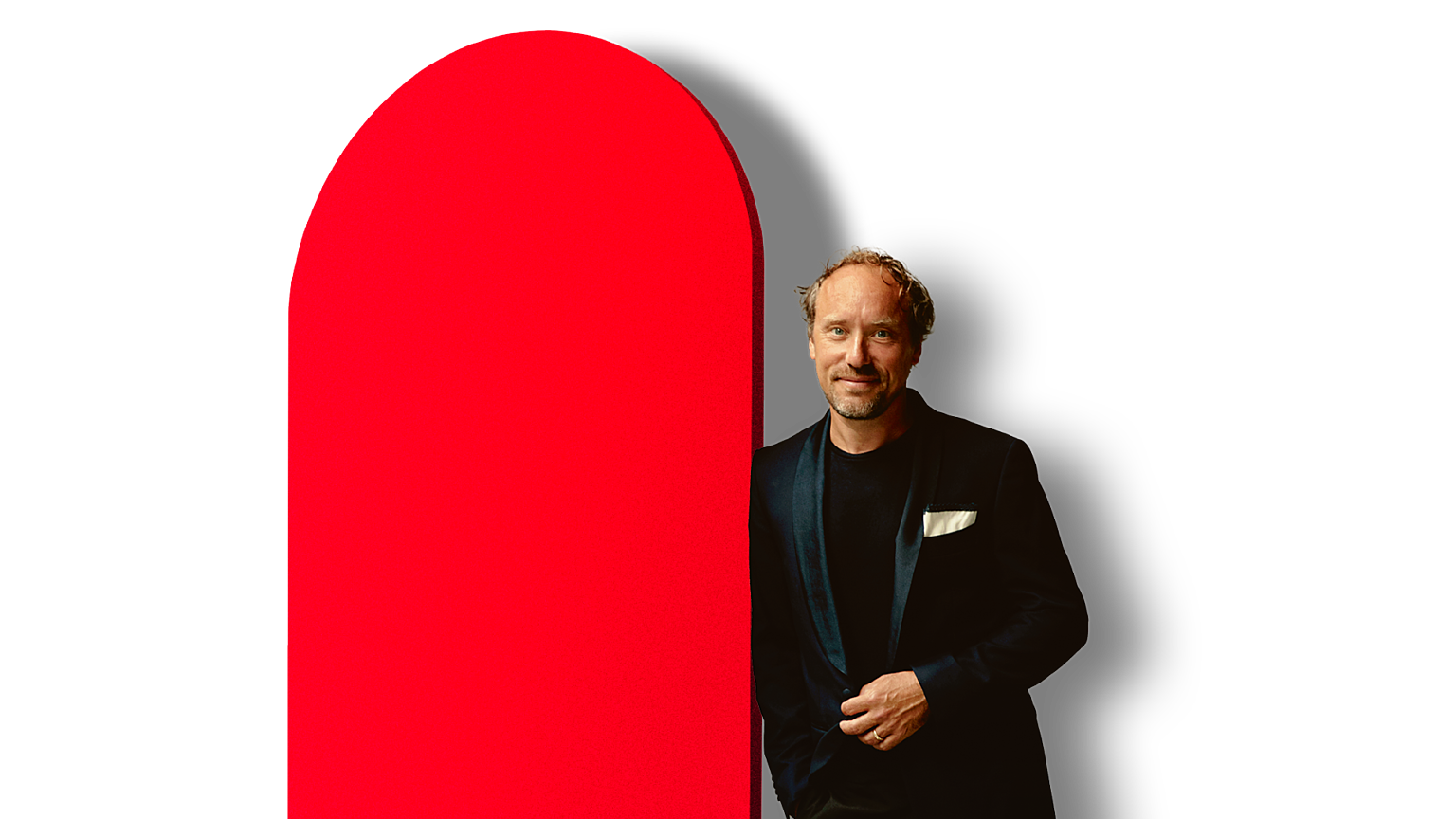

Andrew Schultz

(b. 1960)

Symphony No.4, Op.119

1. Expansive (Still, calm, distant and freely, then Faster: powerful and dramatic)

2. Circle Game (Fast – with wild andjoyous energy)

3. Chorale (Slow and elegiac, then Jubilant)

4. Gothic Burlesque (Fast, crisp, playful, then Ironic, forceful, grotesque)

Andrew Schultz’s Symphony No.4 is a 35 minute work in four movements and was commissioned for the West AustralianSymphony Orchestra by Geoff Stearn. The world premiere performances are given by the West Australian Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Otto Tausk at Winthrop Hall, Perth on 20 and 21 June 2025. The work was composed at the composer’s home in Sydney’s beachside Bronte over 2024, and completed on the last few days of that year.

Composer’s Note

Near and far. Foreground and background. Moving towards or away.

The music in my new Symphony is laid out in space and time with each listener’s ears the centre of the universe. Each movement begins with bells – metal wind chimes in the first movement, wrist bells in the second, suspended shells in the third, and zils (or finger cymbals) in the fourth. But the listener may hardly notice these bells, as they are mostly in the background and distant. They are, nonetheless, a starting point. Just as for me – a tinnitus sufferer – there are always high-pitched bell-like sounds in my head – filtered out by my brain, mostly, but occasionally there unsummoned when I’m tired or hot, and also there when I decide to listen to them to see what they are up to!

The first movement is marked Expansive, and is by turns dramatic and reflective, and is the longest of the four movements. Some years ago, I was standing by the side of a beautiful lake near the Arctic circle – a serene calm moment in early spring – sunny but cold. On the opposite bank of the lake there were big cliffs covered entirely in ice. All at once the huge ice sheets shifted then collapsed into the water and more kept coming until the whole cliff-side was free of ice. The sound arrived slowly, well after the awesome visual effect. Then, a massivewave of displaced water spread across the lake from the ice towards me. I was high up and safe but the sudden chilling contrast from calm stillness to majestic powerful motion is something I often think about and is what I have tried to capture, especially in the work’s opening few minutes and in the gentle off-stage echoes of the French horn.

The short second movement is a Circle Game marked Fast – with wild and joyous energy, and took its origins in research for a short work to celebrate East Timor and its independence struggle. The piece is based on an ancient Fatuluku children’s circle-game chant from Lautein, East Timor, as documented in Ros Dunlop’s book, Sounds of the Soul – Lian Husi Klamar, 2013. There is apparently no fully accurate translation for the text, which is in a largely lost language. My own amateur linguistic research with an old Fatuluku dictionary from Portugal suggests that it celebrates the rhythms of corn husking. But the chant is apparently still used by children in a fast-paced circle game with graphic hand and face actions, as well as virtuosic patter text.

The Chorale of the third movement is slow and elegiac. It is mostly simple music in which the expressive rise and fall of the musical swells are interrupted by reverent moments of silence or semi-silence. The resonant swells are like waves but also like the measured and steady breaths of meditation.

The fourth movement, Gothic Burlesque, is fast and plays, as the name implies, with ideas of the gothic, the macabre and the grotesque. It sits as a kind of commentary on the other movements, as well as on the grand guignol that other composers from Mozart through Berlioz and Verdi have made memorable.

By way of background, this is the first of my symphonies not to have an explicit subtitle:

Symphony No.1 (1998) was subtitled, ‘In Star Time’ and was premiered by the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra in 1998. It is a three-movement choral-orchestral work with various texts especially from Ovid’s Metamorphosis. The work takes its influence partly from Berio’s reinvention of the symphony in his epochal Sinfonia from 1967.

Symphony No.2 (2008) was subtitled, ‘Ghosts of Reason’ and is an orchestral work in one movement whose title alludes to both a psychological self-portrait and to Goya’s The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters in which he shows the mind of the artist symbolically besieged by frightening bats and owls. The work was commissioned by the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra.

Symphony No.3 (2012-13) carries the subtitle of ‘Century’. It is a three-movement work commissioned by the ACT government for the Centenary of Canberra and the Canberra Symphony Orchestra. In its three movements, it draws on ideas of reflective personal expression and dramatic public creation as embodied by Griffin’s bold designs for the new capital city. The personal and the public, the abstract and the literal, are intertwined throughout.

So, whilst various subtitles occurred to me with this new work, none in the end seemed to me to capture the range of emotional complexity of the musical argument that it embodies – it is a work that in its four movements certainly embraces subtle references and even outright quotations from other composers but is also completely based in the personal and original inner dialog that a purely abstract work allows a composer to create. To me, that ambivalence of possibility in the symphony holds a unique and exciting position in musical genres – Janus-like, looking forward and backward at once.

What Marx said about history seems also to apply to music and, in my case, to the process of writing a symphony: “Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce” (Karl Marx – 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, 1852). What Marx describes is exactly both the puzzling conundrum and exciting challenge that confronts a symphony composer in territory that in some ways is jejune and well-trodden but in many other ways offers endless imaginative possibilities. To borrow from Marx again – admittedly with him now sounding like a psycho-musicologist: people “make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under circumstances of their own choosing, but under circumstances that already exist, given and transmitted from the past. The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living.”

© Andrew Schultz, 2025

Instrumentation: piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, cor anglais, two clarinets, bass clarinet, two bassoons and contrabassoon; four horns, three trumpets, three trombones and tuba; timpani, two percussion, harp and strings.