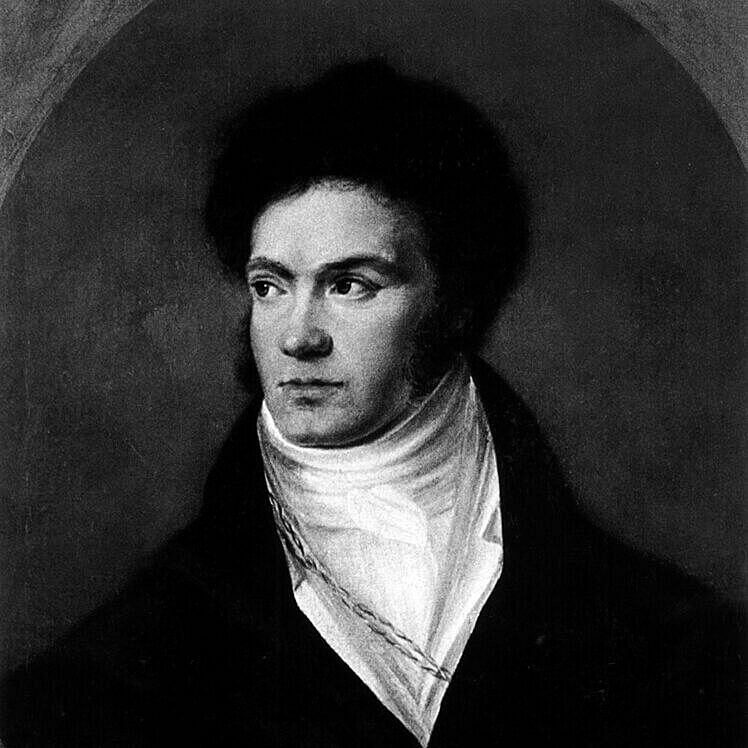

Sergei Rachmaninov

(1873-1943)

Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Op.43On leaving Russia for good in 1917, Rachmaninov descended into a composerly silence. While he busied himself with his self-appointed task of acquiring a concert pianist’s repertoire, so that he could earn a steady income, he ceased composing altogether.

After settling in the USA, he gave 40 concerts in four months during his first season there. But he gradually reduced his concert commitments until, in 1925, he had nine months free of performances. During this period, he composed his first post-Russian pieces,

Three Russian Songs for Chorus and Orchestra, which were well received, and the Piano Concerto No.4, which was greeted with widespread indifference. Rachmaninov was always sensitive about his own music, and his eagerness to bring a new

concerto into his repertoire – for his first three were by now very popular works – had been seriously rebuffed by the Fourth Concerto’s failure after its 1927 debut. He did not produce another work for four years.

When the

Variations on a Theme of Corelli for solo piano appeared in 1931, they not only signalled a more astringent approach to harmonic language and musical texture, but indicated that a large-scale

variation structure might serve Rachmaninov’s musical needs better than the more traditional concerto structure in which success had so recently eluded him.

So, the

Corelli Variations, still not particularly popular, might be thought of as the moodier, introspective dress rehearsal for the work that was to follow, the

Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini. The Corelli ‘theme’ Rachmaninov chose was actually not by Corelli at all, but was the

Baroque popular tune

La Folia, which forms the basis of a movement in Corelli’s Violin

Sonata Op.5 No.12. It was to another celebrated work for violin that Rachmaninov turned for the

Rhapsody: the 24th

Caprice of Paganini that had already been mined with distinguished results by Liszt and Brahms, not to mention Paganini himself. How confident Rachmaninov must have felt about himself – a man so often pessimistic about his musical caprice achievements – to be exploring the theme yet further, in a big work for piano and orchestra.

The

Rhapsody attained an instant popularity that has never waned. Rachmaninov finally had a new ‘concerto’ to play, and was asked to do so frequently. The work has wit, charm, shapeliness, a clear sense of colour, strong rhythmic impetus and a dashing, suitably fiendish solo part that translates Paganini’s legendary virtuosity into a completely different musical context.

In the

Rhapsody, Rachmaninov seems to grasp the big picture and distil a sense of unity, from variation to variation, that he does not achieve in the more extended forms of the Fourth Concerto. Yet the Rhapsody’s theme and 24 variations actually behave like a four-movement work. Variations 1 to 11 form a quick first movement with cadenza; Variations 12 to 15 supply the equivalent of a scherzo/ minuet; Variations 16 to 18, the slow movement; and the final six variations, the dashing finale.

We actually hear the first variation – a skeletal march that evokes Paganini’s bony frame – before the theme itself. The ensuing variations are increasingly animated and decorative until Variation 7 gives us a first stately glimpse, on the piano, of the

Dies irae plainchant, with the strings muttering the Paganini theme against it. This old funeral chant features prominently in Rachmaninov’s output. Sometimes, as in his final work, the

Symphonic Dances, he uses it without irony, but its appearances in the

Rhapsody are essentially sardonic. It appears again in Variation 10.

In the celebrated 18th Variation, Rachmaninov uses his sleight of hand to turn Paganini’s theme upside down and create a luxuriant, much admired (and much imitated) melody of his own. Rachmaninov is reported to have said of it: ‘This one is for my agent.’ The six final variations evoke Paganini’s legendary left-hand

pizzicato playing (Variation 19) and the demonic aspects of the Paganini legend, with more references to the

Dies irae and an increasing emphasis on pianistic and orchestral virtuosity in the last two variations. Just as a final violent outburst of the

Dies irae seems to be leading us to a furious crash-bang

coda, we are left instead with a nudge and a wink, as Rachmaninov’s final masterpiece for piano and orchestra bids us a sly farewell.

Abridged from a note by Phillip Sametz © 2000

First performance:

7 November 1934; the Philadelphia Orchestra. Rachmaninov, soloist; Leopold Stokowski, conductor.

First WASO performance:

16 January 1957. Donald Thornton, soloist; James Robertson, conductor.

Most recent WASO performance:

5-6 April 2019. Behzod Abduraimov, soloist; Jaime Martín, conductor.