WASO's The Lark Ascending & Mozart's Masterpieces

WASO ON TOUR

Saturday 8 February 2025, 7.30pm

Mandurah Performing Arts Centre

West Australian Symphony Orchestra respectfully acknowledges the Traditional Custodians and Elders of Country throughout Western Australia, and the Bindjareb Noongar people on whose lands we work and share music.

How to use your Digital Program

The Lark Ascending and Mozart's Masterpieces

Wolfgang Amadeus MOZART Don Giovanni: Overture (6 mins)

Ralph VAUGHAN WILLIAMS The Lark Ascending (16 mins)

Benjamin BRITTEN Simple Symphony (16 mins)

Boisterous Bourrée

Playful Pizzicato

Sentimental Sarabande

Frolicsome Finale

Interval (20 mins)

Wolfgang Amadeus MOZART Symphony No.40 (35 mins)

Molto allegro

Andante

Menuetto (Allegretto) – Trio – Menuetto

Allegro assai

Laurence Jackson Director/Violin

Presented by Mandurah Performing Arts Centre.

WASO On Stage

About the Artists

About the Music

About the Music

About the Music

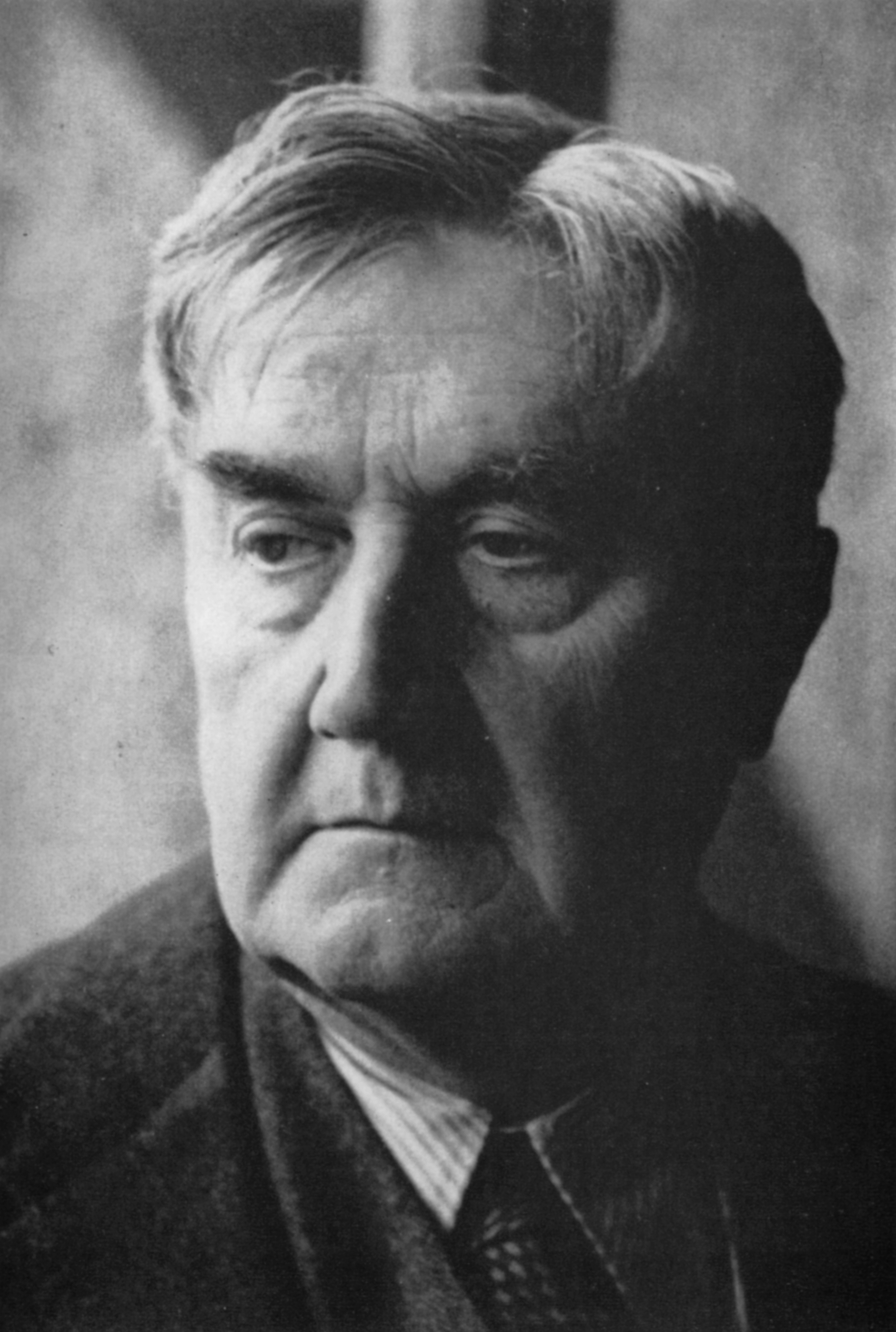

Benjamin Britten

(1913-1976)

Simple Symphony, Op.4

Boisterous Bourrée

Playful Pizzicato

Sentimental Sarabande

Frolicsome Finale

It is usually left to devotees of the music of a major composer to resurrect juvenilia, the ideas of a highly musical child. Britten, however, performed that service himself with his Simple Symphony. This was assembled in 1934, when he was 21, from works he had written before he was 12. The dilemma facing the composer was how far to ‘touch up’ his simple, innocent ideas. Britten’s piece keeps much of the fresh charm of unsophisticated music, but he has not entirely resisted the temptation to introduce a more mature cleverness in putting his original piano pieces and songs side by side to form symmetrical, classically modelled structures.

As is often the case in Britten’s music, the Simple Symphony is the result of a practical challenge the composer had set himself: how to write ingenious and satisfying textures for strings without exceeding the technical capacities of quite modest amateur players. The symphony is simple in more ways than one. To be played either by a string quartet or by a string orchestra, it already displays the deep understanding of the string medium which Britten (an amateur viola player himself) was to reveal at full stretch in 1937’s Variations on a Theme of Frank Bridge. Britten later wrote:

'I am attracted by many features of the strings. For instance, the possibilities of elaborate divisi – the effect of many voices of the same kind. There is also the infinite variety of colour – the use of mutes, pizzicato, harmonics and so forth. Then again, there is the great dexterity in technique of string players. Generally speaking, I like to think of the small combinations of players, and I deplore the tendency of present-day audiences to expect only the luscious ‘tutti’ effect from an orchestra.'

Of course, not all the available techniques are exploited in the Simple Symphony, but it is remarkable how many are. There is perhaps an element of tongue-in-cheek as Britten shows how classical musical structures are built out of the simplest musical ideas. There is cunning in this innocence. The dance form of the Boisterous Bourrée contains some elementary counterpoint exercises, and the trio of the Playful Pizzicato has some witty silent bars in its tune. The Sentimental Sarabande has been described as ‘bogus-Baroque’, but Britten’s attitude to its expressiveness is revealed in the adjective of his alliterative title. The excitement of the Frolicsome Finale is built up from a theme which, as Peter Evans has remarked, a cinema pianist would have cherished.

David Garrett

© Symphony Australia

First performance: 6 March 1934. Norwich, Benjamin Britten, conductor.

First WASO performance: 27 August 1949. Henry Krisps, conductor.

Most recent WASO performance: 3 March 2019. Laurence Jackson, director.

Instrumentation: Strings

Glossary

Divisi – literally ‘divided’; used when a string group in the orchestra (e.g. the First Violins or the Cellos) is temporarily split into two or more smaller groups, playing different parts.

Harmonics – high pure flute-like sounds. Normally, string players press down firmly on the string with the fingers of the left hand to select the pitch of the note; harmonics are produced by lightly touching the string.

Pizzicato – plucking, rather than bowing, the strings.

Tutti – all the instruments of the orchestra playing at the same time.

About the Music

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

(1756 – 1791)

Symphony No.40 in G minor, K550

Molto allegro

Andante

Menuetto (Allegretto) – Trio – Menuetto

Allegro assai

Producing over 50 symphonies (the official number 41 notwithstanding) in the space of 23 years, Mozart can truly be said to have enjoyed a ‘symphonic career’, much as did his older friend Joseph Haydn (100 symphonies in 38 years). And as symphonic careers go, it was, like Haydn’s, successful from first to last. Mozart composed his Symphony No.1 – perhaps with a little help from his sister and father – in the London suburb of Chelsea in summer 1764. Generically and stylistically, it dots all the ‘i’s and crosses the ‘t’s, almost as convincingly as do the symphonies of one of his London mentors, Johann Christian Bach, works indeed said to have ‘influenced’ the eight-year-old’s first attempt. Between the ages of 15 and 18, he produced all of what now count as his ‘middle period’ symphonies (Numbers 14-30, and at least 5 unnumbered).

After relocating from Salzburg to Vienna in 1781, however, piano concertos took over as Mozart’s preferred orchestral vehicle, better for charming fickle metropolitan audiences than the more esoteric symphony. New symphonies were not entirely absent from his Vienna concerts, but all of them from these years were, in the first instance, out-of-town commissions: No.35 for the Haffner family in Salzburg in 1782; No.36 and the so-called No.37 (most of it actually by Michael Haydn) for a concert in Linz in 1783; and No.38 for Prague in 1787, during the season there of his opera The Marriage of Figaro.

On 24 February 1788, only months before starting on the next three symphonies, he finished his Piano Concerto No.26 (‘Coronation’). Then in May, the imperial theatre in Vienna unveiled for hometown audiences his latest Italian opera, Don Giovanni (or the Libertine Punished), premiered in Prague the previous October. The tepid reception it received perhaps explains why Mozart devoted much of the sultry Viennese summer that year to composing three new symphonies, Numbers 39-41, works that, like their immediate predecessors, were unlikely to appeal greatly to the Viennese. By then, Austria was at war with Ottoman Turkey. Accordingly, most of his patrons were also feeling the economic pinch, and Mozart’s plans to give another concert series, at which the new symphonies might have been performed, came to nothing. However, it may well have been with one eye to possible publication and performances in England, France and Germany that he completed the trilogy in quick succession between June and August.

Minor keys are natural phenomena in the music of Beethoven. In Mozart’s overwhelmingly sunny output, however, they seem like unseasonal intrusions, requiring some explanation from outside of the composer’s usual circumstances. Yet if minor keys signify depression or fatalism, causes are easy enough to find leading up to the completion of the Symphony No.40 on 25 July 1788. Not only did Don Giovanni flop, but tragically, at the end of June, Mozart’s six-month-old daughter Theresia died. Perhaps this explains why the G minor symphony’s first movement is saturated with Mozart’s most unusual and haunting theme.

The other three movements are far less familiar to most people, and so can still surprise. After Mozart’s death, Haydn quoted a phrase from the luminous second movement in his oratorio The Seasons, memorialising his young friend. Since the Andante is also the symphony’s only major-key movement, the Viennese had by then come to prefer it too. What the Romantics thought of as the high-minded angst of minor keys was all too often anathema to Viennese audiences, as Beethoven later discovered. But at least they had more staying power than the average audience today. When played with all its repeats, as Mozart intended (but which most conductors do not bother with today), it is almost twice as long as the opening movement.

The third movement, a minuet in G minor again, is not a well-balanced, copybook example of the dance. This one is energetic and eventful, with dissonant notes and syncopated rhythms – as unusual, in its small way, as the opening movement. The fourth movement is an orchestral tour de force, designed by Mozart to sweep his audience along in a state of increasing nervous excitement. Its inexorable forward motion is interrupted only by the weirdness of a couple of audibly disconcerting moments, when Mozart perversely avoids any clear sense of key for rather longer than is comfortable.

Adapted from an annotation by Graeme Skinner © 2013

First performance: Mozart entered the work into his catalogue on 25 July 1788, however the date and circumstances of the first performance is not known.

First WASO performance: 3 July 1943. Lionel Dawson, conductor.

Most recent WASO performance: 16 March 2019. Asher Fisch, conductor.

Instrumentation: flute, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, strings.

Glossary

Major/minor – types of key. Very generally, music in major keys tends to sound brighter (e.g. Twinkle, twinkle little star), whereas minor keys have a more sombre, melancholy feel (Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata).

Minuet – stately dance in triple time, which became popular in France in the 17th and 18th centuries. In a symphonic context, the term is also used to refer to a dance-like piece or movement in moderately fast triple time.

Oratorio – a substantial work for singers and orchestra, often based on a religious text.

About WASO

Your Concert Experience

Meet the Musician

Jeremy Garside

Cello

What’s your earliest memory of playing music?

My earliest musical memory is of my sister playing the piano. I wanted to learn because she did, and I would flip through her beginner piano books, trying to play from them. This sparked my desire to take piano lessons, and I soon started as well.

What inspired you to play the cello?

I was exposed to various instruments at Davallia, my primary school. In Year 3, I had the opportunity to learn the violin, but I found I didn’t like the sound of it. I was drawn to the cello instead and, though I had to wait a year, I seized the chance to start learning it.

Is there anything special about your instrument?

My cello is a modern instrument, made in 2015 by Pietro Contu, a luthier based in Bruchsal, Germany. My teacher, Suzie, strongly advised me to upgrade my cello and find an instrument that could support my future growth. Following her recommendation, I visited Pietro, tested several cellos, and ultimately chose the one I now play – and love. It was also my first trip to Europe, made even more memorable because I got to see my sister’s ballet performance in Mannheim.

Do you have a favourite genre or style of music to play?

Classical music, without a doubt. I'm particularly drawn to the symphonic repertoire, but I have a passion for chamber music as well. The two complement each other. Now that I'm settled back in Perth for the foreseeable future, I’m excited to delve into more chamber music projects.

What’s the best advice you’ve received during your career?

My teacher, Suzie, had a mantra that has always resonated with me: 'Cool head, warm heart.' I think it’s good advice, both for playing music and navigating life in general!

Bringing Music to Every Corner of WA

Duet Partnerships

Our Supporters

Circles of Support

Trusts and Foundations