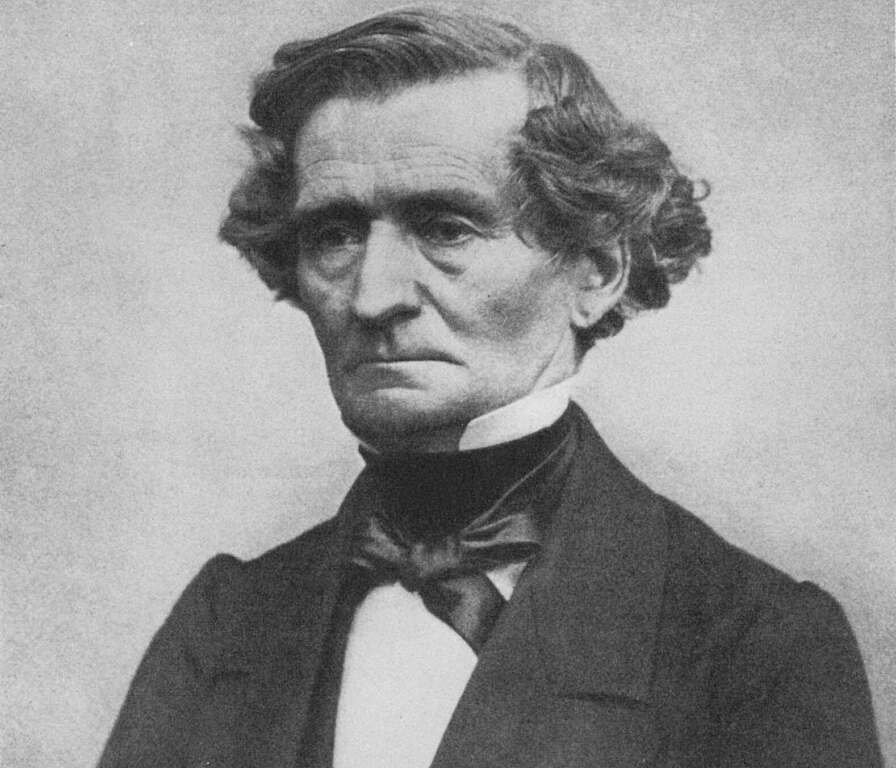

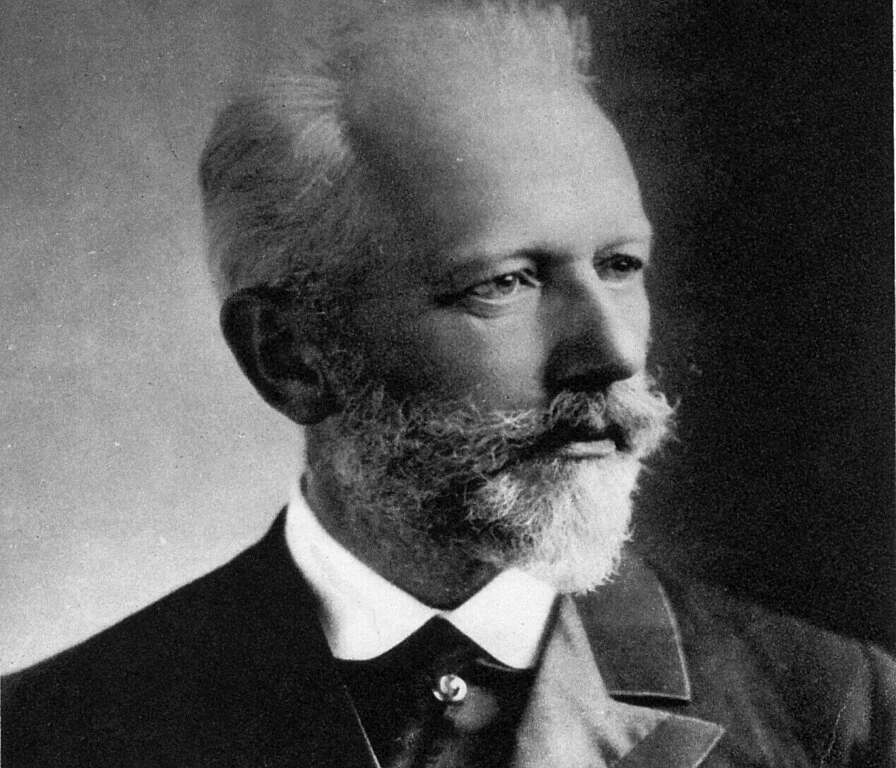

Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky

(1840-1893)

Symphony No.1 in G minor, Op.13 Winter Daydreams

Dreams of a winter journey (Allegro tranquillo)

Land of desolation, land of mists (Adagio cantabile ma non tanto)

Scherzo (Allegro scherzando giocoso)

Andante lugubre – Allegro maestoso

Tchaikovsky’s First Symphony is the product of a nervous young man in his mid-20s just appointed to a responsible teaching position in a strange city, and trying to juggle his wish to compose with his new-found professional responsibilities. It is a remarkably assured work to have been composed under such circumstances, and to many listeners unfamiliar with it, may display more of the composer’s mature stylistic fingerprints than they might expect.

Tchaikovsky had just joined the staff of the Moscow Conservatoire in 1866 when its Director, Nikolay Rubinstein, urged him to write a symphony. Tchaikovsky, who had completed his first orchestral score only two years before, began sketches immediately, and was soon working so hard on it – writing well into the night and teaching during the day – that his health began to suffer, and he made fitful progress.

By the following summer he had worked his sketches up into full orchestral score. He chose this moment to show his former teachers Anton Rubinstein (Nikolay’s brother) and Nikolay Zaremba, who were quick to find fault. Tchaikovsky’s consternation at this criticism was allayed by Nikolay’s continuing enthusiasm, and it was this Moscow Rubinstein who conducted the first complete performance in February 1868.

It was a big success for Tchaikovsky, and became one of the first Russian symphonies to find public favour; but the composer continued to make alterations, revising it in 1874 and 1883. Despite these changes, Tchaikovsky told a friend: ‘I have a soft spot for it, for it is a sin of my sweet youth.’

With young composers it is often fun to play pick the influences. Tchaikovsky scholar John Warrack has discussed the Symphony’s particular debt to Mendelssohn. Following Mendelssohn’s Scottish and Italian symphonies, Tchaikovsky seems to have wanted to create his own Romantic musical landscape, but one arising out of the emotions stirred in him by his own country. The idea must have lost its appeal, for the final two movements lack the subtitles of the Symphony’s first half. The attempt at a lightness of texture in many key passages and the surprising independence of the woodwind writing suggests Mendelssohn’s immediate influence on the work’s musical language. Yet many of the ideas seem to prefigure passages we know well from Tchaikovsky’s later music.

The first movement opens with a flowing woodwind melody that has the light, questioning quality and gentle interjections that suggest a Mendelssohnian response to landscape. The passionate development of the main ideas, and healthy doses of bombast that follow, suggest the Tchaikovsky to come, as does a balletic passage for horns and woodwinds. The brass fanfares that dominate much of the development section prefigure the tense opening of the Fourth Symphony.

The slow movement resembles one of the great ballet adagios in both atmosphere and texture. Muted divisi violins play the beautiful first subject, which is followed by a long, songful oboe melody of the kind that Tchaikovsky used to complain came to him in so finished a state that he had difficulty developing them in a symphonic context. His phenomenal gifts as an orchestrator, even in this early work, are an exquisite disguise for such structural concerns.

The Scherzo is perhaps the most overtly Mendelssohnian movement. At the opening, the lightness of the scoring is offset by a pervasive chromaticism. The Trio begins as a waltz in all but name, then develops considerable tension. The Scherzo’s reprise is followed by an unusual passage in which the timpani taps out the rhythm of the main Scherzo tune under the strings’ reminiscence of the Trio’s waltz theme. A coda that begins quietly goes on to end with two abrupt final chords.

Although some of the Symphony’s ideas sound like Russian folksong, the Finale’s opening Andante lugubre, taken from a folksong called ‘The Gardens Bloomed’, is the first folk-music to be employed in the work. The pace soon quickens and the mood becomes more festive for the main body of the movement. In the middle of the festivities there is a sudden return to the darker mood of the opening, much like the return to the motto theme at the equivalent moments in the finales of the Fourth and Fifth symphonies. However, a spirit of brightness and grandeur gradually emerges and the Symphony ends in a mood of brash jubilation.

Abridged from an annotation © Phillip Sametz

First Performance: Nikolay Rubinstein conducted the Scherzo of Tchaikovsky’s First Symphony in Moscow in December 1866, followed by a performance of the Adagio and the Scherzo in Saint Petersburg the following February. He conducted the first complete performance of the work in February 1868.

First WASO Performance: 3-4 May 1968. Ladislav Slovák, conductor.

Most Recent WASO Performance: 2-3 October 2015. Alexander Lazarev, conductor.

Instrumentation: piccolo, two each of flutes, oboes, clarinets and bassoons; our horns, two trumpet, three trombones, tuba; timpani, percussion and strings.