles Midday, Twilight and Midnight respectively. At this point the work was called Fantastic Dances. Fokine was enthusiastic about the music but non-committal about its balletic possibilities. His death a short time later cooled Rachmaninov’s interest in the ballet idea. He deleted his descriptive titles, substituted the word ‘Symphonic’ for ‘Fantastic’, and dedicated the triptych to his favourite orchestra, the Philadelphia, and its chief conductor Eugene Ormandy.

It is a work full of enigmas which Rachmaninov, surely one of the most secretive of composers, does nothing to clarify. In the coda of the first movement, for example, there is a transformation from minor to major of a prominent theme from his first symphony, which at that time Rachmaninov thought he had destroyed (it was reconstructed from orchestral parts after his death). The premiere of that work in 1897 had been such a fiasco that Rachmaninov could not compose at all for another three years. The reference in this new piece had a meaning that was entirely private.

There is also the curious paradox that the word ‘dance’, with its suggestion of life-enhancing, joyous activity, is here put at the service of a work that is essentially concerned – for all its vigour and sinew – with endings, with a chromaticism that darkens the colour of every musical step. The sense of foreboding and finality is particularly strong in the second movement, with its evocations of a spectral ballroom, and in the bell-tolling and chant-intoning that pervade the finale. Here the extensive use of the Dies irae (Day of Wrath) theme from the Mass for the Dead (a regular source for Rachmaninov) and the curious inscription ‘Alliluya’, written in the score above the last motif in the work to be derived from Orthodox chant, suggest the most final of endings mingled with a sense of thanksgiving.

Abridged from a note by Phillip Sametz © 1999

First performance:

3 January 1941; The Philadelphia Orchestra conducted by

Eugene Ormandy.

First WASO performance:

5-6 May 1989; Albert Rosen, conductor.

Most recent WASO performance:

12-13 October 2018; Ludovic Morlot, conductor.

Instrumentation:

two flutes and piccolo, two oboes and cor anglais, two clarinets and bass clarinet, two bassoons and contrabassoon, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, alto saxophone, timpani, percussion, harp, piano and strings.

Glossary

Russian Orthodox chant – a type of plainchant, the traditional music of the Russian Orthodox Church. It is unaccompanied singing of a unison melody with no sense of any regular rhythm or pattern of strong and weak beats.

Programmatic – describes music which is inspired by and purports to express a non-musical idea, such as a story or a particular scene.

Coda – a concluding section added to the basic structure of a piece or movement to emphasise the sense of finality.

Chromatic/chromaticism – use of notes that are not part of the key.

Motif – a short, distinctive melodic or rhythmic figure, often part of or derived from a theme.