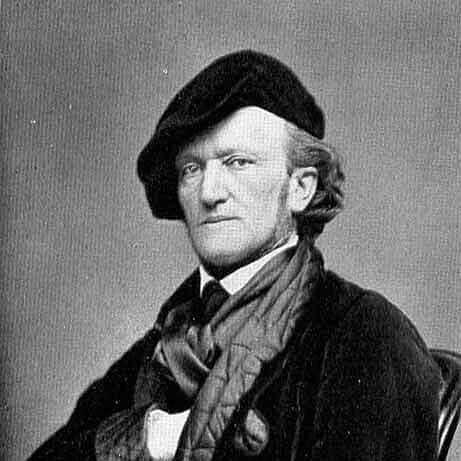

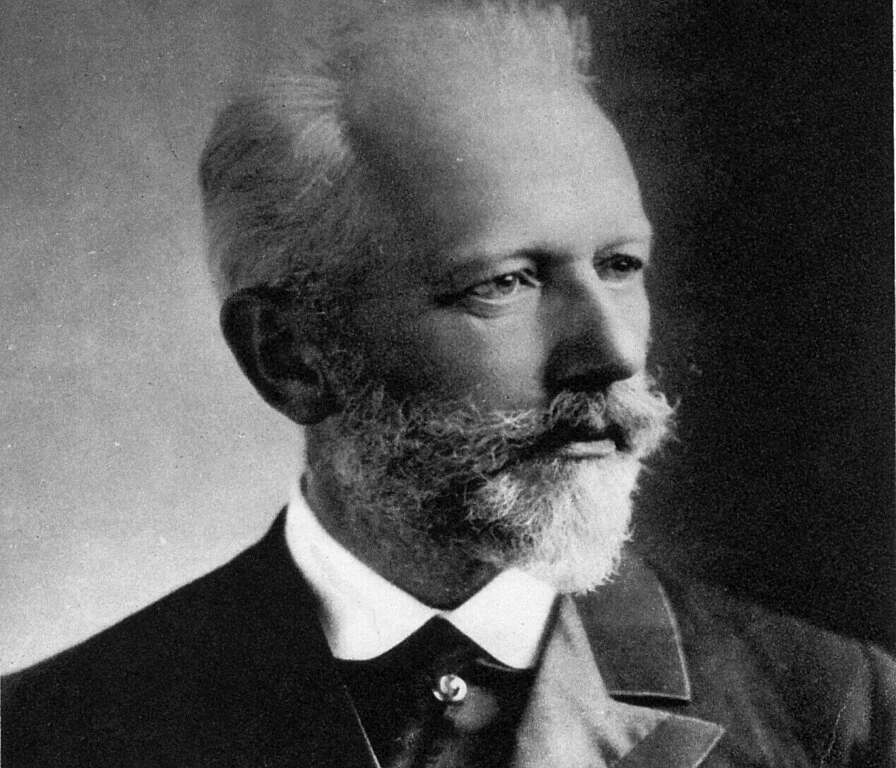

Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky

(1840–1893)

Variations on a Rococo Theme, Op.33

[Fitzenhagen version]

Introduction (Moderato quasi andante)

Theme (Moderato semplice)

Variation I (Tempo della thema)

Variation II (Tempo della thema)

Variation III (Andante sostenuto)

Variation IV (Andante grazioso)

Variation V (Allegro moderato)

Variation VI (Andante)

Variation VII and Coda (Allegro vivo)

A nostalgia for the world of the 18th century, thought of as refined, elegant and gently civilised, is never far from the surface in the highly Romantic art of Tchaikovsky. It shows in his choice of works by Pushkin – who shared and fed this nostalgia – for the books of his two best operas, Eugene Onegin and The Queen of Spades, where Tchaikovsky’s music sometimes resorts to out-and-out 18th-century pastiche. Mozart was the composer who symbolised the best of the former century for Tchaikovsky, and he revered him above all other musicians. ‘No one,’ he said, ‘has so made me weep and tremble with rapture at nearness to what we call the ideal.’ Whatever the term ‘rococo’ may mean, to Tchaikovsky it meant Mozart. This set of variations is his finest tribute to his idol’s art, far preferable to his orchestration and overlaying of Mozart pieces with a rather sticky sweetness in the orchestral suite Mozartiana.

In no way does it detract from the success of Tchaikovsky’s Variations that the Mozart he emulates contains no turbulent emotions. In short, the Variations are far from the real Mozart. Charming, elegant, deftly written, they are equally gratifying to virtuoso cellists and to audiences. The light and airy accompaniment, which enables the cello to stand out beautifully, is for 18th-century forces: double winds, two horns and strings.

Tchaikovsky composed the work in 1876 (shortly before beginning his Fourth Symphony) for a cellist and fellow professor at the Moscow Conservatorium, Wilhelm Fitzenhagen. Fitzenhagen had requested a concerto-like piece for his recital tours, so it was natural that Tchaikovsky first completed the Variations in a scoring for cello and piano. Before orchestrating it he gave the music to Fitzenhagen, who made changes in the solo part, in places pasting his own versions over Tchaikovsky’s. The first performance was of the orchestral version, in November 1877.

Tchaikovsky couldn’t attend since he had left Russia to recover from his disastrous marriage. Fitzenhagen retained the score, and it was he who passed it on to the publisher, Jurgenson. The cello and piano version was the first to appear in print, in autumn 1878, with substantial alterations which Fitzenhagen claimed were authorised but about which Tchaikovsky complained somewhat bitterly.

But by the time Jurgenson came to publish the Rococo Variations in orchestral form, ten years had elapsed, during which Fitzenhagen had performed the work successfully both inside and outside Russia, and it had entered the repertoire. When Fitzenhagen’s pupil, Anatoly Brandukov, asked Tchaikovsky what he was going to do about Jurgenson’s publication of the Fitzenhagen version, the composer replied, ‘The devil take it! Let it stand as it is!’

The theme, which determines the character of the Variations, is Tchaikovsky’s own. The soloist plays it after a brief introduction in which the orchestra anticipates the later breaking of the theme into fragments by attempting little phrases from it. The theme itself has an orchestral postlude, with a final question from the cello. This postlude, increasingly varied, rounds off most of the Variations. The first two of these are fairly closely based on the theme, which the cello decorates with a dance in triplets, then discusses with the orchestra. The soloist emerges in full limelight in the virtuosic second variation. This is followed by a leisurely slow waltz, largely in the hands of the soloist. This variation, number three, is the expressive heart of the work.

In Variation IV, Tchaikovsky gives the theme a different rhythm, and incorporates some bravura flourishes.

In the fifth variation, the flute has the theme and the cello accompanies with a long chain of trills. The cello solo has its most substantial cadenza at the end of this variation, which leads into the soulful slow variation, number six. This minor-key version of the theme is heard over plucked strings. It was this variation that, without fail, drew stormy applause on Fitzenhagen’s recital tours.

The final variation begins with the solo part establishing its own particular rhythmic interpretation of the theme, a delightful way of upping the activity, which continues into the coda.

David Garrett © 2002

First Performance:

30 November 1877. Nikolai Rubinstein, conductor; Wilhelm Fitzenhagen, soloist.

First WASO Performance:

1 August 1961. Karel Ančerl, conductor; John Kennedy, soloist.

Most Recent WASO Performance:

5 and 6 October 2018. Ludovic Morlot, conductor; Gautier Capuçon, soloist.

Instrumentation:

solo cello, two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, strings.