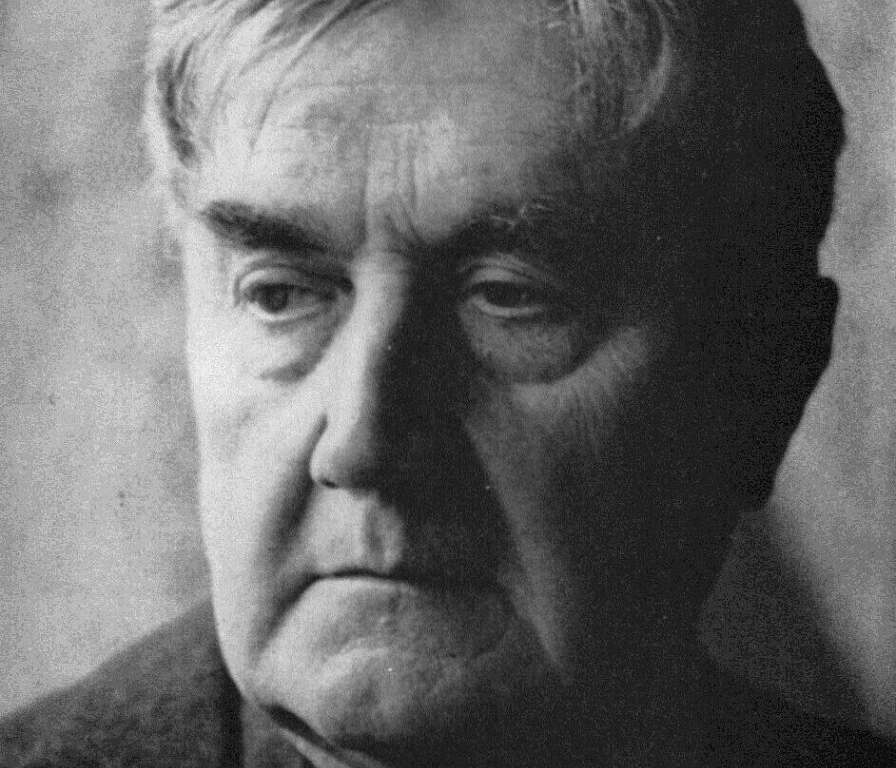

Ralph Vaughan Williams

(1872–1958)

Symphony No.5 in D Major

Preludio (Moderato)

Scherzo (Presto)

Romanza (Lento)

Passacaglia (Moderato)

Vaughan Williams’ Fifth Symphony was premiered in June 1943, six months after Churchill’s famous declaration of the ‘end of the beginning’ of the Second World War. Conflict and violence had characterised the composer’s Fourth Symphony (1935), but in this Symphony, Vaughan Williams chose to create a work of sublime tranquility and moral reassurance.

Much of the material derives from music for a projected opera of Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress. It may be true that, as the composer got on in years, he worried that this operatic project would not see the light of day, so he used some of its elements in the new Symphony. But that is a rather prosaic way of considering this exultant and musically unified work. It’s better to think of the Fifth as imbued with the character and aesthetic of The Pilgrim’s Progress, so that it represents, in Wilfrid Mellers’ words, a ‘musical quintessence’ of the book.

The Pilgrim’s Progress was a story that worked powerfully on Vaughan Williams’ imagination. Above all, the book provided him with a vision of the heavenly Ideal. A ‘cheerful agnostic’, he understood the promise of heaven and its importance for individuals and for society. Perhaps this heaven can be read more rightly as ‘utopia’, its defining character: peacefulness. Musicologist Frank Howes observed that in this Symphony, Vaughan Williams not only reflected upon a world after the War, in which there is an ‘absence of armed conflict’, but aspired to essay a higher condition of ‘peace, ultimate and fundamental’. This peaceful state is attained only after a considerable quest.

While thankfully the Symphony doesn’t put us through a litany of trials such as ‘Pilgrim’ goes through, we nevertheless gain a sense of a life’s journey through different emotional experiences. The Symphony adopts a relatively formal Classical symphonic structure, so we should avoid ascribing to it an excessively programmatic or narrative reading. However, some of the Symphony’s music appears also in Vaughan Williams’ other versions of the Pilgrim’s Progress story, in particular a radio play from 1942 and an opera (more like a dramatic oratorio) performed in 1951. Some observation of the links between the Symphony and other Pilgrim’s Progress material can inform an appreciation of the music.

The Symphony opens with an evocation of blissful, unsullied nature. Human or perhaps sinister influence intrudes, with thematic material adapted from music associated with Beelzebub in the opera. The sinister presence comes forward more in the second movement, where the scurrying, ethereal music is like that with which Vaughan Williams describes Pilgrim’s fight with ‘hobgoblins’ in the opera.

The third movement is entitled Romanza, but even here the idyllic mood (material similar to the opera’s Act I, Scene ii, ‘The House Beautiful’) is contrasted with music of agitation (Act I, Scene i’s ‘Save me, Lord! My burden is greater than I can bear’). The final movement is dominated by a glorious passacaglia on a hymnlike theme, rising to a great D major climax. But, this is not the Symphony’s end. An epilogue shares material with the scene in the opera where Pilgrim passes over the River of Death, entering humbly but triumphantly into Paradise.

These instances illustrate not so much a narrative underpinning, but a philosophical one for the Symphony: the pursuit of goodness and justice faces continual challenge from darker forces. In seeing evidence of Pilgrim’s Progress in the work, we understand its character as one of benediction. In the contest of good and evil, Vaughan Williams offers us gentle encouragement to maintain our resolve and persistence towards attaining the final goal – peace.

The music’s structure reflects this philosophical purpose. The Classical structure is subjected to such richly imaginative and intuitive remodeling we can barely recognise it. For the most part, the Symphony proceeds by means of contrasts rather than traditional ‘argument’ or ‘conflict’. Artful combination of ancient modality and pentatonic harmony with contemporary tonality creates an extended, harmonically luscious soundworld. It’s only in the final movement that D major unequivocally asserts itself, its triumph so emphatic that Mellers describes the key as representing ‘human fulfilment’.

The feeling at the end of this work is one of absolution, from which, it is to be hoped, we gain the resolve to continue our pursuit of the just cause or to seek out the path of goodness.

James Koehne © 2004

First performance: 24 June 1943, London, composer conducting.

First WASO performance: 23-24 May 1952; Rudolf Pekárek, conductor.

Most recent WASO performance: 13-14 October 2017; Douglas Boyd, conductor.

Instrumentation: two flutes, oboe, cor anglais, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, three trombones, timpani, strings.