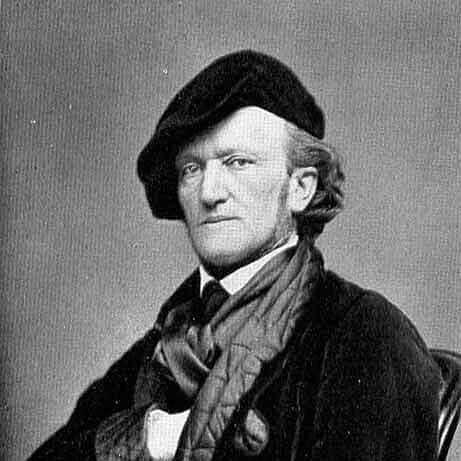

Richard Wagner

(1813-1883)

The Ring of the Nibelung (Excerpts)

1. Das Rheingold: Entry of the Gods into Valhalla

2. Siegfried: Forest Murmurs

3. Götterdämmerung: Siegfried’s Rhine Journey

4. Götterdämmerung: Siegfried’s funeral music

5. Die Walküre: Ride of the Valkyries

Last year, the West Australian Symphony Orchestra under Asher Fisch presented Act I of Wagner’s opera Die Walküre. That concert began with excerpts from operas by the Italian, Verdi, the other giant of 19th century opera, also born 1813.

This concert begins with Italian music too, the overture to Rossini’s opera The Thieving Magpie, premiered in Milan in 1817. As a kapellmeister in the 1830s, Wagner actually conducted Rossini operas, but he wrote scathingly of Rossini’s work in his theoretical text, Oper und Drama (1851). He felt that Rossinian opera promoted shallow vocal display to entertain a frivolous public.

Wagner sought something deeper: a type of opera which he called Music Drama in which the music would amplify the dramatic import of a tale designed to awaken an audience’s deepest feelings.

With works such as The Flying Dutchman, Tannhäuser and Lohengrin behind him Wagner turned to an idea he had long thought about, an opera on the German mythic hero, Siegfried. This idea turned into the Ring cycle, comprising Das Rheingold, Die Walküre, Siegfried and Götterdämmerung.

Though the entire Ring was eventually premiered as a complete cycle at Wagner’s specially built indoor amphitheatre in Bayreuth in 1876, Wagner’s research had begun in the 1840s when he conceived the idea for an opera on the subject of Siegfried’s murder at the hands of the Gibichung clan. At first, he thought he would base his opera on the 12th-century Burgundian epic, the Nibelungenlied (basically an account of the hunting-down of Siegfried’s killers). But in the end Wagner’s opera swelled in the other direction, telling of events that led up to Siegfried’s death. For this, Wagner reached into Nordic mythology to come up with a story of how Wotan the god-king created a situation where humans had to be conceived to extricate the corrupted gods from destructive behaviour he had indulged in when building a temple to his own vanity, Valhalla. In the process of creating ‘prequels’, Wagner changed the significance of Siegfried’s death into a means by which Brünnhilde, his wife, restored balance to the world.

Wagner’s Ring can be conceived as broad allegory. An environmental reading might interpret its opening (the unfurling of an E flat chord) as symbolising ‘un-corrupted’ nature. The Ring is a long way from entertainment.

Specific reforms espoused by Wagner in texts such as Oper und Drama included alliterative texts that would better impinge on the listener’s consciousness; musical modulations that followed the beats of the text; motifs identified with characters, themes or concepts whose transformation would plot dramatic progress and at the same time integrate the music; and an increased commentating role for a very large orchestra.

In general terms, Wagner’s Ring tells how a source of world-power – the gold that had lain forever on the bed of the Rhine – was stolen by the dwarf-king Alberich when he was denied love. Alberich focused much of that power in a ring which Wotan stole when looking for payment for the god-citadel. But Alberich cursed the ring so that whoever wore it was doomed. So began a quest to retrieve the ring for its power with the curse undoing everybody who possessed it until Brünnhilde allowed herself to die so that the ring could be returned to the Rhine. Was Wagner trying to say something to the German volk about the source and course of world history? The art-forms of his time – contemporary forms of opera - were inadequate to his purposes.

No wonder he came up with the Gesamtkunstwerk, bringing to the project everything he had learnt about music and theatre to that time, plus lessons from Greek tragedy and Shakespeare. No wonder he revolutionised theatre architecture, using money from King Ludwig II of Bavaria to construct a theatre for The Ring where everybody in the audience had a sightline and could focus on the stage because the orchestra was sunk beneath it.

Tonight’s extracts form teasers for the 15 hours that is the complete Ring. Played continuously they might form a kind of five-movement Ring Symphony. Individually, they provide insight into Wagner’s illustrative powers.

The ‘Entry of the Gods into Valhalla’ is a bold opening. In Das Rheingold, the giants Fasolt and Fafner have finished building Valhalla and taken Freia the goddess of youth as payment. Wotan must get her back but in doing so swaps Freia for gold and the ring (made from that gold) stolen from the bed of the Rhine. Just listening to it, the ‘Entry of the Gods’ sounds like pure victory. Story-wise, it’s ironic: the ring is cursed; Wotan has set in motion a train of destruction.

He must try to regain godly power, but needs a species not compromised by his own criminality to achieve this, so he fathers humans. Two generations down, enter Siegfried, the child of an incestuous union between Siegmund and Sieglinde. But Siegfried has been brought up by a dwarf, Mime. And in the forest he contemplates his origins before meeting a woodbird who will give him the clue to the rest of his adventures. ‘Forest Murmurs’ is a reminder, after the bombastic ‘Entry of the Gods’, that Wagner could create music of great tenderness.

After killing Fafner who had changed himself into a dragon to hoard the Rhinegold and ring, Siegfried tastes dragon blood and develops the capacity to understand birdsong. The woodbird leads Siegfried to the valkyrie Brünnhilde, asleep on a fire-ringed rock, having been turned mortal by her father, Wotan. After a night of love (in passionate music often described as “Dawn”), Siegfried gives Brünnhilde the ring most recently possessed by Fafner, and sets forth down the Rhine. A vivid scherzo portrays Siegfried’s journey, complete with billowing wave-like themes and brightening touches of glockenspiel and triangle. Siegfried arrives at the home of the Gibichungs who trick him into retrieving the ring from Brünnhilde and then murder him so they can get hold of it for themselves. Siegfried’s ‘Sword motif’ blazing out amid the darkness of the funeral march is among Ring motifs passing in review here.

To end Götterdämmerung, Wagner engineers events so that Brünnhilde, once again possessor of the ring, rides into Siegfried’s funeral pyre, from which the Rhinemaidens will retrieve what had once, in pure form, lain on the bed of the Rhine. Asher Fisch ends this digest with ‘Ride of the Valkyries’. This allegro works narratively as well as symphonically, since valkyries in German mythology took fallen heroes back to Valhalla riding horses through the air. Siegfried ends this concert dead, but transported. And we get a sense of how richly Wagner enhanced music in the quest to make it serve the drama.

Gordon K. Williams, © 2017/2024

First performance:

The Ring of the Nibelung (whole cycle), August 1876, Bayreuth Festspielhaus

Most recent WASO performance:

6 September 2017. Asher Fisch, conductor.

Instrumentation:

piccollo, three flutes, three oboes, cor anglais, three clarinets, bass clarinet and three bassoons; four horns, four wagner tubas, three trumpets, bass trumpet, four trombones and tuba; two timpani, three percussion and two harps; strings.