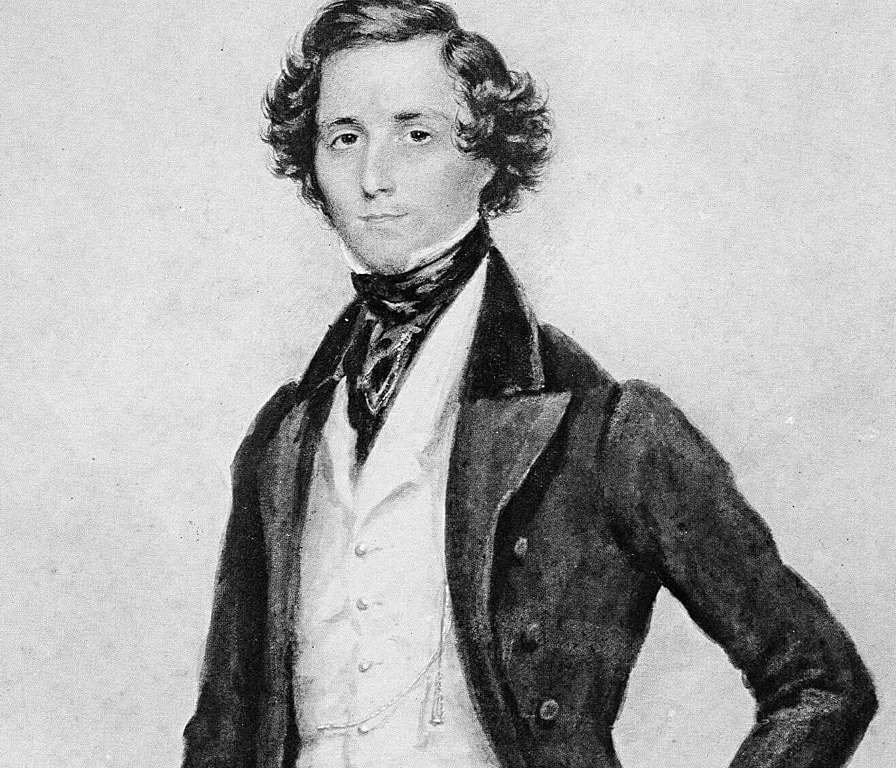

Felix Mendelssohn

(1809-1847)

Symphony No.4 in A, Op.90 Italian

Allegro vivace

Andante con moto

Con moto moderato

Saltarello (Presto)

For once a subtitle seems apt: Mendelssohn’s Italian Symphony expresses a northern European’s love of the sun-drenched south. ‘Blue sky in A major’, it has been called. The ideas for it came to Mendelssohn as he spent the winter of 1830-31 in Italy and he wrote to his parents about the symphony, that Naples ‘must play a part in it’. Indeed, it did, in the leaping dance of the Saltarello finale. Mendelssohn was in his early twenties, and in this symphony ‘there stands the eager youth who looks out with bright eyes upon the world, and, behold, all is very good’ (Ernest Walker).

Fresh and youthful, this symphony is at the same time one of Mendelssohn’s supreme achievements. He himself considered it ‘the most mature thing I have ever done’. For some reason, he was dissatisfied with it, and always intended to revise it. He never got around to doing so, and it was published only after his death. Mendelssohn had submitted the work in response to a request from the London Philharmonic Society for ‘a symphony, an overture, and a vocal piece’ (along with the concert aria Infelice, the overture The Hebrides and perhaps the Trumpet Overture). The Italian Symphony was performed in a concert of the Society in London, in which Mendelssohn also played Mozart’s D minor Piano Concerto K466, on 13 May 1833.

Mendelssohn’s anxiety about his symphonies had a lot to do with his sense of responsibility imposed by what Beethoven had done. An energetic symphony in A major was bound to put listeners in mind of Beethoven’s Seventh, and the processional character of Mendelssohn’s second movement inevitably recalls the same movement in Beethoven’s symphony. Perhaps Mendelssohn was also bothered by the challenge which faces interpreters of his Italian Symphony: how to avoid making three of the four movements sound like a moto perpetuo. Posterity considers that Mendelssohn should have remained satisfied with a masterpiece in which, far from being a pale reflection of Beethoven, he was entirely himself in the lightness of touch, the polished elegance of scoring, and the sureness of form which mark every movement of the Italian Symphony. Mendelssohn sometimes spoke convincingly of weightier things, but it is no accident that along with the Violin Concerto, the Midsummer Night’s Dream music, several overtures and the Octet for Strings, the Italian Symphony is among those works of his which have never gone out of fashion.

The opening of the symphony, like much of what follows, is notable for its brilliant and imaginative scoring. Here the bounding theme for the violins is presented to the accompaniment of repeated chords for the woodwinds, which at least doubles its effect of almost breathless energy. The second subject is a rocking figure for clarinets and bassoons which, as musicologist Donald Tovey says, is obviously in no hurry. The development soon presents a fugato on a wholly new theme, then the two main subjects are elaborately worked out and the recapitulation is approached through a long crescendo beginning under a long-held A for the first oboe – another memorably original idea.

The second movement may have been suggested by a religious procession Mendelssohn is known to have seen in Naples (though Moscheles claimed that it was based on a Czech pilgrims’ song). It begins with plainchant-like intonation, then the ‘marching’ starts in the cellos and basses, over which the cantus firmus is sounded by oboes, bassoons and violas.

Although not called a minuet and trio, this is in effect what the third movement is. There is little suggestion of the dance in this graceful music, which is more like a song without words, and the trio, with its solemn horns and bassoons, sounds a deeply Romantic, poetic note. Pedants point out that one of the rhythms of the movement Mendelssohn calls Saltarello is that of the even more furious Tarantella. The energy here is even more irresistible than in the first movement.

Mendelssohn said this symphony was composed at one of the bitterest moments of his life, when he was most troubled by his hypercritical attitude towards his own music. It is good to be reminded of this artistic struggle by a ‘driven’ personality, because his art so transcends the struggle that we can hardly guess that it ever existed.

Abridged from a note by David Garrett © 2003

First performance: 13 May 1833, London. Composer conducting.

First WASO performance: 14 June 1938. E.J. Roberts, conductor.

Most recent WASO performance: 21-22 June 2019. Asher Fisch, conductor.

Instrumentation: two each of flutes, oboes, clarinets and bassoons; two horns, two trumpets; timpani and strings.