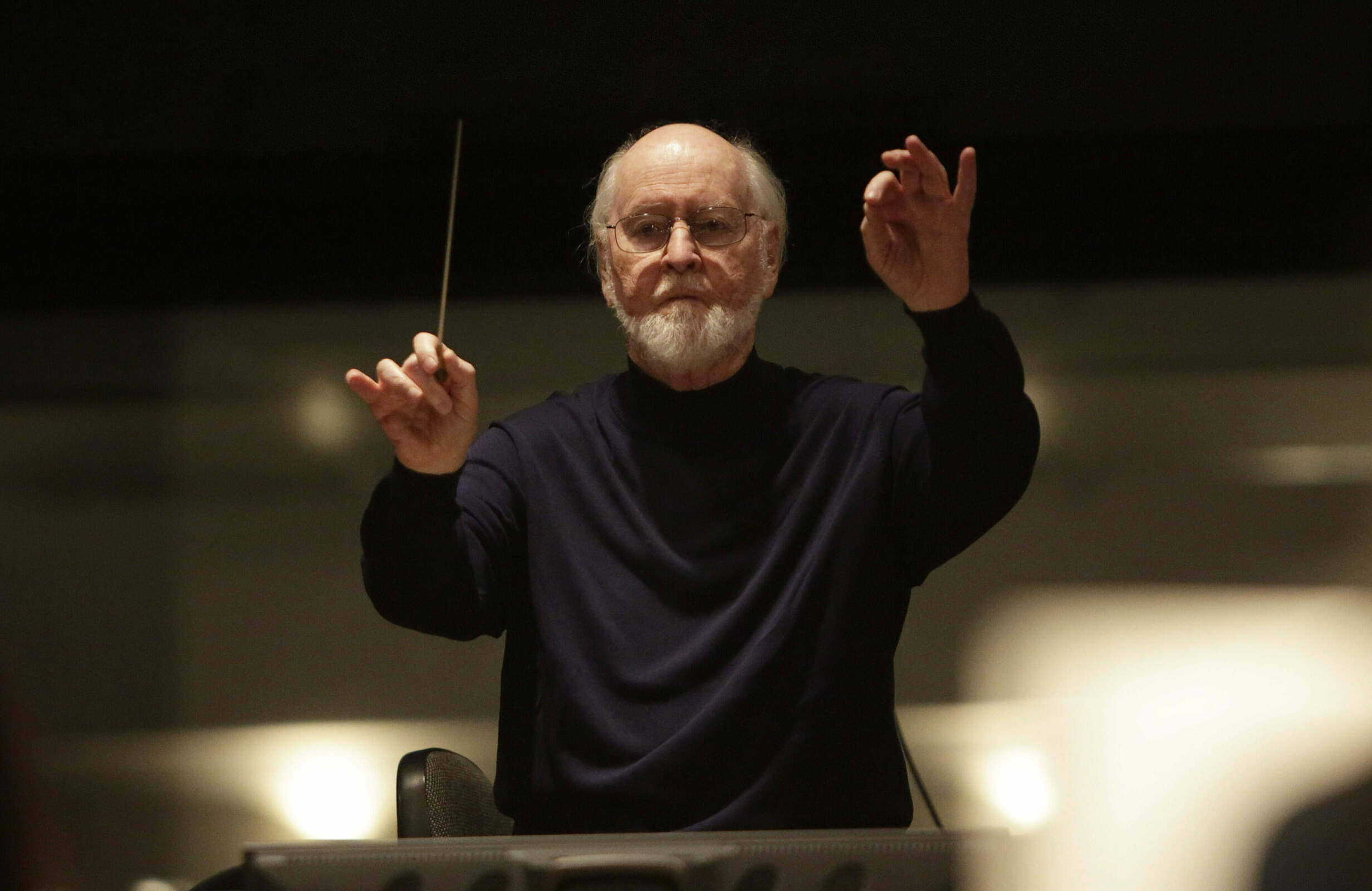

There is no person who has shaped the way we hear the movies more than John Williams. That means that when we talk about his music, his impact, and his influence, what might for others seem like hyperbole or exaggeration are just plain and simple facts.

Did you know, for example, that Williams is the second-most nominated person at the Academy Awards in any category, with well more than 50 Oscar nominations to his name? He ranks behind only Walt Disney himself in terms of sheer numbers and sustained achievement. His career has witnessed lifetimes of change at the movies.

When John Williams attended his first Academy Awards ceremony as a nominee, The Graduate was up for Best Picture, while the awards for Best Cinematography – one for black and white pictures and one for those in more expensive colour – had been merged into a single category for the first time. Seven decades later, and the movies have seen trends come and go, as well as the epochal events of digital technology and a pandemic – but still, there was John Williams in 2024, breaking his own record as the oldest nominee in any category.

Such a claim seems almost absurd, but there is also a good argument to be made that John Williams may well be the most widely heard composer in history. Though Mozart or Beethoven have a few centuries' head start, what great concert hall composer can compete with the power of the 20th century’s great mass artform, the cinema? John Williams has certainly been its chief musical envoy. Between 1970 and 1990, the yearly box office was topped by a film with music by Williams every second year, an absolute golden run that included Jaws, Star Wars, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Superman, Raiders of the Lost Ark, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial and Home Alone.

Even when adjusted for inflation, a full fifth of the top 100 films of all time at the North American box office have the John Williams touch. All this is simply to say that before you even journey to a concert hall like today, before you put on a CD of his music, before you ever opened Spotify to search for a soundtrack, you and millions like you around the world have already heard a John Williams composition. His music is in the very blood of our popular culture.

It may surprise you to learn, then, that the young John Williams did not have his sights set on the world of Mozart and Beethoven so much as Nat King Cole and Art Tatum. Williams was born to a jazz-loving family – his father was a drummer who played with Raymond Scott – and for a while it looked like Williams might take the jazz world on, first as a member of the US Air Force Band in the 1950s, and then as the pianist-leader of the Johnny Williams big band.

However, after studying piano at Julliard with Rosina Lhévinne, “it became clear that I could write better than I could play,” said Williams, and he moved to Los Angeles to become an orchestrator and session musician for the film studios. He gained an apprenticeship in film scoring in these years spent working for the likes of Henry Mancini and Elmer Bernstein, and his piano playing can be heard on Peter Gunn, To Kill a Mockingbird, and the 1960 film adaptation of West Side Story. He was composing, too, particularly for the television studios where his work for Gilligan’s Island and Lost in Space proved invaluable experience.

Williams quickly began to write for the movies, and it would prove to be one of the most fruitful artistic relationships in the history of the medium. Though Williams’ early work is full of eclectic and interesting credits – the jazz of The Long Goodbye (1973) and his klezmer-filled folk of his adaptation of Fiddler on the Roof (1971, his first Oscar) – he quickly found a niche as the musical voice of a prototypical style of blockbuster in the 1970s, films like The Poseidon Adventure (1972), The Towering Inferno (1974), and Earthquake (1974).

A young hotshot director called Steven Spielberg took note, and asked Williams if he might write music for his films. He did – for 29 films. Their second collaboration, Jaws (1975), remains one of the few movies on the planet with a theme tune hummable by almost anyone, anywhere. The very sound of a shark has become entwined with John Williams’ foreboding two-note motif, much in the same way that serial killers or showers have taken on Bernard Herrmann’s shrieking strings from Psycho (1960). Less popularly remembered, though, is the way that Williams also revived the Hollywood Golden Age sound with his music for Jaws: in among the tension and the drama there are little adventure-filled bursts of Korngold’s Captain Blood (1935) and The Adventures of Robin Hood

(1938). “I’m a very lucky man,” said Williams. “If it weren’t for the movies, no one would be able to write this kind of music anymore.”

Then came Star Wars

(1977), perhaps the most perfect match for John Williams’ nostalgic musical ability across his entire career. In the hands of director George Lucas, Star Wars was a deliberate throwback to the B-movie worlds of Buck Rogers

and Flash Gordon. John Williams gave it music to match, and then some. It was Williams, too, who persuaded Lucas to abandon the idea of classical music, a la Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), for a wholly original soundtrack: “I did not want to hear a piece of Dvořák here, a piece of Tchaikovsky there, and a piece of Holst in another place.”

The melodies that Williams wrote for Star Wars (and its many sequels and prequels) endure even today as among his most beloved. From themes for the force, to Darth Vader, Yoda, and Princess Leia, Williams revived the technique of leitmotif at the movies, a musical melody associated with characters, places, or ideas. In time, he became its master, too.

“These genuine, simple tunes are the hardest things to uncover, for any composer,” Williams told The New Yorker. Yet Williams has been better at this task than almost anyone else who has tried. For many, it seems impossible to imagine a world without the Star Wars main theme, or without that jaunty little tune for Indiana Jones.

“Without John Williams, bikes don't really fly,” said Spielberg as Williams was inducted in the American Film Institute Hall of Fame in 2016. “Dinosaurs do not walk the earth.”

More than any award or achievement, what Williams has done for the movies across seven decades is perhaps his most insurmountable achievement of all. He has given them belief.

© Dan Golding 2024