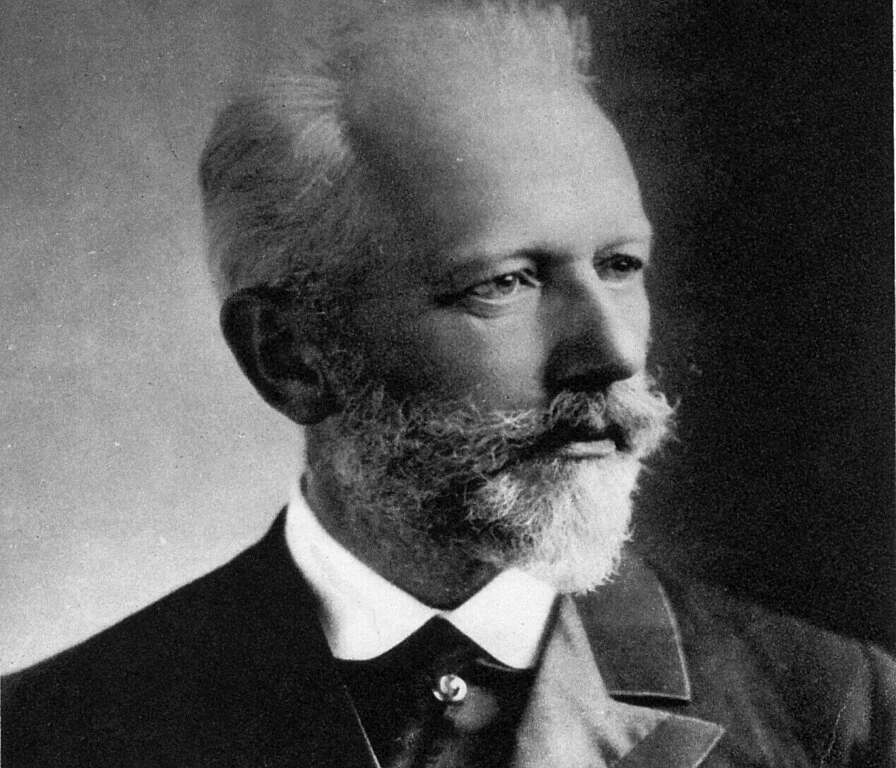

Antonín Dvořák

(1841-1904)

Symphony No.9 in E minor, Op.95 From the New World

Adagio – Allegro molto

Largo

Scherzo (Molto vivace)

Allegro con fuoco

Dvořák composed his ninth, and last, symphony in New York between January and May 1893. As his secretary, Josef Kovařík, was about to deliver the score to the conductor of the first performance, Anton Seidl, Dvořák suddenly wrote on the title page, ‘From the New World’. That expression had been used in a welcome speech following his arrival in New York the previous September. Kovařík said the inscription was just ‘the Master’s little joke’; but the ‘joke’ has, ever since, begged the question: how American is the New World Symphony?

Dvořák could have written his ‘New World’ inscription, as in the welcome speech, in English. By writing it in Czech he was seen to be addressing the work, like a picture postcard, to his compatriots back in Europe. At the same time he challenged listeners to identify depictions of America or elements of American music. Either way, the composer was seen to be meeting the desire of his employer, music patron Jeannette Thurber, for music which might be identified as American.

Mrs Thurber had persuaded Dvořák to become director of her National Conservatory of Music in New York. Besides teaching students from a wide spectrum of society, he found he was expected to show Americans how to create a national music. So, controversially and perhaps naively, in a country which had not forgotten the Civil War, the egalitarian Dvořák told Americans they would find their future music in their roots, whether native or immigrant, and in particular the songs of the African Americans.

From his familiarity with gypsies in Europe, Dvořák had famously composed a set of Gypsy Melodies (including ‘Songs my mother taught me’), and was thus receptive when introduced soon after his arrival to the songs of the African Americans – the sorrow songs and spiritual songs of the plantation. As a devout man of humble rural origins, he responded to the pathos and religious fervour of the poor.

He told the New York Herald that the two middle movements of his new symphony were inspired by Longfellow’s epic poem The Song of Hiawatha, a work he had long ago read in Czech and which Mrs Thurber was now suggesting for an opera. The famous slow movement, he said, was inspired by Hiawatha’s wooing of Minnehaha and the Scherzo by dancing at the wedding feast. Without using Native American melodies, he claimed to have given the Scherzo ‘the local colour of Indian music’ – an effect probably limited to repetitive rhythms and primitive harmonies.

As music, the New World Symphony is entirely characteristic of its composer (the ‘simple Czech musician’ he liked to style himself) and owes nothing to any specific ‘borrowings’ from the indigenous or African American musics Dvořák encountered in the New World. The ersatz-spiritual Goin’ home was actually arranged from Dvořák’s Largo movement by one of his students, not the other way around.

Strong non-musical impressions of America doubtless crowded the composer’s mind as he worked on the symphony. The surging flow and changing moods of the outer movements perhaps reflect the frenetic bustle of New York. The vast, desolate prairies Dvořák found ‘sad unto despair’, and this may be felt to underpin the deep yearning of the Largo (together with the composer’s own homesickness for his native Bohemia). As if to emphasise his personal longing for home, Dvořák uses a Czech dance as the central trio section of the third movement.

Musical ideas recur in the New World Symphony to link the symphonic structure. The two main themes of the first movement are recalled in festive mood in the Largo, at the brassy climax of the famous melody first stated by the cor anglais. They figure again in the coda of the Scherzo, the first theme (somewhat disguised) also making three appearances earlier in the movement. The main themes of both middle movements recur in the finale, and the main themes of all three preceding movements are reviewed in the final coda.

There, a brief dialogue between the themes of the first and last movements is cut short by a conventional cadence, spiced by unexpected wind colouring in the last chord of all.

Abridged from an annotation © Anthony Cane

First performance:

16 December 1893, New York. Anton Seidl conducting the New York Philharmonic.

First WASO performance:

28 October 1939. Malcolm Sargent, conductor.

Most recent WASO performance:

22-23 April 2022. Eduardo Strausser, conductor.

Instrumentation:

two flutes (one doubling piccolo), two oboes, cor anglais, two clarinets and two bassoons; four horns, two trumpets, three trombones and tuba; timpani, percussion and strings.